Today’s blog is a guest blog by Jean-Luc Achard. It was written in response to the immediately preceding blog, “Turtle in a Bronze Basin.”

The image of the turtle in a bronze basin is quite frequent in Dzogchen texts. For instance, it appears twice in the Zhangzhung Oral Transmission, although illustrating different issues or stages occurring during practice. First, in the mNyam bzhag sgom pa’i lag len, it says:

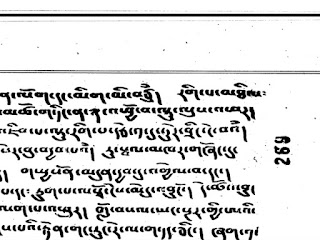

/rnam rtog ’phro rgod mang pa la/ /rus sbal mkhar gzhong bzhag ltar bcos/

“When you have too many scattered and agitated thoughts,

Correct that like placing a turtle in a bronze basin.”

(*This is from the “main” practice work of the 1st section of the Zhang zhung snyan rgyud concerning “general sections on the View” [lta ba spyi gcod]. I used the Triten Norbutse edition published ca. 2000 or 2002, at p. 344).

bzhi pa rus sbal mkhar gzhong tshud pa ’dra zhes pas/ snang ba rdzogs (756) pa’i dus su/ thugs rje’i nyag thag de g.yo ’gul med par gnas pa’o/

“It is said: ‘Fourthly, they* are similar to a tortoise placed in a bronze basin.’ This means that at the time of the perfection of the visions** the chains of Compassion remain without moving and quivering.”***

(*The third verse shows that this refers to the chains of Compassion (thugs rje nyag thag). **This is the fourth vision of Thögel in the scheme of five visions [snang ba lnga] according to the Zhangzhung Oral Transmission. ***gZer bu’i nyer gcig gi ’grel pa, p. 755.)

dang po bon nyid mngon sum gyi dus na/ lus rus sbal mkhar gzhong du bcug pa ltar song ba ni rtsa dal bar gnas pa las 'byung ste/ rdzogs pa chen po byed pa dang bral ba'i gzer lus kyi yan lag thebs pa'i byed pa rang sar dag nas byed pa med pa'i ye shes rang byung du shar ba'o/“First, at the time of the Vision of Manifest Reality, the fact that the body becomes like (that of) a turtle placed in a bronze basin (implying its immobility) results from leaving the channels at ease: the seal of non-action characterizing Dzogchen is applied on the limbs of the body (so that with the latter) being naturally purified, the Wisdom of non-action arises in a self-occurring manner.”

— View (lta ba) is associated with the Garuda (khyung)— Conduct (spyod pa) is associated with the lion (seng ge)— Samaya (dam tshig) is associated with the swan (ngang mo)— Activities (phrin las) are associated with the cuckoo (khu byug), and— Meditation (sgom pa) is associated with the turtle (rus sbal).

sgom pa ni rus sbal rgya mtshor bskums pa ltar bshad de/ rnam rtog gis g.yo ba med par rang gsal du gnas par bstan pa'o“Meditation is explained to be like a turtle contracting (its limbs) in the ocean, illustrating the fact that one should remain (absorbed) within one’s natural Clarity, without being moved/affected by discursive thoughts.”

rus sbal bskum thabs kyi dgongs pa zhes bya ba/ sems nyid ye nas g.yo ba med cing ma bcos pa gnas pas/ reg pa dang rkyen gyi tshor ba las 'byung ba'i mtshan ma thams cad 'jom pa'o/

“The so-called ‘Contemplation on the turtle’s manner of contracting (its limbs)’ means that since Mind itself primordially abides without movement and without contrivance, all characteristics arising from contacts and conditioned sensations are subdued.”

This means that once this stage of stable contemplation is achieved, one remains naturally in the immutable and non-artificial nature of one’s Mind, just like a turtle naturally retracts its limbs and remains immobile when placed inside a small basin. At that stage, one subjugates any kind of characteristics associated with sensations, contacts, etc., because nothing can actually distract us anymore from one’s contemplative experience.

The tortoise in a small basin and the tortoise retracting its limb are images that one also finds in Nyingma works on Dzogchen (more the first than the second by the way), such as the sGra thal ’gyur commentary (associating the immobility of the turtle to that of the body), the mKha’ ’gro yang tig, etc., down to 20th century works (for instance, in at least one of Dudjom Rinpoche’s works, one of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s composition, etc.). Further examples could be given.

Response to Jean-Luc (May 28, 2024)

Dan: Many thanks for sharing so much knowledge, much of it entirely new to me. I am particularly intrigued by the presence of the metaphorical turtle in the Gab-pa, and feel inclined to look into it more before long.

With all these additional Bon examples, it seems all the more clear that already in the 11th and 12th centuries, three discrete Tibetan traditions — the Bon, Nyingma and Zhijé — were sharing the same four-syllable expression that means ‘turtle in a bronze basin.’ At the same time, it isn’t at all obvious that they mean exactly the same thing by it. The differences may in part be contextual, they may be employing it in different teaching situations. They do share one broadly similar idea, that something or another is, despite itself, getting locked into place and immobilized. The Bon Dzogchen examples are surely looking quite different from the Zhijé in their way of explaining it.

As I personally tend to understand it, the turtle, with its unusual ability to pull its legs as well as its head into its shell, is a natural symbol for the withdrawal of the five senses in meditation, the attention fully internalized. I know of no clear or direct Buddhist or Tibetan justification for this idea in my head. The best I can come up with is a verse from the Bhagavad Gita (ch. 2, v. 58):

“When like the tortoise which withdraws on all sides its limbs, a man of perfection withdraws his senses at will from sense objects, then his wisdom becomes steady.”

However, in my Zhijé examples the situation is different, the turtle in the bronze basin does have its head and limbs out (in my understanding, its senses are "out there," aware of external phenomenon) even while its body as a whole is immobilized. It is calm but alert, enjoying the light of the sun, basking in it.

§ § § § §

Jean-Luc’s response (May 28, 2024)

In the Dzogchen sources that I have access to, the turtle in the basin is a metaphor for the immobility of the body but also, as shown above, a very rare reference to the stability of the visions arising during Thögel practice. But, certainly, it seems clear that in other contexts, such as in the Zhijé teachings, it definitely seems to refer to the senses. Your quote from the Gita is in this respect very interesting in this regard. That’s a fascinating find!

As the image was explained by Yongdzin Rinpoche, in the Bön sources that he used and where the expression occurs, it strictly points to the fact that when placed in a small basin a turtle contracts its limbs and head quasi-automatically because it cannot move due the size of the basin itself. In fact, the image is used to illustrate a sign (rtags). Thus, in chapter 16 of Ratna Lingpa’s Tantra of the Abyssal Clarity (Klong gsal gyi rgyud) for instance, it is explained that this image with the turtle is actually a sign that appears during the first vision of Thögel, the Vision of Manifest Reality (chos nyid mngon gsum gyi snang ba). Each of the four visions of Thögel has three signs (one for each of the three doors). Thus, during the Vision of Manifest Reality :

“ — As for the body, it remains without activities,

Like a turtle placed in a bronze basin.”

(lus ni bya byed me pa ru/ ru sbal mkhar gzhong bcug pa ‘dra/).

This is actually the result of the temporary dissolution of the wind of the earth element in the body. At that time, one feels like an immobile statue and prefers not to move at all. Of course, this is especially true during formal sessions. However, even during post-obtainment (rjes thob), the wind of the earth element can temporarily resorb itself, particularly when one just rests, sitting while doing nothing in particular. This means that its dynamism (rtsal) has entered a year-long process of gradually reaching its exhaustion (like the other elemental winds).

Furthermore, at the beginning of the Gab pa, you’ll find the following reference to the turtle:

|ston pa thugs rje che mnga' ba| |thams cad mkhyen pas de bzhin gsungs| |de las rig pa thabs kyis brgyud| |skal ldan snod bzang 'ga' tsam la| |sems kyi dkyil du phog par bya| |rus sbal rgya mtshor bskums pa bzhin| |phal gyis mthong bar mi 'gyur te| |'di ni gsang ba'i gsang ba'o|

Here it is not associated with the immobility of the body or the senses but rather with the idea of a turtle contracting its limbs in the depths of the ocean and therefore being invisible to ordinary people. It thus illustrates the “secret of the secret”, i.e., the natural state that abides within all beings without the latter being conscious of it.

In the Gab pa rgya cher bshad pa, the line rus sbal rgya mtshor bskum pa bzhin is glossed as follows :

| rus sbal rgya mtsho= zhes pas| dper na rus sbal zhes bya ba'i sems can cig rgya mtsho'i gting na bskums nas 'dug pa de| sus kyang mi mthong ba dang 'dra ste| man ngag 'di yang kun gzhi ma g.yos pa'i klong rgya mtsho dang 'dra ba'i dbyings su| rig pa'i ye shes rus sbal bskum pa bzhin zhog cing...

So it points to an animal lying in the depths of the ocean, with its limbs contracted (bskums) so that it cannot be seen by anybody. The precept (man ngag) that uses this illustration actually means that within the immutable expanse of the Universal Base, the Wisdom of Awareness remains hidden like a turtle in the depths of the ocean... (until it is caused to arise by applying special key points). So this is still another usage of the turtle image.