|

| Matho manuscript fragment W1BL9 v314 |

It’s been two decades since that essay about early Tibetan women religious leaders entitled “The Woman Illusion?” The book is nowhere near being closed on this subject. But we can confidently start off where that essay concludes: Nowhere are more 12th-century women’s life stories told than in the immediate circle of Padampa and the early Zhijé school. This wasn’t only due to Padampa’s open attitude,* but perhaps even more to his Tibetan disciple Kunga, the one responsible for all or at least most of the relevant literary collections. Kunga was the one who, quite literally, took note and, well, took notes.**

(*I suppose this may have something to do with the fact that a lot of Padampa’s mentors while he was in India were women, and those same Indian women’s teachings feature prominently in the collections. Another factor to consider, since hardly any women in Tibetan history received full Bhikṣuṇī ordination as nuns, and since most streams of the established schools had little or nothing in the way of lay leadership, laywomen were in a similar, if somewhat worse situation as laymen. Padampa and his early Zhijé followers as well as the early Kagyü openly encouraged serious lay participation at every level of Buddhist endeavor. **Kunga took notes on bits and pieces of paper that he tied up in bags and hung from the ceiling, much as bags of salt might be hung to avoid damaging moisture. But more explorations into the process that led up to the Zhijé Collection as we know it another time. I find it fascinating, frankly.)

To introduce a few more threads before attempting to spin them together: In an earlier blog called “Alchi Padampa’s Meaning,” we considered in what ways Ladakh might be connected with Padampa and the early Zhijé tradition. Apart from artistic depictions that suggest Padampa’s special importance to Kagyu Ladakhis in the past, I admit I’ve hardly noticed anything. Even in the Alchi depiction, just to point out my best example, it seems (or rather seemed at the time) best explained as an esoteric Shangpa Kagyu visualization practice, and not anything pertaining to Zhijé traditions directly.

But all that has changed, and with unexpected speed. We now have evidence to show that Zhijé was much more important in Ladakh than has been thought, at least back in the 12th century. We can even state with confidence that local Ladakhi Zhijé practice is by itself sufficient to explain those uniquely Ladakhi depictions of Padampa holding a cane flute (see this recent blog for more).

Thanks to the Matho fragments, we have pre-1200 CE textual fragments taken from chortens that had been disassembled, their content now preserved for us in a monastic museum. You may be thinking I’ve recently traveled to Ladakh, otherwise how could I know this? Well, it can’t possibly be true, but still I sometimes imagine I am the only one who checks the weekly “recent acquisitions” list in BUDA website of new scans posted there.

The website and Tauscher’s essay agree that those no-longer-to-be-seen chortens in the vicinity of Matho were closed at the end of the 12th century (or possibly as late as two decades into the 13th, but really, no later than that), and in my judgement the couple of fragments that hold our attention today are no exception. More fragments with other revelations will figure in future blogs, but today we’ll focus on a few in particular.

The first you can see floating in the sky above the mountains in our frontispiece. If you are like me, you will notice the proper names, and your first idea might be that this is the relatively well-known set of Padampa’s women disciples’ life stories (in English in the Blue Annals, and in Italian in Gianotti’s book). This is not entirely wrong. But on closer inspection there is at least one thing very distinctive about it. It has not only brief sets of facts about their lives, usually limited to a line or two in the text, but many more lines record a master-disciple interview in which the disciple states a problem or asks a question, and Padampa in his inimitably elliptic and even cryptic way, answers her with answers that raise all kinds of robust and healthy questions for us 21st-century interpreters. These aren’t exactly the same as the encounter dialogues of early Chan/Zen. On the other hand, they aren’t entirely different. We should at least be prepared to reflect on them with an open mind.

I see no sign that these interviews were in any way public, although I suspect Kunga was present as a third participant. I think this is suggested by his words in the colophon. In any case his presence was often required because even if Padampa said what he said laconically and in Tibetan language, his poetically metaphoric/parabolic and spiritually symbolic expressions always required some unpacking. Although overstated, it could in some degree be true what is sometimes said, that Kunga was the only one who understood those symbolic expressions. And just because his presence as an interpreter was needed, it put him in a perfect position to record his sayings for posterity, and that is why we have the good fortune to be able to ponder them today.

Last year, when I first saw these Matho fragments of the teachings for women, I was troubled that they seemed to be unique in combining the precepts with the life stories. The Zhijé Collection has two titles involving three separate texts entirely devoted to women, two of them collections of precepts, the third a collection of life stories.* It is only this last mentioned text, the one with the life stories, that has been published about.

(*The first might be given the title Thun-tshags-kyi Dum-bu, or Interspersed Bits and Pieces, based on words found in the colophon, even though the real title would be the one that is entirely invisible in the published version: Dmug-po Mchong-gi Skor, or Maroon Carnelian Cycle. This is found in ZC, vol. 2, pp. 440-460. The other set of precepts is found under the title Jo-mo Nyi-shu-rtsa-bzhi’i Zhu-lan Lo-rgyus dang bcas-pa in at ZC, vol. 4, pp. 302-313. The collected biography follows at ZC, vol. 4, pp. 314-323. This last served as the basis for the passage in Blue Annals, pp. 915-920, although as we’ll see the Blue Annals is often severely abridged. See the example of Jomo Penmo, below, for further clarification. I’ve neglected the Maroon Carnelian for now, and may return to it another time.)

It seems like only yesterday that I first knew of any text, whether fragmentary or whole, that agreed with the Matho fragments in combining precepts with life stories. I located this largely parallel text in ZCK (see below for details). In my excitement which I can only hope some other people will share, I made a comparison of the two texts to try to understand better how things stand. This non-fragmented text was put up on the internet just a few years ago. In the appendix (see below) the Matho fragment is given primacy in large Tibetan letters, while the text found in ZCK is in smaller-sized Romanization.

* * *

Written resonance

For an introductory account of the Matho fragments see a recent Tibeto-logic blog: The Only Terma among the Matho Termas.

For the hurried handlist, look here.

Carla Gianotti, “Female Buddhist Adepts in the Tibetan Tradition: The Twenty-four Jo Mo, Disciples of Pha Dam Pa Sangs Rgyas,” Journal of Dharma Studies, vol. 2 (2019), pp. 15-29. Look here.

_____, Jo mo. Donne e realizzazione spirituale in Tibet, Ubaldini Editore (Rome 2020).

This contains an Italian-language translation of Kunga's collective biography of twenty-four women disciples of Padampa. The title that appears in the Zhijé Collection version reads: Jo-mo Nyi-shu-rtsa-bzhi’i Zhu-lan Lo-rgyus dang bcas-pa.

_____, “The Lives of the Twenty-Four Jo-mos of the Buddhist Tradition: Identity and Religious Status,” contained in: Karma Lekshe Tsomo, ed., Contemporary Buddhist Women: Contemplation, Cultural Exchange, and Social Action, University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong 2017), pp. 238-244.

Dan Martin, “The Woman Illusion? Research into the Lives of Spiritually Accomplished Women Leaders of the 11th and 12th Centuries,” contained in: Janet Gyatso and Hanna Havnevik, eds., Women in Tibet, Hurst & Co. (London 2005), pp. 49-82. A pre-published version is posted here.

Helmut Tauscher, “Manuscript Fragments from Matho: A Preliminary Report and Random Reflections,” Revue d'Etudes Tibetaines, vol. 51 (July 2019), pp. 337-378. Freely available online.

ZC — The Tradition of Pha Dampa Sangyas: A Treasured Collection of His Teachings Transmitted by Thugs-sras Kun-dga’, “reproduced from a unique collection of mss. preserved with ’Khrul-zhig Rinpoche of Tsa-rong Monastery in Ding-ri, edited with an English introduction to the tradition by B. Nimri Aziz,” Kunsang Tobgey (Thimphu 1979), in 5 volumes. It would be best to use the NGMPP photographed microfilm, and for details on it, you may look at this BUDA page about L/296/4.* Look at the illustration just below, the topmost text on the page, but also try seeing it in the 1979 "reprint" publication of the very same manuscript where it is entirely absent.

(*Or, to give the URL: http://purl.bdrc.io/resource/WA0NGMCP48027.)

|

| ZC (film version) keyletter KHA, fol. 152 verso (click to expand) |

Several works of particular relevance to Padampa’s women disciples are contained in ZC, but the main one for present is the one at vol. 2, pp. 440-460. As we mentioned before, in the published volumes its title is not visible and must be restored from the NGMPP film version: Dmug-po Mchong-gi Skor. Although complete and detailed comparison remains to be done on how this Cycle of Maroon Carnelian differs from the Matho fragment and the work in ZCK.

The other most important text devoted to Padampa’s women disciples is located in ZC, vol. 4, pp. 302-323, with the title Jo-mo Nyi-shu-rtsa-bzhi'i Zhu-lan Lor-rgyus dang bcas-pa.* It differs from the Matho fragment and the work in ZCK primarily in its different arrangement of the same or similar content. It supplies one set of precepts for women followed by a set of biographical sketches of the same women. The Matho and ZCK texts seem to be the only ones to combine the two into a single set.

(*Although this is not the place to list them all, there have by now been a number of republished versions of this. For instance: Jo-mo Nyi-shu-rtsa-bzhi'i Zhu-lan Lo-rgyus dang bcas-pa, contained in: Shug-gseb Rje-btsun-ma'i Gsung Rnam sogs, Gangs-can Skyes-ma'i Dpe-tshogs series no. 7, Si-khron Bod-yig Dpe-rnying Bsdu-sgrig-khang (Chengdu 2015), pp. 280-294. It is copyrighted and not made available, I have no print copy, and no straightforward way of ordering one.)

ZCK — This is my invented abbreviation for a one-volume manuscript set entitled Zhi-byed-kyi Chos-skor. It is unpublished, although posted by BDRC as a downloadable PDF (just place “W3CN25705” in the search box at the BDRC site). In today’s blog we only make use of its section with keyletter TSHA, a 7-folio collection of precepts for women with the title Gzhan-rkyen Jo-mo Nyi-shu-rtsa-lnga’i Zhus-lan, Answers to Questions of the Twenty-Five Jomo (for a discussion on the meaning of gzhan-rkyen, see below).

+++ +++ +++ +++ +++

Appendices

Here and now two of the Matho fragments will be compared to the only known closely corresponding text. That means the one found in ZCK, a one-volume handwritten Zhijé set made available in scanned format by BDRC only in the year 2021 (it can be located using BDRC's call number W3CN25705).

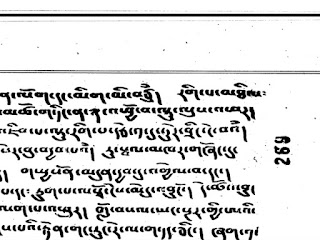

The Content of Matho no. v314:

The first 4 fols. actually have within them (at the end of the folio marked “48”) the colophon of the text of Padampa’s teachings to his women disciples, supplying the title Jo mo nyi shu rtsa bzhi la bsdams pa / Kun dgas yi ger bkod pa (“Precepts for the Twenty-Four Jomo, Set in Writing by Kunga”). Now I believe this *is* the same as the biographies of the 24 Jomo, however the version represented in Matho fragments is different from those previously available (as found in ZC, in Blue Annals for examples), as each biography is preceded by a specific teaching Padampa gave to that woman disciple. As the 2nd folio isn't presently relevant we will neglect it. The 3rd folio marked fol. 42, is another folio from the same collection of teachings to Padampa's 24 women disciples. (The 4th folio is just a repeat scan of fol. 48, as found in the 1st folio, just it is a little clearer to read.)

The Two Textual Witnesses for Comparison:

I’ve taken the two folios marked as “47” (from v249, where it also appears in a black-and-white and enlarged scan) and “48” (from v314) and transcribed their cursive into Tibetan block letters. I’ve extracted the corresponding passages from ZCK and transcribed them into Wylie transliterations, indented. I have for the time being neglected two other pages I’ve identified as belonging to the same text, folios 20 (from v324) and 42 (in both v246 and v314). For present purposes I have used the longest continuous piece of the text, and the one that includes its conclusion. Added notes (by the original author or by a later follower of the tradition, in either case dating no later than 1200 CE) are inserted in what I regard as an appropriate enough place using dark blue font color, while dark red font color is used for designations for the women (most are true proper names, but at least one is only descriptive).

Nota bene! I’ve made a beginning for a very tentative translation in green font color, and may revise it and add the other two folios as time goes by.*

(*This translation is based on whichever of the two versions makes better sense to me right now. I’m prepared to admit this is a problem, although I try, not always with success, to adhere to the Matho text.)

Acknowledgement! At one point I stopped and was unable to go further. I failed to make any sense at all of no. 19. It is only thanks to the help of Naljor Tsering that I could continue. It could not have been done without him.

Apology! I only supply this roughed out translation as a reference point for those who cannot despite their best efforts read Tibetan. Those who do read Tibetan with considerable ease are requested to ignore the English and limit themselves to enjoying, or struggling with, or enjoying the struggle with, the Tibetan. If I had started making philological discussions justifying each of my translation choices, there would be no end of it.

[47r from duplicated scan in Matho v249]

ཇོ་མོ་ཅན་མོ་ལ། དམ་པའི་ཞལ་ནས་། སྟོག་པ་མྱེད་པ་ལ་ནད་འདྲེ་ལ་ཉམ་ང་བྲག་ཚ་ཡོད་དེ་། སྟེ་། ཚོགས་སོག་པ་ལ་དགའ་བྲོད་བྱེད་ཀྱིན་མཐའ་རུ་མྱི་འབོར་གྱིས་།

[ZCK, fol. 6r.7] jo mo phan mos dam pa la zhus pas / rtog pa med pa la nyams nga ba [7r] bag tsha ba yod de / tshogs bsags pa la dka' na / longs spyod kyi mi 'bor gyis

When Jomo Penmo asked a question of Dampa, he said, “Those devoid of realization are possessed of weariness and shame [sickness and spirits]. If it is difficult to lay up stores of merit, don’t squander wealth and leisure.

སྨད་མ་ཁྱོད་ཚོ་། སྨད་ཀྱིས་ཅང་མ་ཉོ་བར་ཚེ་ཕྱི་མ་འི་ཆོས་དགོས་སམ་མྱི་དགོས སྣང་བ་ལྟོས་། རང་ལ་མ་སྟོད་། གཞན་ལ་མ་སྨོད་། ཏིང་ངེ་འཛིན་ལ་ཁའི་བྱ་སྐད་ངག་སྐུག་པར་སྡོད་ཅིག་མ་སྨ་བར་ཞོག་། བླ་མ་དཀོན་མཆོག་ལ་གསོལ་བ་སིངས་སིངས་ཐོབ་། ཕྱི་མའི་དོན་དེས་གྲུབ་ན་ཡོང་གསུང་ངོ་།

smad ma 'tshong chang ma nyo / kha snang phyir phyir ma lta / rang la ma bstod / gzhan ma smad / ting nge 'dzin la ka'i bya sgro bzhag / gsol ba thobs / phyi ma'i don 'grub ste 'ong gsungs /

Don’t sell your loins, don’t buy beer. Have no regard for the superficial [for the sake of appearance]. Don’t praise yourself, and don’t put others down. Remain in meditative concentration, make birdcalls in space, don’t speak (live in silence). Make resounding prayers to the precious Lama. That will secure a better rebirth.”

ཇོ་མོས་དམ་པ་ལ་ཞུས་པ་། སྤྱད་རྒྱུ་ཚོགས་ལ་མྱེད་། དབུས་སུ་ཕྱིན་ན་ཡིད་དམ་དང་བྲལ་། དམ་པ་བདག་གིས་ཅི་ལྟར་བརྒྱི་ཞུས་པས་།

phan mos zhus pa / spyod rgyu'i tshogs sogs nga la med / dbus na phyin / dam pa dang mjal / dam pa bdag gis ci ltar bgyis zhus pas /

Penmo addressed Padampa, “In the assembly I have nothing to do. If I go [back] to Central [Tibet] I will have no spiritual focus. Dampa, tell me what am I to do?”

དམ དམ་པའི་ཞལ་ནས་བསླངས་ནས་ཟ་བ་རྒྱལ་པོ་ཡིན་། མྱི་ཟས་ཟ་བ་འཁོལ་པོ་ཡིན་། འཚོའ་བ་ནམ་ཀ་འི་དཀྱིལ་ནས་སྦྱོར་། དིང་རིའི་སྟོང་ན་མཛོད་ཡོད་། ཕྱག་འཚང་ཟུ་[?]མོ་ལ་འཁས་འགྲོ་སྡེ་བཞི་བྱེད་། གཟའ་དཔོན་དམ་པ་ཨ་ཙ་ར་ནག་པོ་བྱེད་།

dam pa'i zhal nas / bslangs nas za ba rgyal po yin // mi zas za ba khol po yin // 'tsho ba namkha'i dkyil nas sbyor // mdzod ding ri gdong na yod // phyag tshang mkha' 'gro sde bzhi yod // gza' dpon nag po a tsa ra //

Dampa said, “If you eat from a tureen, you're a king, but if you eat human fare you’re a slave. Prepare your meals from the center of space. In the empty place of Tingri is a storehouse. We have the four classes of skygoers as kitchen help. Our master chef is the black acharya Dampa.”

དེར་ཕན་མོས་འདུགས་པས་། ཟས་གོས་ཕྱིད་ཅིང་འདུགས་པས། ཡོན་ཏན་མང་པོ་ཤར་ནས་གྲོལ་ལོ་། ཇོ་མོ་ཕན་མོ་། ཡུལ་ཕན་ཡུལ་མ་། བླང་ཁོར་དུ་ལོ་བཅའ་བརྒྱད་བཞུགས། བླང་ཁོར་དུ་གྲོངས་སོ་།། ༑ །།

der phan mos 'dug pas zas gos phyid cing / yon tan du ma shar ro //

There Penmo remained, lived to her old age with sufficient food and clothing until she was finally liberated displaying various good qualities. Jomo Penmo was a native of Penyul, lived 18 years in Langkhor, and died in Langkhor.

•19•

ཇོ་མོ་རྗེ་འུ་ལ་། དམ་པའི་ཞལ་ནས་། ཁྱོད་རྒྱ་ཟོར་ཅིག་བསུངས་[~བརྡུངས་?]ལ་། རྩ་སྔ་རུ་བཏང་ངོ་། རྩ་གཤིན་མྱི་གཤིན་མྱེད་ཀྱིས་། གང་འདུག་ [47v] ཏུག་ཕྲད་དུ་སྦྲེག་ལ་ཤོག་ཅིག་།

jo mo rje 'u la dam pa'i zhal nas / khyod rgya zer gcig brdung la rtsa rngar btang gsung / rtsa gshin mi gshin med kyis / thug gnyis snang gcod pa phrad breg la shog cig /

Jomo Jeyu, Dampa said, “You are to forge a scythe and cut the grass. No matter if it is thick or thin, whatever grass you encounter, mow it down!”

ཉོན་༷༷༷ [?] པ་ཐུག་སྤྲད་དུ་ཆོད སྟ་ཁྲ་བོ་སྣང་བ་ཁྲོ་བོ་གང་ལ་ཡང་ཤེས་རབ་ཟས་སུ་ཟ་འོ་། ཁུ་རུ་དེ་སྙིང་གར་སེམས་ལ་ཁུར་ལ་ཤོག་ཅིག་གསུང་པ་། མོས་རྩ་མ་སྔས་པར་། བཅད་སྦྱོར་གྱི་སྣང་བ་ཐུག་ཕྲད་དུ་ཆོད་། སྣང་བ་ཆོས་ཉིད་དུ་སྦྱོར སྨན་ཅིག་བླ་མ་ལ་ཕུལ་བས་། བླ་མ་མོ་ལ་མཉེས་སྟེ་།

rta khra bo shes rab za'o gang yang za'o // khur po snying khar khur la shog cig byas pas mos rtsa ma rngas bar / bcad sbyor gyi chos nyid rang la sbyor ba sman cig bla ma phul bas/ bla ma mnyes te

The piebald horse (variegated phenomenon), regardless of what it is, eats it (insight has it for food). For its heavy load bear the burden in the heart (in the mind).” The woman didn’t go out to mow grass, but instead offered the Lama a prepared (the true nature of Dharmas compounded with itself) medicine. This pleased the Lama.

མོ་བརྡའ་དེས་གྲོལ་ནས་ སྣང་བ་ཏུག་ཕད་ལ་གཅོད་ཤེས་པ་ཅིག་བྱུང་ངོ་། ཇོ་མོ་རྗེ་འུ་མ་། ཡུལ་མྱེད་། བླ་འཁོར་དུ་ལོ་མང་དུ་བསྡད་། དམ་པས་གུང་ཐང་དུ་སྡོད་ཅིག་ལུང་བསྟན་། གུང་ཐང་རང་དུ་གྲོངས་སོ་།

mos brda de khrol bas thug phrad gcod shes pa gcig byung ngo /

She disentangled the meaning of the symbolic language, so she knew it meant to cut phenomenal appearances directly as they are encountered. Jomo Jeyuma had no home region, but she stayed many years in Langkhor. Once Dampa predicted, “You will stay in Gungtang,” so it was in Gungthang that she died.

•20•

ཇོ་མོ་འབར་མ་རོ་ཟན་མ་ལ་། དམ་པའི་ཞལ་ནས་། རི་འི་བུ་སྐྱེས་[illeg.]། རི་དགས་ལྟར་དམན་བའི་ས་ཟུང་། འདོད་པ་ལྔ་སྤངས་ན་ཚོགས་རྫོགས་། བྱ་བ་བཏང་ན་ཡེ་ཤེས་ཆར་རེ་གསུངས་པས་། མོས་དེ་ལྟར་བྱས་པས་གྲོལ་ལོ་། ཇོ་མོ་འབར་མ་རོ་ཟན་མ་། ཡུལ་སྟམ་པ་མོ་། ་་་ས་[?]ནས་བླང་འཁོར་དུ་བསྡད་། གུ་ཐང་དུ་གྲོངས་སོ་།། ༑ །།

ro zan ma la lung bstan pa / ri'i bu gyis / dman pa'i sa zung / 'dod pa spangs nas tshogs rdzogs / bya ba btang nas ye shes 'char [ZCK 7r] gsung bas mo des grol /

To Barma Rozanma Dampa prophesied, “Be a child of the mountains, but (like the deer) keep a low profile. When you give up (the five) desires, the accumulations are complete, give up the busy life and Full Knowledge will appear.” Doing as he said the woman was liberated. Jomo Barma Rozanma was a woman of Tampa. Later she stayed in Langkhor. She died in Gungthang.

•21•

ཇོ་མོ་ཤངས་ཆུང་མ་ལ་དམ་པའི་ཞལ་ནས་། ང་འི་སྦྲེ་གར་དུ་ཁྱོད་རང་ཅིག་པུ་་་[?]ཕེར་ན་གུད་དུ་ཤོག་། ཞ་ནག་པོ་ཕུད་ལ་ཤོག་། ང་འི་ལས་རྒྱ་བྱའོ་། ཁྱོད་དམ་ཚིག་དང་ལྡན་བ་དྲི་བཟང་པོ་བྱུག་ལ་ཤོག་ཅིག་། གོ་ཅ་བཟང་པོ་སྟན་མྱི་འགྱུར་པའི་གོན་ལ་ཤོག་ཅིག་། ལྷན་ཅིག་སྐྱེས་པའི་ལྟད་མོ་ཅིག་བསྟན་ནོ་གསུང་། མོ་བརྡའ་བདེའ་སྟོང་རྒྱུད་ལ་སྐྱེས དེ་གོ་བས་། ཤངས་ཆུང་མ་ནི་གྲོལ་ལོ་མཁས་སོ་གསུང་། མོ་དེ་ནས་གྲོལ་བ་ཅིག་བྱུང་ངོ་།། ཇོ་མོ་ཤངས་ཆུང་མ་། ཡུལ་ཤངས་པ་མོ་། གྲོངས་པ་ཆ་མྱེད་དོ་།། ༏ །།

shang chung ma la / bla mas gud du khrid de / nga'i skra dkar dkar ba'i chos nang du zha nag po sdig pa phud pa las rgya bya'o // dri bzang po tshul khrims dang byug la shog cig / go cha bzang po gon la shog cig / lhan cig skyes pa'i bltad mo bsten no // mos brda de go bas shangs chung ma grol lo mkhas so gsungs / mo dus de nas grol ba gcig byung ngo //

The Lama took Shangchungma aside and said to her, “Among these white hairs (virtuous Dharma) of mine there is a tuft of black hairs (sin). So be my Karmamudrā. When you come to me anoint yourself with fine scents (keeping the commitments). Dress yourself in fine armor (firm and unwavering) and come to me. Entertain me with a show of coemergence. The woman understood these symbolic expressions (bliss and emptiness united in her mind stream), and he said “Shangchungma is liberated, she is knowledgeable.” Then this woman turned out to be a liberated one after that. Jomo Shangchungma was native to Shangpa Valley. Where she died we do not know.

•22•

[48r from Matho v314]

ཇོ་མོ་ཞ་ཆུང་མས་དམ་པ་ལ་གདམ་ངག་ཅིག་ཞུ་འཚལ་བྱས་པས་། བར་ཆོད་ཁྲག་འཛག་པ་སེལ་། དབང་གི་ཡོན་བླ་མ་རྨ་ལ་ཕུལ་། རྐ་ཐུབ་ཚད་དུ་དམ་བཅའ་སྐྱོལ་བསྡམས་པས་ཐུན་བཞིར་སྲངས་ནས་ཐོན་། དེ་ལྟར་བྱས་ན་ཁྱོད་འབྲུག་གི་སྟ་ལ་ཞོན་ནས་སྒྲ་ཆེན་པོ་ཡོང། ནམ་ཀར་འགྲོ་བར་མཆིའ་སྟོང་ཉིད་དོན་རྟོགས་ནས་གསུང་ངོ་། དེ་ལྟར་བྱས་པས་བླ་མའི་བཀའ་བཞིན་དུ་དེ་ལྟར་བྱུང་ངོ་། ཇོ་མོ་ཞ་ཅུང་མ་རྒྱལ་མོ་སྐྱིད་། ཡུལ་ཕ་དྲུག་མ་། སྒོམ་སྤུབ་དིང་རི་ཤར་ལོགས་བྱས་མཛད་། ཤར་ལོགས་སུ་གྲོངས་སོ་།། ༑ །།

jo mo zha chung mas zhus pas / bar chod sol / rma lo tstsha ba la dbang gi yon phul / dka' thub sgrub pa tshad du skyol / gdams pa'i srang nas thon / de ltar byas na / 'brug gi grags pa 'byung ba'i brda rta zhon / namkha' la 'gro bar gda' gsungs /

After Jomo Zhachungma said to Dampa, “I would like to request a precept,” he said to her, “Clear away the obstacle (dripping drops of blood), offer an empowerment fee (to Lama Ma), conduct the difficult practices (the sādhana) to full measure (vows), weigh the precepts in the balance. If practiced in that way, you will ride on a dragon horse (symbol for her coming renown) and arrive with a roar traveling in space (after realizing the meaning of emptiness).” She did so (in accord with the words of the Lama) and it was just as he said. Jomo Zhachungma Gyelmokyid was native to Padrug. She kept to her meditation cave on the east face of Tingri, and it was on the east face that she died.*

(*If you feel the need to divine the correct sense of this story, you would be well advised to consult Cyrus Stearns, Taking the Result as the Path, Wisdom [Boston 2006], p. 209. The story, never told twice in the same way, is a particularly amazing one.)

•23•

བོ་མ བོ་མོ་གཞོན་ནུ་མ་ཅིག་ལ་། དམ་པས་མོ་འི་མེ་ལོང་སྐ་བསེབ་ནས་བཏོན་ནས་། འདི་ཁྱོད་རང་གི་མེ་ལོང་ཡིན་ནམ་། ཁྱོད་ཀྱིས་མེ་ལོ་ལྟ་ཤེས་སམ་གསུངས་ནས་ཤེས་ཟེར་། ཁྱོད་ཀྱིས་ལྟ་ཤེས་ན་འཇིག་རྟེན་གྱི་བྱ་བ་ལ་ཞེན་པ་ལྡོག་། འཁྲུལ་པ་འཛིན་པ་མྱེད་པ་འཇིག་། ལས་མཛད་བདེའ་བ་རྒྱུད་ལ་ཤུགས་ལ་འབྱུང་། རང་གི་མེ་ལོང་ལ་ལྟ་བ་ཁྱོད་ལས་མྱེད་དོ་གསུངས་པས་།

bu mo gzhon nu ma gcig la dam pas me long skra gseb nas bton[ n]as / 'di khyod rang yi me long yin nam / khyod kyi blta shes sam gsung / mo yi blta shes lags byas pas / lta shes na 'jig rten chos pa zhen pa ldog / rang gi las mdzad / bde ba sems la 'byung / 'khrul pa 'jig / rang gi me long la lta ba khyod las med gsungs pas /

To one young girl, Dampa said, after he pulled her mirror out of her sash, “Is this mirror your possession? Do you know how to look in a mirror?” “Yes, I know,” she said. “If you know how to look in a mirror, reverse attachments (to the busy life of the world), dissolve illusions (not having attachments), perform the rites and enjoyment will emerge in your mind stream (in force). To look in the mirror of yourself, there is no other than yourself.”

བོ་མོ་ལ་དུས་དེར་བྱི་རླབས་ཞུགས་། བརྡའ་དེས་མོ་གྲོལ་ནས་། ཁྱིམ་ཐབ་[erasure]སྤངས་ནས་། སྒོམ་མ་མྱི་བྱེད་ལུས་ཐ་མལ་དུ་ཡོད་། མོ་ངག་བཅད་ནས་སྐུགས་པ་མོར་གྱུར་ཏེ་། སུས་ཀྱང་མ་ཚོར་བར་སྦས་པའི་རྣལ་འབྱོར་མར་ཡོད་གསང་སྤྱོད་མར་ཡོད་དོ་། བོ་མོ་འི་ཡུལ་དིང་རི་ས་མར་ཕུག་མ་། མེ་བུ་དཀོན་གྲགས་གྱི་བོ་མོ་། ཡུལ་ས་དམར་དུ་གྲོངས་སོ་། [48v]

bu mo la byin brlabs zhugs te / brda khrol nas rang grol te / khyim spangs / sgom ma byed / ngag bcad / bsgrub pa mor gyur te sus kyang ma tshor ba gcig byung /

At that moment the blessings entered into the girl. Through this symbolic language she was liberated, and abandoned her household life. She did not live as a hermit (she remained in an ordinary form). She stopped speaking and lived as a mute. Unperceived by anyone she remained in the secret activities (as a hidden yogini). The girl’s home country was Samar Phug in Tingri. She was daughter of Mebu Köndrag. She died in the region of Samar.

•24•

ཉ་མ་ཁྱིམ་པ་མ་ཅིག་གིས་། དམ་པ་ལ་གདམ་ངག་ཅིག་ཞུས་པས་། དམ་པའི་ཞལ་ནས་། ལོང་སྤྱོད་སྒྱུ་མར་ཁྱེར་། བུ་ཁྱོ་ཕྲོད་ནས་སུ་སངས་རྒྱས་དང་འདྲ་བར་འཁུར་། དངོས་པའི་ཆགས་ཞེན་བུ་ཁྱོ་ལ་སོགས་ལ་སྐྱུངས་། མྱི་རྟག་པ་ཡིན་བས་ཤི་ན་མྱི་དགའ་མ་བྱེད་ཞོག་།

nya ma khyim pa mo gcig gis zhus pa la / longs spyod sgyu mar khyer / bu khyo mchod gnas su khur / dngos po la zhen chags bskyungs / shi na mi dga' zhog /

A woman householder disciple requested a precept of Dampa, and the words came from Dampa's mouth, “Take wealth and leisure as illusions. Carry your children and husbands to the cemetery (like a Buddha). Cut down on attachments to things (to children, husbands and the rest). Do not be unhappy with death (as all is impermanent).

ཡོད་པ་རང་དབང་བ་ཐམས་ཅད་ཚོགས་སོག་གིས་། བླ་མ་མཆོད་ནས་དང་པོ་ཐེག་། བྱས་པ་གིས་ཡུལ་མི་སུན་མ་ཕྱུང་། ཉེ་ཐུ་བུ་ཚ་ལ་སོགས་ཆོས་ལ་ཁོད་། ལྟ་བའི་གོ་གོན་ཅིག་ཆོས་བའི་དྲས་ག་[~རལ་ག་?]༡་ཟུང་། ལས་རྒྱུ་འབྲས་ལ་ཡིད་ཆེས་པར་གིས་ཁུར་ཙ་བཟང་པོ་འཁུར་། རྒན་མོ་འཆིའ་ཀར་མ་འགྱོད་ཨང་གསུང་ངོ་།། །།

nor yod pas tshog sogs gyis [ZKC 9v] bla ma mchod gnas thegs / nye du chos la khod / chos pa'i dras kha zung / khur tsa bzang po khur / rgan mo 'chi kar ma 'gyod ang gsungs /

“What you have (what is within your power) make into virtuous accumulations. Elevate (first) the Lama and patronized priest. Don’t excoriate your countrymen (do your work). Establish those close to you in the Dharma (children and the rest). Wear the robe of a Dharma practitioner (put on the armor of the view). Bear the good burden (have confidence in karmic cause and effect). In old age, the moment of death will hold no regret.”

ཇོ་མོ་ཉི་ཤུ་རྩ་བཞི་ལ་བསྡམས་པ་། ཀུན་དགས་ཡི་གེར་བཀོད་པ་། ཇོ་མོ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་ཞལ་ནས་བླས་པ་དང་གམ་དུ་བསྟད་པ་ཆ་འདོད་པ་(~དོད་པ་)། གཞན་རྐྱེན་གྱི་བསྡམས་པ་།། རྫོགས་སོ།། ༑ །།*

rje btsun dam pa rgya gar gyis / jo mo rnams la gdams pa'i chos skor rdzogs.ho // zhuso | dge'o // shu wam //

Precepts for the Twenty-four Jomo, put into letters by Kunga. I have given fragments from what was relayed to me by the Jomos and from sitting by their side. These are other occasioned (gzhan rkyen) precepts.

[*I leave off the two lines that end the Matho version, as it is made up mostly of mantras that may have been placed there for protective purposes although this is unclear. The letters appear to be just as pre-13th century as the rest.]

§ § §

A SIDE ISSUE

What is the meaning of other occasioned (gzhan rkyen)? It appears not only at the end of the Matho version, but also in the title of the same (but not identical) text as found in ZCK. Padampa had two types of precepts, the ones occasioned by others (gzhan rkyen) and occasioned by himself (rang rkyen). Occasioned by others means that the precepts were aimed toward particular disciples, taking into account the ways they view their world, and thereby tailored for their special needs. Occasioned by himself would include raw and unfiltered words spontaneously pouring out from his mouth to suit the occasion.*

(*A BDRC search turned up this Zhijé definition: de la rje dam pa sangs rgyas rin po ches gsungs pa'i gdams ngag ji snyed pa rnams/_rang rkyen dang gzhan rkyen rnam pa gnyis su 'dus/_gzhan rkyen ni gang zag gi yul lta mkhyen pas/_pha rol nang gi nyer len gyi steng du btabs pa rnams so/_/rang rkyen ni snying gtam me btsar btabs pa ste/_skabs la babs pa'i zhal ta thol smras kyi brjen gtam rnams so/_/'di rang rkyen las kyang snyan rgyud 'phrul tshig lag len gyi skor/_ This is from vol. 3 of the title Zhi-byed Snga Phyi Bar Gsum-gyi Chos-skor Phyogs-bsgrigs. No page no. can be given because the page correspondences are not supplied by BDRC. But wait, it ought to be on p. 452, so let me go check to be sure.)

If you just consider the examples from the Matho, you can see that not every woman is assumed to share the same religio-spiritual aims. Padampa is just as comfortable giving advice for achieving a better rebirth as for achieving Buddhahood in one lifetime.

+ + +

Sources on Jomo Penmo (no. 18)

Limiting ourselves to the first one in the translated section, I thought you may be curious to compare Jomo Penmo’s entry in the long-available Blue Annals, p. 919:

“The lady ’Phan-mo: her native place was ’Phan-yul. She lived with one attendant at gLaṅ-’khor (near Diṅ-ri), and both died at the same time. (At the time of her death) the valley was filled with medicated perfume (sman-dri) and many auspicious signs were observed. All were filled with wonder.”*

(*The Tibetan of the Deb-ther Sngon-po, in transliteration, reads so: + jo mo 'phan mo ni / yul 'phan yul / mo rang dang nye gnas ma gnyis glang 'khor du bzhugs nas mnyam du grongs pas lung pa sman drir song / rtags bzang po mang po byung nas thams cad ngo mtshar skyes so.)

Passage on Penmo from the collection of precepts

In Jo-mo Nyi-shu-rtsa-bzhi'i Zhu-lan Lor-rgyus dang bcas-pa, containing two different texts, one on the precepts and the other on the lives. The one on the precepts as contained in ZC, vol. 4, p. 302 up to the end of p. 313, at p. 311, line 4:

jo mo 'phan mos zhus pa / rtog pa myed pa la nad 'dre yi nyam nga dang / bag tsha yod de / tshogs sog pa la dga' na yo byad kyis myi 'bor cig / khyod sman ma 'tshong / chang ma nyo / snang ba la kha phyir ma btang / rang la ma stod / gzhan la ma smod / ting nge 'dzin la kha'i bya sgrog gzhag / gsol ba thob / phyi ma la don grub ste 'ong gsung / pha pad mos zhus pa spyad rgyu yi tshogs gsog pa myed / dbus su phyin na dam pa dang 'bral / bdag gis ji lar bgyi zhus pas / bla sa nas za ba ra rdzi rgyal po yin / 'tsho ba nam ka'i dbyings nas sbyor / [311] mdzod de di ri sdong na yod / sgrub pa mo la phyag tsang mkha' 'gro sde bzhis byed / gzad dpon nag po a tsa ra / der 'phags chos / zas gos phyid cing yon tan du shar ro //

Passage on Penmo from the collective biography

The following is her entry from the collective biography put in writing by Kunga in ZC, vol. 4, pp. 314-323, starting at p. 320, line 4:

bcwa brgyad pa jo mo 'phan mo ni / yul dbu ru 'phan yul ma yin / shin tu dgeg la gsol ba cig yin / dkon mchog mchod pa la mkhas shing brtson ba / spos sbyor ba la rem bas / bal 'khams kyi tshog pa sman 'bul ba mang po 'ong / mo dang nye gnas ma gnyis kas lo du ma glang 'khor du [321] bzhugs nas / de rang du mnyam du grongs pas lung pa sman dri ru song / rtags bzang po mang po byung ste / thams cad ngo mtshar skyes so.

It is this passage that is translated in Gianotti’s book, p. 131.

It’s clear that the Blue Annals author took the liberty to even further abbreviate the version in the ZC's collective biography, and made use of nothing from the collections of precepts.

•

IF you see for yourself a future in the study of Tibetan women’s history as much as I hope you will, you may be interested in a searchable file with names of Padampa’s women disciples (indexing their appearances in five different texts exclusively devoted to them so they may be located with ease). It has been placed in “New Tibetological” website on the understanding that if it is there it is more likely to be indexed (and thereby made available to search engines*). Here is the URL:

https://sites.google.com/view/newtibetological/women-disciples-of-padampa

Feel free to copy-paste or save it to your desktop for future reference.

(*As we speak, Google in particular is being surrendered to the control of inhuman AI entities — I think of them as the new archons — who mess things up at least as much as we humans do, just in oddly and awkwardly different ways.)