There are far more Zhijé texts among the pre-1200 CE Matho fragments than anyone would have expected. To my mind this signals that Zhijé was more influential in those days than we have ever imagined. Among those Zhijé fragments, I managed to ferret out four that belong to a particular Middle Zhijé lineage that descended from Rma.* Just to remind yourself what the Middle Zhijé lineages are, take only one minute to look at the chart that is today’s frontispiece.

(*Matho fragments v123, v249, v263 & v285; notes in Appendix B, below.)

Geshé Deyu (དགེ་བཤེས་ལྡེའུ་), author of the root verses (in circa 1180’s) later on made use of in a few so-called Deyu histories, did belong to an Intermediate lineage, but not to the Rma. No, he was of the So lineage. And long ago we blogged about newly emerging early Zhijé texts found at Drametsé in eastern Bhutan. The Rma lineage dominates one of these Drametsé manuscript sets, and I think it a matter of wonder and fascination that our best primary sources on the Rma lineage come from places so far apart.* Today we will pay attention to the four Rma texts of Matho, all related closely to one Rma lineage holder in particular, one named Khugom Joga (ཁུ་སྒོམ་ཇོ་དགའ་).

(*By 'primary' I just mean pre-Mongol-era. Checking distances on the internet, we could get from one to the other via northern India by driving around two thousand miles in a minimum 60-hour nonstop road trip; or, if you prefer, a 5- or 6-hour flight. It would be like traveling from Boston to San Francisco. Drametsé Thorbu no. 041, found in the British Library’s Endangered Languages project, includes previously unavailable histories of all three of the major Middle Transmission lineages, and wouldn’t you know there is even a Skam history in the Matho (v177) that we will need to blog about another time, not to mention a previously unheard of Zhijé history in the holdings of the Vatican Apostolic Library.)

To make the chronological problem quite simple, these Rma texts share enough information in their colophons for us to conclude that Rma (b. 1054) taught Ganden (Dga'-ldan), who in turn taught Khugom. Khugom makes reference to himself as the one who jotted down the notes, and in more than one case his words were written down by his own disciple Mingyur (Mi-'gyur) so we can at least be sure enough that this happened in middle decades of the 12th century. For most of the very little we have until this moment known about Khugom and his position within the sub-lineages, just look at these two paragraphs from the Blue Annals:

“Again Khu-sgom Jo-dga’, who dwelt in the valley of Klu-mda’-tshe, had numerous disciples. He taught it to Rgyal-ba Dkon-mchog-skyabs of Stod-lung Gzhong-pa Steng. The latter preached the doctrine to Rog Shes-rab-’od.

“Shes-rab-’od obtained at that place the understanding of the Mahāmudrā. Again Zhang-brtsun Rgyal-ba-bkra-shis taught it to ’Chus-pa Dar-brtson. The latter taught it to ’Chus-pa Brtson-seng. The latter taught it to Rog Shes-rab-’od. Now there have been two Lineages in the school of Rma: that of the Word, and that of the Meaning. The Guidance of the Meaning (don khrid) included 16 lag khrid or practical guides. The Lineage of the Word contained the ‘giving life to the thought of Enlightenment’ (cittotpāda), a summary (stong-thun), a miscellany (kha-’thor), that “which hits the mouth and the nose” (khar phog snar phog), meaning criticism of the point of view of others, and the “extensive” (exposition, mthar-rgyas). [This ends] the Chapter on the school of Rma.”

(*I really must point out that I once believed the “which hits the mouth and nose” with its added explanation “meaning criticism of the point of view of others,” was dubious, since an alternative reading gives us ear (rna) in place of nose (sna), and this seemed to make so much better sense when it is a subject of an esoteric contemplative tradition, passed from mouth to ear. But now I am not so sure, since one lexicon defines the entire phrase to mean some sort of harsh and unfiltered speech. It appears this phrase is exclusively used in Zhijé contexts, and so far I have not seen a Zhijé explanation of it. I think it likely means ‘occasional utterance,’ ‘spontaneous expression’ or the like. There was no monastic debating ground in the remotest corners of their minds, no philosophical positions requiring rational refutation. We are about as far as we could possibly be from Sangpu Neutog [གསང་ཕུ་ནེའུ་ཐོག་].)

Key reference points

See these earlier Tibeto-logic blogs for further bibliographical pointers:

“New Padampa Manuscripts” (July 2, 2016). This tells of the manuscript discoveries by Karma Phuntsok at Drametsé Monastery in Eastern Bhutan that have revolutionized the study of early Zhijé and Cutting traditions.

“Recovered Connections 2 - Interdependent Emergence of Tibetan Buddhist Schools” (April 30, 2024). This was an attempt to look more deeply into the content of the Matho fragments as a whole.

“Padampa in the Vatican,” Tibeto-logic (March 22, 2024).

1. Access to the Matho fragments (W1BL9):

2. The Matho fragment handlist by myself:

https://sites.google.com/site/tiblical/matho-fragments-handlist

✪3. The Matho fragment handlist by Bruno Laine:

4. “Story of the Matho Fragments”:

Drepung Catalog: Dpal-brtsegs Bod-yig Dpe-rnying Zhib-’jug-khang, ’Bras-spungs Dgon-du Bzhugs-su Gsol-ba’i Dpe-rnying Dkar-chag, Mi-rigs Dpe-skrun-khang (Beijing 2004), in 2 volumes (pagination continuous). For further reference, look here. On pp. 710-712 and 808 are several titles, some quite lengthy, that are remarkably close in their titles to those mentioned in the Blue Annals passage, so chances are very high that texts parallel to the Matho are preserved today in Drepung Monastery’s Sixteen Arhat Chapel library (see Ducher’s essay). These parallels would allow us to flesh out the contexts and contents of these fragments. Most obvious to remark about are Stong-thun texts that include one by Zhang Gandenpa (Zhang Dga'-ldan-pa), as well as Rma lineage texts transmitted to one ’Og-ka [~’Ol-ka] Skya-rgyal by one Phug-ra-ba. These last-mentioned names are liable to intrigue us by their very obscurity.

Cecile Ducher, “Goldmine of Knowledge: The Collections of the Gnas bcu lha khang in ’Bras spungs Library,” Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines, no. 55 (July 2020), pp. 121-139. Available without cost online, this has golden information on the Drepung Sixteen Arhats Chapel’s library and its history.

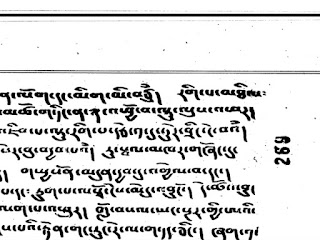

Gendun Chomphel and George Roerich, trs., The Blue Annals [of ’Gos Lo-tsā-ba Gzhon-nu-dpal, 1392-1481], Motilal Banarsidass (Delhi 1976), p. 876. The passage supplied above was based on this translation, while changing the transcriptions of proper names to ordinary Wylie, with a few minor changes in the interest of clarity. The Tibetan looks kind of like this:

yang khu sgom jo dgas klu mda' tshe lung du bzhugs nas gdul bya mang du bskyangs | des stod lungs zhong pa steng gi rgyal ba dkon mchog skyabs la gsungs | des rog shes rab 'od la gsungs | shes rab 'od kyis phyag rgya chen po'i rtogs pa der shar | yang zhang btsun rgyal ba bkra shis kyis 'chus pa dar brtson la bshad | des 'chus pa brtson seng la bshad | des rog shes rab 'od la gsungs so | | de la rma'i chos skor ni chig brgyud [~tshig brgyud] dang don brgyud gnyis las | don khrid ni lag khrid bcu drug [/] chig brgyud ni sems bskyed dang stong thun dang kha 'thor dang khar phog snar phog [~khar phog rnar phog] dang mthar rgyas rnams so | | rma lugs kyi skabs so | |

Sarah Harding, “Distilled Elixir: A Unified Collection of the Guidebooks of the Early, Middle, and Later Pacification.” There is also the book. If you do have access to Sarah’s translation of Jamgön Kongtrul, Zhije, Snow Lion (Boulder 2019), I recommend reading pages 419 through 430 for a breathtaking aerial view of the Rma School’s meditation precepts.

Rog Sherab Ö (རོག་བནྡེ་ཤེས་རབ་འོད་, 1166-1244 CE), History of the School of Rma (no front title, but entitled in the colophon as Rma-lugs-kyi Lo-rgyus), contained in: Drametse Thorbu 041, part of the British Library's Endangered Archives Project. A manuscript in 4 folios [ends at p. 66a following the numbers of the scans]. This entire text has been attached in transcription below, in Appendix A. A table of contents of the whole volume that contains it, Drametse Thorbu 041, is in Appendix C.

§ § §

Appendix A: Transcription of The History of the School of Rma

Note: I have supplied rough translations and summaries of the later parts containing material directly related to Khugom. No author’s colophon as such appears here, even if there is an ending that might be wrongly taken as a colophon. I believe that, just like the brief historical texts on the So and Skam schools in this collection, it was made by Rog Sherab Ö, who is mentioned in the body of the text.

11. No front title. Rma lugs kyi lo rgyus [title from colophon]. 4 fols. [ends p. 66a of the scans]. This is the 11th title in the set that takes up all of Drametse Thorbu 041 (for Table of Contents, see Appendix C). I think its authorship may be securely attributed to Rog Sherab Ö.

[1r] na mo 'ghu ru / 'jam dpal smra ba'i seng ges dpal 'bir rgya ba / des a rgya de ba la / des rje dam pa rgya gar la'o //

[Brief biographical sketch on Padampa, followed by the biography of Rma]

de la dam pa'i lor rgyus ni / skye ba bdun du pan 'gri ta'i lus tsag mar bzhes pa yin ste / skye ba 'di la / yul lho phyogs rtsa ra sing nga zhes bya ba'i grong khyer du / yab bram ze nor bu len pa / yum bram ze mo spos sbyor ba'i rig pa byed can / de la sras gsum yod pa'i bar pa dam pa nyid lags /

de yang lo lnga lon nas 'bri klog la sbyangs / lo bcu' gsum la / 'bri ka ma la'i rtsug lag khang du phal chen pa'i sde pa la rab tu byung / 'du ba la legs par sbyangs //

de nas rnal 'byor pho mo lnga bcu rtsa bzhi'i bla ma rten / gzhung gdams pa ma lus pa gsan bsgrub pa mthar phyung nas / bod du 'gro ba'i don la lan gsum byon skad //

lan dang po de bal po la byon nas / byang lam 'grims / zhang gzhung gling ka ba dang / khra tshang 'brug bla la rjun 'phrul gyi gdams pa gnang /

de nas rgya nag ri bo rtse lnga la 'phags pa 'jam dpal la chos gsan / slar rgya gar du byon skad //

lar bar pa de mon sha 'ug las sgo thon ste / dmyal du byon / myal gyi snang gror g.yog po lo gsum byas /

de nas yar stod du byon / khu lo dang 'byal bar bzhed pa la / khu dam nyams su 'dug pas log nas / skyer rnang byon no //

[Padampa and Rma meet]

de'i dus su bla ma rma dang 'byal ste / de yang bla ma rma de dge' ba'i bshes gnyen chen po yin pa la / snyung nad yun rings kyis btab nas / [1v] ma drag pa la / dus na ma cig phyir byon snying 'dod pa la / 'khor kun gyis brten nas byon / der skyer sna'i phyir rol na / pho mo cig gi steng na a rtsa ra cig 'dug nas / shin tu mos pa cig byung ste / zhag 'ga chos ston grang byin brlabs zhu byas pas / skye ba mang po nas las 'brel yod pa yin pas de rtsug byas pas chog gsung nas / nang du gshegs / lam rgyus med par brang khang ngo shes byung pas yid ches / zhag bcwa brgyad gdams pa zhus / chos ston grangs pas / rdo ha [~do ha] la rten pa'i phyag rgya chen po'i rtsa ba'i ngo sprod gnas / shin tu nges shes skyes der dam pa da 'gro gsung pa la / da rung bzhugs par zhus pas ma snang / gzims pa'i sog ma ma zhar ba dang / spyod lam gyis ngom mtshar skyes nas / chags phyir 'khrid par zhus pas kyang / ma snang /

'on gyang phyir 'brengs pas skyon du byung / bskyon gyang 'brengs pas rog pa rtsar byon / bla ma gnyan ston gyi dben rtsar bzhud / rmas dge' rar gzims / yang nang par skyon ya phyir 'brengs / gad pa stengs su phyin pas / da sdod phrag de 'ong pas log gsung / gsung kyang phyir 'brengs pas / bya sar byon / bla mas nag po tshangs su gzims pas / g.yog pos phyir ston / nub mo phyugs rar gzims / nang par nam phabs gter gter la che long cig blangs nas / gsol / de nas bya sa'i gru la sgrol byas pas / ma sdub / a tsa ra la gru mi dgos gsung nas / pha tse'i steng du bzhugs nas bzhud / rmas bya sa'i gru la byon / bsam yas su or brgyad dkon mchog dbang gi can du gzims /

de nas rma la la byon [2r] klag du rtsun ma'i gnas su bzhugs / de'i tshe bla ma rma la khyod rang log / sang sna sa dgun 'phan yul du shog gsung // der rmas log nas yul du byon / 'khor dang yo byed thams cad spangs / slar 'phan yul du byon nas tshig rgyud rnams tshar bar zhus //

de nas bla ma rma ni / nyams rnam pa dang rtsa ba bral / blo dang chos zad / lta ba thag chod nas / skong po brag gsum rdzong lo dgu' bzhugs /

de'i dus su dge' bshes shud pu lo tsha ba dang / gang par gshin gyis gdams pa zhus / de nas dags po rdzong khar bzhugs nas bsgom cheb mang du brteb //

de nas 'jal gyi kyi tshang du lo gsum bzhugs / de'i dus su zhang ston bon mo dpal dang / zhal ston bkra shis 'bar gyis zhus / dus de yan chad du sems bskyed lam khyer las ma gnang ngo // • //

[The history of Zhang Gandenpa]

de nas zhang dga' ldan pa'i lor rgyus ni / dang po phu dang don 'gar kyi mtshams pa yin pa la / yab ni / dmyal rtag rtse dpar mo'i phyir byon pas 'das / me sring chung pa gnyis lus / ka cha med nas lug lo bzhi lnga rtsam btsas / de nas dad pa skyes ste / zhing gsum yod pas cig brtsongs nas / stod lungs su bla ma skor gyi spyan sngar byon / dbang la gsum zhus / gshin rje dang phag mo'i chos zhus / lo sum bcu rtsa bdun tshun chod bzhugs / de rtsa na bla ma so chung pa / bla ma skor la chos zhur byon pa dang / 'byal nas kyang chos zhus / ngo bo rang bzhin mtshan gsum gyi gdams pa gnang / de nas yul du byon nas / zhing gcig la chu 'chu'i yod tsa na / btsun ma zhar ma / khengs mo cig na re / nga grogs po cig la grogs su bcol zer / [2v] de'i bar du chos gtam byas pas / zhang gis ji skad gsungs pa la de rnams yin / dri ma yin zer sun ston no //

'o na btsun ma'i slob dpon de lta bu gang na yod byas pas / bla ma rma yin zer ngas gdams pa zhus na gnas sam byas pas / gnang yod zer ro //

[So he asked, Where might I find such a teacher? and he replied "I am Lama Rma.” “If I ask for precepts may I remain here?” “I permit it.”]

cig car 'byor khyim du skyal nas / phye dang rgyags khyer nas / zhang 'gar byung pa'i grogs po dang 'grogs nas byon ste / yar lungs su ris pas / bla ma byar du bzhud zer / der btsun ma mo la 'gro rogs zhus pas / btsun ma na re / nga la skyon du 'ong / khyed rang bzhud la / bla ma rgya gar gyi gdams pa rtsa ba thun bcud zhud gyis zer ro //

der phyin tsa na / byon chang mang po yang 'dug / thams cad 'tshogs nas chos gang zhu'i gros byed kyi 'dug pa la / bla ma'i zhal nas ston pa yas chos ci 'dod gsung pas / nga rgya ma rgya gar gyi rtsa ba thun bcud zhu ba lags byas pas / stong du sa spa ra gang gtab nas de 'dra yod pa su la yod / thos pa su la thos gsung nas skyon pas / skengs te / chos mi 'ong par 'dug snyam nas yi mug ge cig nyal ba ba dang / nang par tsha ba la 'bod nas phyin tsa na / khyod kyis su la thos gsung / thos pa cig dang bdog ste byas pas / jo mo skong mos bzlas nges / da khyod 'ongs kyi ting la gdams pa byed dgos gsung /

der dga' ches te rgyags kyi sbyor ba byas / bla mas thun bcud dang rtsal sbyong gi gdams pa gnang pas / gra pa gzhan rnams kyang khyod drin che bas / phyag btsal dgos par 'dug gsung /

de nas gdams pa ma lus gnang nas rgyud pa gtad pa yin gsung ngo // • //

de nas phyis bla ma gad pa stengs su ltog pas snyung pa'i tshe [3r] slob ma che dgu' 'tshogs pa dang / shud pu lo tsa ba na re / ngas rgya gar gyi khri 'do' li bya ba shes kyis / slob dpon gzims pas chog pas / skyer rnar bzhud par zhu byas pas /

bla ma'i zhal nas / dge' bshes / zla ba phyi ma'i tshes bcu gcig la nga 'ong gis / skye sna ba rnams chang mang po tshos cig / rma chang la ni dga' / to pi gzur zhu byas la 'ong cig byas pas / bu slob rnams chu ma shor /

de'i tshe zla ba phyi ma'i tshes bcu gcig la grongs pas / de'i dus su slob ma thams cad 'tshogs nas / gad pa stengs kyi 'khyams su nyal tsa na / nang par tho ras bla ma zhang gis bltas pas / thams cad bsgom kyi 'dug pas / bla ma spa sa la yi bsgom pa'i gdams pa btab nas 'dug gsung /

gzhan rnams nyam len dang bral ba cig kyang mi 'dug pas / dus der bla mas thugs la btags par byung snyam nas ngos shes skye gsung //

de nas yul du byon nas / ma rgan shi ba'i dge' rtsar zhing cig rtsong nas / tshogs 'khor byas / yang cig btsongs nas rog pa rtsar bskyeg pas / 'jug tu tsa ba tor /

de nas dbu rar btsun ma rnams kyis bshos lo gsum grangs / de nas mon khud du btsun ma rin chen sgron gyis spyan grangs / slob ma 'ga' re bskyangs / skyes bu se ra la mthar rgyas dang kha 'thor gyi gdams pa btab /

de nas dga' ldan du bzhugs nas / slob ma sngags pa'i mi chen nye tshe bskyangs pas / rgyud pa zin pa tsam ma byung skad //

[Four great sons of Gandenpa]

dus phyis bu chen bzhi byung ste / khu bsgom jo dga' / skyogs bsgom bsam gtan / dmyal ston dga' chung 'bar / rgya dar seng dang bzhi'o //

[The account of the meeting of Khugom with Gandenpa]

de la khu bsgom dang 'byal ba'i lo rgyus ni / [3v] lo sum bcu rtsa bdun la / bya sar ltad mo byon / mi thog rta thog gnyis kha chod pa la / gza' rgyu ba dang phrad nas yun rings na / ci byas kyang ma drag nas / bla ma zhang gi thad du byin brlabs zhus pas drag / des nges shes skyes ste / gdams pa zhus pas / bsgom byed dang bral ba'i don rgyud la skyes skad //

dus der ston chung dge' bsnyen la nad byung pas / khong 'khyam du 'gro ba la snying rje bar dgongs nas / ngo sprod kyi yig chung 'debs / lha rje 'jig rten 'bar gyis bshad na [~cig?] phul nas zhus pas / stong thun chu rgyu yi ger bkod / de yan chad du yi ge cig kyang med skad //

[...Prior to this it is said that the lineage had no written documentation...]

zhang gis mtha' rgyas dang / stong thun chu rgyun / kha 'thor rgya pa tsho las ma bkod skad // gzhan snyan rgyud yin no //

der rgya dar seng skyogs bsgom bsams bstan [~bsam gtan] gyis khrid byung pa la / zhag nyi shu rtsam las ma bsdad / zin ris mang du byas / khu bsgom la yang ngo sprod kyi yig chung kha yar zhus te / thams cad de'i dus su yi ger btab / de'i dus su zhu ba po'i bye brag gis / rgyas bsdus 'ga' re byung pas che chung du song / don la khyad med / rgyas go bcad nas rma'i lugs dar bar byas so //

de la khu bsgom ni bla ma'i spyan sngar yun gyang [~kyang] ring / zhabs tog kyang che / thugs la bstags pas / gdams pa gzhan pas rgyas shis / zhu thar [~zhun thar] chod pa yin skad //

[Next was Khugom. He remained especially long in the presence of the Lama and was great in his service. With this in mind the teacher granted him more extensive precepts than the others and all of his doubts* were resolved. *Note use of zhun-thar, a pre-Mongol era term with meaning of “doubt” later replaced by the-tshom.]

lan cig shel gyi nang du ri nyil nas / zangs rdo brdol bas sgrug pa la thams cad song tsa na bla ma khu na re / zangs rdo bas bla ma'i gdams ngag dga' zer nas bsdad pas / chos 'dod nges su go nas / slob ma gzhan med kyi bar du / zhag bcu bzhir / gdams pa thams cad 'phra bcad nas [4r] gnang skad do //

[Once inside the crystal [cave?] the mountain crumbled {there was a landslide?}. When a copper stone broke free he picked it up and when everyone came to have a look Lama Khu said, "The precepts are more happily found than a copper stone." As he sat there he understood there was a definite desire for Dharma, so during a time when there were no other disciples, a period of fourteen days, it is said that all the precepts were granted after he had decided the fine points.]

der gdams pa yod kyang / gsang spyod du byas nas bzhugs pa la / bla ma grongs pa'i dus su bu slob kun gyis / bla ma grongs pa'i shul du gdams pa su che zhes pa / khu bsgom che gsung //

der zhang gi slob ma rnams khu bsgom la 'phungs pa lags skad do // • //

[Zhang’s former disciples are said to have gathered there around Khugom.]

de la rje btsun rgyal pas zhus te / rje btsun de rtsang la sdog gi chags phyi na zhi byed so lugs gsan gyi bzhugs pa la / sdog gis snyan ston dga' chung 'bar la rma lugs gsan / der slob dpon gyis kyang byon /

[It was from him that Jetsun Gyelpa, i.e. Tenné, requested the teachings. It was while this Jetsun was servant of Dog in Tsang that he entered the teaching of Zhijé’s So School and Dog was receiving teachings on the Rma School from Nyantön Gachungbar. These the Teacher (Slob-dpon, i.e., Tenné) also attended.]

de nas yar mdar byon nas / khu bsgom gyi slob ma dang klong langs byas pas gdams pa khyad yod par shes nas / khu bsgom gyi spyan ngar byon / de'i dus su rje btsun rgyal pas kyang byon / rtsang pa bsdog gis zla ba gnyis bzhugs / rje btsun rgyal pas phyis lo cig bzhugs skad do //

[Then he went to the lower part of the Yarlung River Valley where, after spending time with a disciple of Khugom, he came to know that Khugom had some special precepts, so he went to his presence. At the same time Jetsun Gyelpa also arrived. Tsangpa Dog remained there for two months. It is said that Jetsun Gyelpa remained for one more year.]

de la rog gi ban dhe shes rab 'od kyis zhus te / brgyud pa gtad pa yin pas sems can la phan thogs cig gsung //

[From him, Tenné, the Bande of Rog, Sherab Ö, requested the teachings. The teacher told him, “The transmission has hereby been handed on, so be of benefit to sentient beings.”]

yang rje btsun chus pas rma'i bu chen cig la thug ste / zhang btsun rgyal ba bkra shis / sog po mdo sde / gang par gshin rje (gshein?) / khu bsgom dang bzhi la thug /

[Jetsun Chüpa met one Great Son of Rma and then he met these four: Zhangtsun Gyelwa Tashi, Sogpo Dodé, Gangpar Shinjé, and Khugom.]

des kyang rog gi ban dhe sher rab 'od [~shes rab 'od] la gnang ngo //

[It was by him (by Tenné), too, that the teachings were granted to the Bande of Rog, Sherab Ö.]

'dir rog gis de rnams thams cad kyi dgongs pa cig tu gril ba yin ste / rma'i lugs mthar thug pa yin no // • //

[It was Rog who rolled up all of these transmissions into a single intention, bringing the Rma School to its full expression.]

[The precepts that emerged from them: the Meaning Transmission of direct recognition, and the Word Transmission that resolves doubts]

gnyis pa de las byung pa'i gdams pa la gnyis ste / don gyi rgyud pa la ngo sprad pa dang / tshig gi rgyud pas sgros 'dogs bcad pa'o //

dang po la lnga ste / bcud kyis rang rig pa'i ye shes ngos bzung pa dang / thun gyis ting nge 'dzin srangs su gzhug pa dang / rtsal sbyong gis bogs gdon pa dang / sor bzhag gis phyag rgya chen po ngos bzung pa [4v] dang / la bzlas bsgom du med par bstan la dbab pa'o // • //

tshig gi rgyud pas sgros 'dogs bcad pa la lnga ste / sems bskyed lam khyer gyis byang chub kyi sems khyer ba dang / stong thun gyis shes bya bstan la dbab pa dang / kha thor gyis don gyi mdo' gzung pa dang / kha phog snar phog gis stan la dbab pa dang / tha ma mthar rgyas gnyis su la bzla ba'o //

[Written documentation]

de la yi ge de rnams la che chung 'ong pa ni / phal cher rgyas bsdus kyi khyad par yin pas / chen mo rnams chung par 'dus pas / logs su mi dgos so //

stong thun chu rgyun dang / 'bring po dang / sems bskyed chu rgyun ni / logs pa yin pas chen mor ma 'dus pa yin no //

gzhan khar phog brgyad pa dang / bcu' gnyis ma gnyis ka / stong thun 'bring po yang chen mo dang 'dra / rgyas bsdus yin / sems bskyed 'bring po yang chen mo 'dus / dpe dang phan yon gnyis kyi khyad las med / kha phog la che chu [~chung] med / khu bsgom gyis lhug par bkod pa la rten nas / chus pas tshig bshad du byas yin no // //

[These just-listed written texts were made by Chüpa (Chus-pa) in reliance on the loose arrangement by Khugom.]

rma lugs kyi lo rgyus rdzogs s.ho // // // // //

[The History of the School of Rma is hereby completed.]

•

Appendix B: Notes on the Four Rma Lineage Manuscript Fragments from Matho, Ladakh

v123

Fols. 1-2, 6-7, 10 (on verso is a kind of ending), 62 etc. The final scan p. 22 contains a colophon that identifies it as written notes of “Khutön myself” with Khutön being none other than Khugom: rje btsun rgya gar gi bdam ngag xxx rje btsun rma'i snyan rgyud la / rje btsun dga' ldan pa'i (?) stong thun // baxx bxx khu ston bdag gi zin bris so // rdzogs s.ho. This surely pertains to a Mahāmudrā lineage of Padampa’s precepts in the transmission from Rma, and is in the very same lineage as the Khugom texts found elsewhere among these fragments. Rma (b. 1054) taught Ganden, who in turn taught Khugom. Since Khutön (Khugom) refers to himself as the one who took down the notes, this text’s composition ought to date to his time, in the middle decades of the 12th century.

v249

[1] First folio labelled “3 dug 'go ma. I’m inclined to think this first fol. is a Padampa text, even if it makes use of a term uncharacteristic of him, “la-zla-ba” (passing over the pass). Scan no. 2, in its last lines, says “Do not teach this to all, keep it in a one-to-one transmission.” I notice use of the unusual word sna-ga (=sna-ka), meaning 'all [the] sorts of.' [2] The following fols. are marked as nos. 47, 57, 62, 92. Fol. 47 is definitely a Padampa text (the others require closer study), containing his direct teachings to women disciples (it has been utilized somewhat in this earlier blog). Fol. 62v has a colophon: dam pa rma (?) / zhang gsum gyi gsung ngag / bla ma khu'i gsungs 'gros / myi 'gyur [mi 'gyur] bdag gis yi ger bkod pa / lta ba 'i bste sgor lnga ba (?) // rdzogs s.ho / si ta sang ge ho. This is explicit about Mingyur setting down in writing the teachings of his Lama Khugöm that contain the oral precepts of Padampa, Rma and Zhang [Gandenpa].

v263

Two fols. only, no fol. nos. Both individually appear to be beginnings of texts, and both are surely Zhijé. 1st fol.: Mention of “Dam pa Sangs rgyas” at end of line 2 of scan p. no. 1, so quite evidently a Zhijé text. But note on line 6 mention of “rang byung ye shes” (intrinsic Full Knowledge), not a characteristic phrase of Padampa, and so likely indicating Nyingma influences that entered in after Padampa’s death in 1105. It quotes from the Guhyasamāja Tantra and from Dohā songs. At the end of 1st fol. is a colophon we’ve seen before: bla ma khu sgom gis / myi 'gyur bdag la phyis gnang ba'o / dam pa'i gdams pa... I see here, too, that this text is to be regarded as belonging to the Meaning Transmission (don-gyi rgyud-pa). 2nd fol.: The beginning of the 2nd fol. (scan p. no. 3) states that it is the Intermediate among the three Word Descents (Bka’-babs ?) from Dampa, and among the three intermediate lineages, it is that of the Rma. This number as a whole ought to cover both bodily and mental preparations for meditation practice, although what we have here scarcely covers the bodily preparations, much resembling the well-known Dharmas of Vairocana. The full text would have covered much more.

v285

I believe the text begins on the scan p. no. 2, and continues on scan p. 1. It explicitly states it contains precepts of Rma among the three [Middle Transmissions] Rma, So, and Skam (a statement quite similar to v263, listed above). The 2nd fol. (scan p. 4, line 4), has a colophon like we’ve seen before: don kyi rgyud pa rje btsun khus myi 'gyur bdag klu'i nang du gnang ba'o / chos kyi dbyings la ngo sprad pa / shin tu mtshan ma myed pa'i gcud // // rdzogs so. So definitely, the two folios together are [one?] Zhijé text. The Khu mentioned in the colophon is certain to be Khugom Joga, spiritual grandson of Rma. This is explicitly included within the Meaning Transmission.

•

Appendix C: Drametsé Thorbu 041, title list with a few notes

Title 1. [1r] Brgyud pa bar pa'i lo rgyus kyi rim pa. 5 fols. [ends p. 5v]. This is a history of the So lineage of Zhijé by Rog Sherab Ö.

1v.6 Birth of Padampa.

2v.1 The Schools that formed after him: Early, Middle, Late.

2v.6 How he met So.

3r.4 Lama So requests teachings. More names of teachers.

5r.5 Rong Ban dhe Shes rab 'od.

Title 2. [1r] Another Zhijé history, with biography of Padampa etc. and an account of the Middle Transmission Skam lineage. 6 fols [ends p. 8b].

3r.1 Padampa goes to O rgyan.

4v.5 Goes to Chu mig ring mo. 4.6 Goes to G.yu ru Gra thang, meets Dge bshes Gra pa.

5r From here on, it is about the transmission to Skam (i.e., a Skam lineage account).

6a.6 A passage explaining how there was a split in the transmission, that there are upper and lower traditions, and that this is the upper one. There are lineages given, all ending in Rog Sherab Ö, and in fact the colophon is unambiguous that he was the author of this text.

[no title]

Incipit [1r]: bla ma dam pa rnams la phyag 'tshal lo //

dam pa rnams kyi zhal nas gsungs shing snyan nas snyan du rgyud pa'i gdams pa la / sngags dang pha rol tu phyin pa gnyis su gnas / de la pha rol tu phyin pa'i gdams pa la / gang zag yid ches par bya ba'i phyir / bla ma rgyud pa'i rim pa gtam rgyud yi ger bkod par bya'o // //

Title 3. [1r] Kar sna ka ri thugs kyi sras / gnyis myed bla ma rma'i brgyud. 9 fols. [ends p. 15a]. A historical account of the Rma lineage.

Note: I think the kar-sha-ka-ri must intend "Krishnakari," or the like, as an epithet of Padampa with reference to his blackness. This work is an interesting combination of lam-rim, meditation manual, philosophy text, with strong hint of medicine (and bcud, nutrition), Mahâmudrâ.

[1r] kar sna ka ri thugs kyi sras //

gnyis myed bla ma rma'i brgyud //

'gro ba'i log rtog sel mdzad pa //

brgyud pa rnams kyi zhabs la 'dud //

rje'i zhal gyi bdud rtsi' chus //

blo rman 'tshal bar 'dod pa yis //

rje btsun dam pa'i gsung sgros 'di //

cung zhig bdag gis bri bar bya //

Title 4. No title. 5 fols. [ends p. 18c], a text of the Rma lineage written down by Rog.

No title (but it calls itself Rma'i gdams phra gcod 'di...).

Incipit [1r.1]: Om swa sti // spros dang spros med las grol zhing // dmigs dang dmigs med rnam par spangs // brjod med brjod pa kun gyi mchog // lhan cig skyes la 'dud phyag 'tshal //

Colophon [5v.4]: de ltar gdams pa thor bu ba ma lus pa // mthor kyis dogs nas cig tu gril ba 'di // rog gi ban dhe bdag gis yi ge bkod // nongs par gyur na bla mas bzod par gsol / 'bum si lu* zhes bya ma // bla ma rin po che rog gis bkod pa // rdzogs s.ho // dge'o // [*I notice there is a text with sil-lu in its title in the Zhijé Collection.]

Title 5. Untitled text of Rma lineage in 5 fols. set down by a disciple of Rog Sherab Ö. It says it belongs to the Rog school.

Colophon [5v.8]: mthar rgyas gnyis kyi gdam ngag / 'jam dpal smra ba'i seng ge la / dpal bhir rgya ba la / des a rya de ba la / des ka ma la shi la / des rma bsgom / des zhang dga' ldan pa / des khu bsgom / des rog shes rab 'od la / des bdag la gnang pa lagso // mthar rgyas kyis la zla ba // rdzogshyo // rin po che rog gi lugs so // ithî // //

Text 6. No title. Rma lineage text. 4 fols. [ends p. 24c].

1r.2 This is the School of Rma. 1r.3 lineage given. Incipit [1r.1]: bla ma dam pa rnams la phyag 'tshal lo // rje dam pa rgya gar ba chen po sprul pa'i sku / nyi ma dang zla ba ltar du grags pa / 'dzam bu gling gi rgyan chen po des gsungs pa'i chos lags / bla ma chen po des gsungs pa'i chos la / spyir rgyud pa'i bka' srol mang kyang / 'dir bla ma rma'i lugs lags //

'di yi gdams pa la spyi don gsum / bsgrub byed kyi brkyen bstan pa dang / de'i rten bstan pa dang / gdams pa dngos bstan pa'o //

de la rkyen bla ma ste / rgyu sems can gyi sems nyid lhan du skyes pa rang la gnas kyang / rkyen bla mas ngo sprad na mi rtogs pas / de'i phyir bla ma ni / rje dam pa rgya gar ba / rma chos kyi shes rab / zhang dga' ldan pa / khu bsgom jo dga' / rgyal pa [rgyam pa?] dang chus pa / bla ma rin po che la sogs pa'o.

Colophon [4v.6]: de rnams ni rma'i chos sde sum bcu rtsa gnyis so // iti // //

Text 7. No title, but after the homage, a kind of title reads [1r.1]: Khro bo rigs pa'i rgyud pa zhes bya ba. I noticed nothing indicating this would be a specifically Zhijé text. 14 fols. [ends p. 32c].

Followed by an outline: 'di'i spyi don drug gis stan ste / bde bar gshegs pa bzhi / des gsungs pa'i gdams pa bzhi / khro bo bzhi / de'i lta stangs bzhi / de'i ngo sprod bzhi.

3v.2 Lists some other esoteric traditions including Spyal gyi slab tshig ring mo (I believe the Bslab tshigs ring mo was a teaching of Dpyal, in fact).

Colophon [12v.6]: kha 'thor chen mo bcud phur bcu brgyad gyi gdams pa 'di // bla ma'i gsung la nan tan byas nas yi ger bris // 'di bris dge ba phyag rgya chen po'i don rtogs nas // 'gro kun thar pa'i lam du 'dren pa'i bdag por shog // kha 'thor bcu brgyad ma / bcud phur gyi gdams pa'o // rdzogsho // // [2 tiny letters follow]

Text 8. Untitled precepts of the Rma (or possibly Skam?) lineage. 16 fols. [ends p. 43a]. This must be a work of Rog Sherab Ö that reached Chüpa.

Small letters above line 1: khu bsgom gyis ltug pa la / chus pas tshig bshad du bsdebso [compare colophon of no. 11 below]. Lineage at 1r.2: rkyen sprul sku ma rgya gar des // las dang ldan bar ldan pa'i rma la gdams // rma'i brgyud pa rje btsun dga' ldan pas // thugs kyis bzung nas sras mchog khu ['khun dbang phyug rdo rje of other sources] la gdams // de yis rjes bzung rje btsun rgyal pa yis [rgyam pa? rgyams shes rab bla ma of other sources] // thugs rjes bzung nas bdag la rjes su gnang // zhal snyan brgyud pa'i bka' babs de ltar ste / las 'phro mtshams sbyar brgyud pa'i khar phag go // [small letters: chus pa rag {~bdag?} la thug go. Note: This must mean 'Chus-pa Dar-brtson of other sources].

Text 9. Skabs dang po'i gdams pa. 6 fols. [ends p. 47a].

Colophon [6r.6]: shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa snyan rgyud kyi gdam ngag ces bya ste / rje rgya gar rin po che'i zhal snga nas legs par gsungs pa'i don // ma lus par rdzogs s.ho // [added in a different hand in dbu-can script: rdzogs pa'i sangs rgyas thob par shog].

Text 10. Yul bden pa bzhi'i gdams ngag. 23 fols. [ends p. 61c]. A work of Rog Sherab Ö.

17r.2: [Skt. title] Ting nge 'dzin gyi las brgyad zhes bya ba.

Colophon [23r.5]: bka' bden pa bzhi'i chos kyi 'khor lo zhes bya ba / rog gi ban dhe shes rab 'od kyis // bla ma'i gsung sgros yi ger bkod pa'o // // rdzogs s.ho // legs so // dag go.

17v An uncompleted prayer, with erasures at the end, in a different cursive hand.

Text 11. No front title. Rma lugs kyi lo rgyus [title from colophon]. 4 fols. [ends p. 66a]. A history of the Rma school, surely authored by Rog Sherab Ö. This was transcribed in Appendix A.

Starts with a Pha dam pa biography, then a biography of Rma.

2r.5 zhang dga' ldan pa'i lo rgyus.

3r.8 de la khu bsgom dang 'byal ba'i lo rgyus ni [the story of his encounter with Khu sgom].

4v.5 khu bsgom gyis lhug par bkod pa la rten nas / chus pas tshig bshad du byas yin no.

Colophon: rma lugs kyi lo rgyus rdzogs s.ho // // // // //

Text 12. No front title. On subject of lus gnad & sems gnad. 3 fols. [ends p. 68a]. In content this closely resembles Matho fragment v263.

[1r] rje btsun dam pa dri myed zhal //

'gro ba'i log rtog sel mdzad pa //

brgyud pa rnams kyi zhabs la 'dud // //

bla ma rje dam pa rgya gar gyi bzhed pas //

gang zag cig bla na myed pa'i byang chub bsgrub par 'dod pa la / chos rnam pa gnyis dang ldan dgos ste / lus gnad la dbab pa dang / sems gnad la dbab pa'o //

Colophon [3v.5]: de ltar ngos sprod brgyad kyi lam khyer ro // rma'i ngos sprad brgyad pa // sems bskyed lam khyer chung kuno // rdzogs s.ho.

Text 13. Evidently title page is missing. fols. 2-32 [ends on p. 88b]. I doubt there is a Rma or Zhijé lineage text hiding here. There are a number of subtitles hiding here.

A typology of illnesses [7v.7]: lus kyi na tsha la gsum ste / 'byung pa' na ba dang / dgegs kyis na ba dang / sngon gyi las kyi rnam par smin pas na ba'o //

[17r.1] rgya gar skad du / sa man ti kar ma ba si na ma // bod skad du / ting nge 'dzin gyi las brgyad zhes bya ba // shag kya thub pa la phyag 'tshal lo //

Colophon [27v.4]: phyag rdor bha ma ma'i dbang khrigs [~khrid] gzhung dang phyag bzhes 'du btsun pa / rin chen phreng ba zhes bya ba / 'go ban nor bu la / snod ldan bus yis bskul nas bkod pa // rdzogs s.hyô // dge bar gyur cig // 'go mu ne ke du'i thugs dam ['go nor bu is found just below] / ban chung 'gar gyis bris pa'o [small letters not transcribed here].

Colophon [31v.8]: Illeg. red letters. skal ldan bu yis gsol ba gtab don du // snga ma'i [32r] cho ga cung zad mi gsal ba // legs par gung sgrigs phyag bzhes rtsor byas nas // 'go'i ban dhe nor bus gsal bar bkod // dgon gnas [?] 'gro don rgyas par 'phel ba dang / phyag na rdo rje'i go 'phangs thob par shog // dbang chog rin chen 'phreng pa zhes bya ba / spre lo dbyar zla ra ba sbrul zla'i zla stod dkar po'i phyogs la rtsi lung dpal gyi dgon pa'i gzims khang lho phyogs su tshes gsum nas bcu drug gi bar du tshar bar bkod pa / thugs sras rnams dang snod ldan gyi bu slob rnams kyi don du gyur cig // // bkra shis shing zhal dro ba dang smon lam bka' rtsan zhing byin che bar gyur cig // legs so / dge'o // // rdzogs so.

Volume colophon (?) [32v.5]: thugs sras rnams dang bu slob rnams zhes pa'i don ni / bstan pa'i bdag po shag kya'i mtshan / dgos 'dod 'byung ba'i rin chen dang / sra zhing brtan pa rdo rjer grags // tshogs chen gnyis logs bsod nams rnams // phyogs bzhi mtshams bzhi slob bu kun // don byed phyag rdor dbang khrigs bkod // ces pa lags so // 'di bris dge bas 'gro bzhi kun gyis phyag rdor gyi go 'phang thob par shog / ban chung 'gar* gyis bris so // [Note: All the smaller letters in this section I believe belong together, and were probably added later on, filling in spaces left by the original scribe, so here they are, starting near the end of line 6:] dpe 'di dka' srung rdo rje bdud 'dul** rtso 'khor lnga la stod [~gtod?] / [.7] zhu dag dgyis te dag dper bzhugs.ho / [There is another line, hard to read, and perhaps with no substantial information.]

Note: The remaining pages of photos after no. 88 were not printed as they are not Zhijé texts, although the last one is particularly interesting; a work of Götsangpa (1189-1258) with the title: Cha snyoms [~ro snyoms] kyi zhal gdams gsal ba'i me long... don 'grel Rgod tshang pas.