So here is my fast attempt to elaborate on the meanings of every last detail in this surprisingly complex picture. First of all, look on the Old Man’s right hand and see how he holds a pitcher or ewer in the act of pouring out a ritual libation into a small stemmed goblet that rests on top of a larger bowl in its turn placed on an altar table. The larger bowl is there to catch the overflow from the goblet. The overflow itself conveys a notion of copious overabundance.

|

Another, more lightly printed, example of a verso of the 100 srang banknote |

Some may imagine it to be a ‘secular’ scene of an old man pouring himself a drink, but no, nothing could be further from the truth. The elaborate ritual setup indicates a normative practice of Tibetan Buddhism — some people, be they male or female, monastic or lay, perform it every morning. This relatively simple ritual, usually called Water Casting (ཆུ་གཏོར་, ཆབ་གཏོར་, or མཆོད་གཏོར་), involves the pouring of the liquid accompanied by prayers for the pretas, or “hungry ghosts.” Not only was it performed by the earliest Kadampas, but by Bonpos even before them. This practice is supposed to be done out of compassion for those unfortunate beings known as pretas, unable to eat or drink on their own, since it all turns to fire in their mouths. Not incidentally, the practice develops Buddhist merit* and compassion in the person who performs it. One significant further point: Even if the word yidag / ཡི་དྭགས་ generally used for preta is employed here, the objects of compassion are widened to include other large classes of spirit beings, even including the spirits of the dead.

(*I hope to devote some writing to Buddhist ideas about merit another time, but at the moment, do remember that it is one of the two legs that permit advancement on the Path to Enlightenment in Great Vehicle Buddhism. As one of the Two Accummulations, it cannot just be tossed aside in favor of intellectualism or meditation as our 21st-century neo-Buddhists so often try to do.)

Now move directly above the altar and what you will see is a

bat flying in the sky, swooping toward a fruiting tree. It is known that some kinds of bats feed off of fruits. I regard that fact as irrelevant to our reading of the tableau. Their close proximity in the picture is accidental. My reason for thinking so: It’s well known that the bat as a positive cultural symbol is owed to a pun in Chinese. The Chinese word for ‘bat,’ “蝠” (fú) sounds exactly the same as the word for ‘good fortune,’ and ‘wealth’ “福” (fú), and you can see an obvious similarity in the characters as well.* This pun explains why you can see artistic representations of bats all over the place in Chinese households, not just in temples.

(*Look here for an amusing analysis of the parts that make up the character.)

You also see here a

cloth article that looks like a scarf draped over the tree limb. I had to think long and hard about this one. Of course it may or may not be a Tibetan

khata. Although difficult to be certain, it actually seems to be a Mongolian contribution to the iconography. Still, it does remind us of Arhat portraits (based in the

Vinaya Sūtra, and meant to illustrate it, I believe) in which a part of the clothing is just being left on a nearby limb to dry. Like the tableaus I describe here, these Arhat scenes are often painted on the walls of the monastery on the outside... Hmmm, this sounds like the beginning of a theory that would explain the placement of those tableaus...

But then again, it may be in some way associated with the scarf in the iconography of ’O-de-gung-rgyal (and similar long-life deities with varied names) explained by Toni Huber in his book Source of Life (vol. 1, p. 84). Let me quote it at some length:

“The white silk pennant or scarf they hold encodes a dual symbolism that expresses the transfer of life powers between cosmic realms. One of its aspects is g.yang,* and such scarves are sometimes referred to as g.yang dar, while the other aspect of the white scarf is a symbol of the messenger, of something pure and important passing between agents. For these reasons the white scarf is closely associated with the messenger bat...”

(*My note: On g.yang as a culture-specific concept, look here.)

Given the great distances and cultural differences involved, it is rather impressive that the conceptual pairing of scarf and bat that we see in our tableau would show up in remote areas of eastern Bhutan in contexts that are regarded as inestimably archaic and local.

Some people see pomegranates or persimmons, but I believe this is a peach tree. These are the peaches of immortality, well known from very early Chinese ideas about the Queen Mother of the West (Xiwangmu) who used to preside over peach feasts with the immortals of her court in a place often identified with the Kunlun Mountains. While these relatively low mountains form the natural northern border of the Tibetan Plateau, they don’t seem to be known to Tibetan literature. Even so, in Chinese myth and literature (and now film) they have assumed a towering importance. I suppose the immortals were already as immortal as they could ever hope to be, yet the peaches were said to confer longevity if not immortality.

Now we continue circumambulating in the Bon direction, with the left hand oriented toward the central figure. Passing over a cloud-and-mountain-with-waterfall landscape we next encounter a pair of dancing cranes. Pairs of cranes remain lifelong lovers, but they are also amazingly long-lived. Chinese sources have sometimes attributed to them lifespans as long as a thousand years. I like to imagine, as one who has seen for himself how inspiringly and effortlessly they soar in slow spirals upward into the sky, taking advantage of thermal updrafts, that something about that is in there, too. They make migration look too easy.

Next in our leftward turn is what would seem to be an arrangement of offerings related to the libation ritual directly above it. This may well be the case, but close inspection tells me the basin is filled with peaches with their leaves still attached. Do you see something else?

I think the deer couple appears clearly enough for everyone to recognize, but what is that thing off to the side? One of the deer seems to be turning its head toward it. It looks like a plant, but a plant with some kind of bulbous growth in the center. This would be a lingzhi fungus. Sometimes, even if not here, the lingzhi is depicted as if it were growing out of the deer’s head. In Chinese lore, these deer are sort of like the pigs that are used to sniff out truffles in France. The mushroom hunters would never be able to find the lingzhi without the help of the deer, since to every other creature they are invisible.

You can see a few more lingzhi fungi here, but what I want to point out right now is the rocky cavern with the stream of water descending from it. I did have trouble putting my finger on this exactly, but I was imagining it reflects Chinese landscape ideas. Artistically speaking it seems obvious. What we see here bears meanings situated between, or is perhaps shared by, fengshui geomancy and ideals of Chinese landscape painting. When I looked into it further, I thought the landscape feature might be the one known as “shan shui” (dragon/mountain + descending stream). Still, a cave with a water source inside of it has a special name in Chinese that is, as a matter of convention, translated as “grotto.”

Now look a little to your left. You can see a row of blossoms leading diagonally to a more distant grotto that I think, with good reason, would indicate the

Peach Blossom Grotto, a kind of bucolic Shangri-la of the Daoists. We do have the close proximity of the peaches and the grottos, so we may be justified in putting two and three together like this. There is a long and rich history of the Peach Blossom Grotto in China and a number of Sinological essays are devoted to it. It is a place very difficult if not impossible to find, but going there would mean encountering the immortals.

Now for the main figure of the White Old Man itself: First observe the smaller human seated on a mat of grass to his left side. Sometimes this is called an “acolyte figure,” as if it were a child assistant in a Catholic mass, procession or the like. I see no reason to speak Catholic here, so I would suggest the youth depicted here represents 'youth,' or or maybe even rejuvenation. The youth seems to hold something up in one hand, but I am unable to make out what it is. Alternatively or at the same time, he may serve as an attendant, an errand boy.

The Old Man’s very corpulence is a sign of opulence. His right hand holds the ritual ewer, in his left a rosary. The ewer we have mentioned already, but the rosary is evidently a māla used as support for mantra recitations, a constant occupation of many Tibetan elders. He has a beard, no doubt very white.

There is one interesting thing, among others, that is not visible here. We might think he needs to have a staff inside the crook of his left elbow. The staff might end, as the texts describe and prescribe in a knob or handle in the shape of a dragon. But not here, which is remarkable since it would seem to be one of the few constants according to the Sūtra and texts associated with it. More on these texts presently.

Now let’s leave the money behind for a few minutes and have a quick glance at the literary sources, especially as these have bearing on the iconography.

Here above, you see the opening lines of the White Old Man Sūtra, in Sanj Altan’s translation from the Oirat version. Pay special attention to the iconographical information in lines 10-12. This text is sometimes called by that just-given title, but also The Sūtra of the Power to Keep within Bounds the Earth and Water. The titles you see below.

Both of the texts you see here are from the collection of the Mongolian National Library (Ulan Bator). Both are scans done by agreement with the BDRC. I think we can safely say that these Tibetan texts are local Mongolian products, and that versions of it might not even exist on the Tibetan plateau (we need to demonstrate local Tibetan interest rather than assume it, since Mongolian monks did compose and scribe Tibetan texts for their own use). One interesting thing is that the title is given first in Chinese, which would suggest that the original text was in that language. Still, I do not know of any Chinese version of it existing today (I may very well require correction on this point), and believe that this apocryphal scripture was made in Mongolia, very likely by a monk who knew Tibetan language as they very often did, in order to accommodate the local cult of the White Old Man within a Buddhist context.

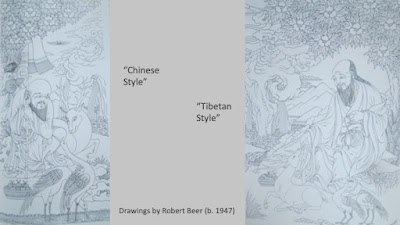

An outstandingly talented artist, Robert Beer supplies two versions of the Old Man in his book, yet it is only the one labeled as "Tibetan style" that is based on an earlier painting done by a Tibetan, while it appears that the "Chinese style" he created by combining various elements he thought to be Chinese, many of them indeed associated with immortals and with the Old Man of Chinese lore called Shouxing (Shou Hsing). It’s interesting that he is depicted with an antlered deer, this being his usual mount, a dragon-headed staff,* and a gourd. Why is the gourd there at the top of the staff? That question leads us into amazing territory nicely surveyed by R.A. Stein in his book, a book I much recommend. The gourd was used by Chinese herbalists to contain the herbs they collected in the mountains. It also served for Daoists as a container for a miniature world that immortals could physically enter into by miniaturizing themselves. It is basically equivalent to the grotto, both gourd and grotto being a normally unseen interior world, perhaps in miniature; both are populated by hermits or refugees from the busy world, and they have skies of their own, no matter how difficult that may be to think about... Oh, and the staff ought to be craggy and a little crooked, resembling a gnarly pine tree limb, if it is to be associated with Chinese immortals. Not the smooth cane we see here. In sum, I would have composed the picture of the "Chinese style" a little differently than Beer did.

(*The dragon head on the staff might seem to indicate Chinese origins, but I believe it to be a Mongolian contribution to the iconography of the White Old Man. Of course it requires further consideration. I am not especially clear what Beer meant by "Chinese style." He might be talking about actually artistic practice in China, but on the other hand he might intend a conscious artistic choice made by a Tibetan artist to produce a Chinese-inspired painting... )

I’m not going to go into the very relevant question of when the Mongolian White Old Man entered into Tibetan monastic dances called Cham (འཆམ་). The common wisdom is that the 13th Dalai Lama introduced it, inspired by a performance he witnessed during his time in Mongolia in the early 20th century. (I haven’t been able to trace a Tibetan-language source on this yet.) It’s interesting to see how Cham dances done in different Himalayan communities identify the same figure as either the Chinese Hoshang, or as the White Old Man. I can’t sort that out right now, but it is fascinating and merits reflection. In Tibetan Cham he tends to have a comic role, in that he attempts to perform simple lay Buddhist practices like khata offerings and prostrations and fails miserably. Or should we say hilariously?

I did my best for the time being to locate earlier testimonies for the White Old Man in Tibetan history, and by far the most interesting thing I could come up with is an 18th century verse by a well-known author of eastern Tibet.

The Six of Long Life,

by Zhuchen Tsultrim Rinchen (1697-1774)

On the author, see the biographical sketch by Benjamin Nourse at Treasury of Lives.

སྔོན་དུས་མ་ཧཱ་ཙི་ནའི་ཡུལ་གྲུ་ན།།

བསྐལ་པ་ཆགས་པའི་ཐོག་མར་བྱུང་བའི་བྲག།

མཐོ་མཛེས་དྲུང་གི་དབེན་གནས་ཉམས་དགའ་རུ།།

འཆི་མེད་མགོན་པོ་གྲུབ་པའི་དྲང་སྲོང་བྱུང་།།

In an era long gone by, in the region of Mahācīna,

was a rock that emerged at the dawn of the eon's formation.

Close by its lofty splendor, in a pleasant retreat place,

appeared an accomplished sage, a master of immortality.

དེ་མཐུས་བྲག་རི་དེ་ཡི་འགྲམ་པ་ནས།།

རྒ་ཤི་མེད་པའི་བཅུད་ལེན་ཚེ་ཡི་ཆུ།།

རྟག་པར་བབ་ཅིང་མྱ་ངན་མེད་པའི་ཤིང་།།

མེ་ཏོག་འབྲས་བུས་ལྕི་བ་ཞིག་ཀྱང་སྐྱེས།།

Through his magical powers at the side of that rocky mountain appeared

a spring of life with alchemical powers to do away with old age and death.

It flowed down unceasingly and there as well was an Ashoka [non-suffering] tree

heavily weighted down with flowers and fruits.

དྲང་སྲོང་དེ་ཡི་བྱམས་པའི་ར་བ་ན།།

ཟང་ཟིང་མི་འཇིགས་སྦྱིན་པའི་གཡབ་མོ་ཡིས།།

འཁོར་དུ་བོས་པའི་འདབ་ཆགས་སྤུ་སྡུག་དང་།།

རི་དགས་རུ་རུ་གནས་པའང་ཚེ་རིང་གྱུར།།

Fast within the corral of that sage's affection

were the soft downed birds, their birdsongs all around,

and dwelling with them the Ruru deer.

With a wave of his hand he grants them fearlessness and food.

དེ་དག་རྒ་ཤི་སྤངས་པའི་བདེ་བ་ལ།།

རེག་པ་གང་ཕྱིར་ཚེ་རིང་རྣམ་དྲུག་ཅེས།།

གྲགས་པའི་འཕྲིན་ཡིག་ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་དགའ་མ་ཡི།།

མཁུར་ཚོས་རྣམ་པར་མཛེས་པའི་རྒྱན་དུ་བྱིན།།

Together these are known as the Six of Long Life who serve

for attaining to the comfort of being done with old age and death.

This announcement letter is offered as an ornament to beautify

the cheeks of the gladdening women of the compass directions.*

(*Note: Zhuchen liked to use the image of “the cheeks of the gladdening women” in other contexts, and I believe these are all alluding to the messenger poems, an Indic literary genre, its most famous example being Kālidāsa's Cloud Messenger. I should add in order to forestall predictable reactions, that the ‘Indianization’ of particular elements in the poem — the tree identified as Ashoka tree, the deer as a ruru deer, for examples — reflects the strong impulse within Tibet's own traditions of kāvya poetry to Indianize whenever possible for artistic/aesthetic reasons. This is •not• an example of Buddhist ‘appropriation’ along the lines you might be thinking.)

As I said already, his iconographic white color bears no connection to skin color or race. It’s the color of his hair if he has any and beard, and/or his clothing. This iconographic whiteness is something he holds in common with the primary ancestral divinity (with varied names and guises including one we mentioned already) associated with the rites of bringing down life that Toni Huber explored so thoroughly in his recent two-volume book. His tunic, scarf, horse, deer, bird etc. are all said to be white (pp. 83-84). Of course there are a lot of observations about details such as these that might be pointed out (the bat for another surprising instance).

Mongolists mostly have faith in the idea that today’s White Old Man is an adapted form of an ancient, natively Mongol shamanic complex. Still, Chinese origins for much of his iconography is relatively clear, while one academic, Brian Baumann, deserves attention for his arguments in favor of Indic priority in the form of the sage Agastya, often identified with the bright but seldom seen southern star Canopus. And for those who can’t imagine that Tibet could possibly be a place of origins, I’d ask them to read Toni Huber’s book I mentioned before.

If made to decide what the main point of it all ought to be, I think it is this: The inter-national, inter-cultural dimensions of the cult of longevity as we find instanced in so many parts of eastern Eurasia has had very complex interconnections reaching far back into the haze of prehistory. So far back I’m convinced we will never be able to single out a single culture as the one that best exemplifies it, or that would preserve it in its most pristine forms. As usual, I think reflections about possibilities can be more productive than closing off discussion with a conclusion. Now that it’s so close to lunchtime, might I suggest as starter the sautéed mushrooms? The lingzhi if you can find them.

Reading list

Fred Adelman, “The American Kalmyks,” Expedition, vol. 3, no. 4 (1961), pp. 26-33, with photographs by Carleton S. Coon. There is also a digital version of it.

Sanj Altan, “An Oirad-Kalmyk Version of the ‘White Old Man’ Sūtra found among the Archives of the Late Lama Sanji Rabga Möngke Bakši,” Mongolian Studies, vol. 29 (2007), pp. 13-26. This includes a translation of an Oirat Mongolian text, preserved within the Kalmuck community in Philadelphia, of the apocryphal sūtra listed below as Tibetan text no. 4.

Barbara Mary

Annan, “Persistence and Renewal of Worship of the White Old Man in Western Mongolia: An Independent Folklore Research Project in Collaboration with Dr. Balchig Katuu.” The great value of this 16-page essay (including photos) is that it recounts a number of stories told from life about the persistence of Old White Man related beliefs among modern Mongolians, particularly those in the western regions. Available at

academia.edu.

Anonymous, “Buddhists Build Their Own Church,” Life, no. 33 (November 10, 1952), pp. 97-98.

Although I don’t know on what basis, it is sometimes said that peach trees were first domesticated, which is to say grown in orchards, on the slopes of the Kunlun Mountains, and if this is so it may serve as a kind of vindication of the Chinese myths. What is more certain is that the domestication of the peach took place in the general area of China (which specific spot it is difficult to determine).

Richard M. Barnhart, Peach Blossom Spring: Gardens and Flowers in Chinese Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York 1983). A gorgeously illustrated exhibition catalog on pre-18th-century paintings of garden scenes, with well written and evocative essays as well.

Brian Baumann, “The Legend of Mother Tārā the Green,” contained in: Vesna A. Wallace, ed., Sources of Mongolian Buddhism, Oxford University Press (Oxford 2020), pp. 361-382. On p. 363:

“The White Ṛṣi in question is obviously a foreign deity in the Mongolian tradition that originated in Hindu Brāhmaṇism. There ‘White Ṛṣi’ is an epithet for the deity Agastya, personification of the star Canopus. It so happens that the White Old Man the White Ṛṣi turns into is a personification of the exact same star only in Chinese Daoist tradition. The text therefore appears to allude to the assimilation of Chinese Canopus allegory from heterodox Daoism into the Mongolian Buddhist pantheon, an act which appears to have taken place sometime in the mid eighteenth century. Shamanism is a synthetic ontology invented by Western scholars and ascribed to the Mongols irrespective of historical reality. The Legend of Green Tārā has nothing to do with it whatsoever.”

Brian Baumann, “The White Old Man.” Paper given in Berkeley (2017). Video on YouTube.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/P58N1zGrc1M" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Brian Baumann, “The White Old Man: Géluk-Mongolian Canopus Allegory and the Existence of God,” Central Asiatic Journal, vol. 62, no. 1 (2019), pp. 35-68.

Robert Beer, “Narrative Illustrations,” Chapter 4 in: The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs, Serindia (London 1999), pp. 94-100.

What he calls narrative illustrations I call tableaus. The modern British artist supplies a Chinese style grouping called Shou-Lao, or the Six Symbols of Longevity (plate 58), as well as a Tibetan-style group he calls by the same name (plate 59). In both case he identifies the fruits as peaches. He says the Tibetan-style version is patterned after a drawing by the modern Tibetan Tsering Wangchub (Wangchug?) of Tashijong. It seems that the Chinese version is the British artist’s own creation, combining various elements perceived as being Chinese.

Wolfgang Bertsch, A Study of Tibetan Paper Money with a Critical Bibliography, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (Dharamsala 1997).

This publication is a serious analytical study, the best I know about, and it doesn’t give indications of values given to banknotes by collectors. I understand that the 50-srang notes are actually much more valuable to them than the 100, counterintuitive as that may seem. Both have the Long-Life Man design on their versos.

Raoul Birnbaum, “Secret Halls of the Mountain Lords: The Caves of Wu-t'ai shan,” Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, vol. 5 (1989-1990), pp. 15-140.

Àgnes Birtalan, “Ritual Texts Dedicated to the White Old Man with Examples from the Classical Mongolian and Oirat (Clear Script) Textual Corpora,” contained in: Vesna A. Wallace, ed., Sources of Mongolian Buddhism, Oxford University Press (Oxford 2020), pp. 270-293. The same author wrote an essay, “Cagān Öwgön – The White Old Man in the Leder Collections The Textual and Iconographic Tradition of the Cult of the White Old Man among the Mongols,” although I haven’t gotten access to it.

Stephen R. Bokenkamp, “The Peach Flower Font and the Grotto Passage,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 106, no. 1 (1986), pp. 65-77.

Suzanne E. Cahill, Transcendence & Divine Passion: The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China, Stanford University Press (Stanford 1993). I think everyone agrees this is the best source available in English about the Queen Mother of the West and her residences.

Barbara Gerke, Long Lives and Untimely Deaths: Life-Span Concepts and Longevity Practices among Tibetans in the Darjeeling Hills, India, Brill (Leiden 2012).

Walther Heissig, The Religions of Mongolia, tr. by Geoffrey Samuel from the German edition of 1970, Routledge & Kegan Paul (London 1980), pp. 76-81. At p. 76 you can see how Tibetan rgan, ‘elder,’ and sgam, ‘wise clever,’ get crossed somehow:

“The Mongols worship under the name of Tsaghan Ebügen (White Old Man) a deity of the herds and of fertility, who is also present with the same form of manifestation and the same functions among the Tibetans (sGam po dkar po)* and the Na-khi tribes of South-West China (Muan-llū-ddu-ndzi), and to whom East Asian parallels can be found in the Chinese Hwa-shang, Pu-tai Hoshang and the Japanese Jurojin, and a European parallel in the form of the bearded St. Nicholas. This is an instance of the veneration of the ‘Old Man’ as a personification of the creative principle.”

(*My note: Observe how the Tibetan spelling meaning “White Wise [Man]” is given rather than the spelling that means ‘White Old Man,’ but this confusion of near homonyms appears to be endemic, and may be indicative, which is not to say that old always means wise. In his iconography he is often characterized by a dragon-headed staff that Heissig understands as the shaman’s staff.)

Futaki Hiroshi, “Classification of Texts Related to the White Old Man,” contained in: H. Futaki & B. Oyunbilig, eds., Questiones Mongolorum Disputatae, Association for International Studies of Mongolian Culture (Tokyo 2005), pp. 35-46.

Toni Huber, “An Obscure Word for ‘Ancestral Deity’ in Some East Bodish and Neighbouring Himalayan Languages & Qiang Ethnographic Records towards a Hypothesis,” contained in: Mark W. Post, et al., eds., Language & Culture in Northeast India & Beyond in Honor of Robbins Burling, Asia-Pacific Linguistics (Canberra 2015), pp. 162-181.

On a curious name for the clan ancester deity: Gu-se-lang-ling, it appears in various forms including "Gurzhe," and is often spoken of as 'O-de-gung-rgyal. A less emphasized figure is Tshangs-pa or Tshangs-pa Dkar-po as a natively Tibetan figure (and not as a translation of Brahma!?). More on this in his 2020 book, vol. 1, pp. 80-93.

Toni Huber, “From Death to New Life: An 11th-12th Century Cycle of Existence from Southernmost Tibet: Analysis of Rnel dri 'dul ba, Ste'u & Sha slungs Rites, with Notes on Manuscript Provenance,” contained in: G. Hazod & W. Shen, eds., Tibetan Genealogies: Studies in Memoriam of Guge Tsering Gyalpo (1961-2015), China Tibetology Publishing (Beijing 2018), pp. 251-350.

Toni Huber, Source of Life: Revitalisation Rites and Bon Shamans in Bhutan and the Eastern Himalayas, Austrian Academy of Sciences Press (Vienna 2020), in 2 volumes. While centered on extensive research into local traditions still current in the eastern half of Bhutan and the adjacent Mon-yul Corridor, issues of broad-ranging areal significance are drawn from them. Highly recommended.

Toni Huber, “The Iconography of gShen Priests in the Ethnographic Context of the Extended Eastern Himalayas, and Reflections on the Development of Bon Religion,” contained in: Franz-Karl Ehrhard & Petra Maurer, eds., Nepalica-Tibetica: Festgabe for Christoph Cüppers, International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies (Andiast 2013), vol. 1, pp. 263-294. See especially pp. 266-267 for the ‘Great Wise Bat’ (Sgam-chen Pha-wang), a useful summary on the subject that also takes up an entire chapter in Toni’s monograph Source of Life.

Siegbert Hummel, “The White Old Man,” tr. by G. Vogliotti, The Tibet Journal, vol. 22, no. 4 (Winter 1997), pp. 59-70. Originally published in German in Sinologica, vol. 6 (1961), pp. 193-206. This discusses the age of his cult in Tibet as well as the exchange of identities between him and the Hoshang.

Caroline

Humphrey, “A Note on the Kalmyk Tsagan Aav, the ‘White Grandfather’: Ritual and Iconography,” might be found posted at

Kalmyk Heritage website.

Tenzin Jamtsho, “The Old Man ‘Mitshering’ at Nyima Lung Monastery,” Journal of Bhutanese Studies, vol. 28 (Summer 2013), pp. 90-99.

This is mainly about the dance figure known to some Bhutanese as the Long-Life Man (Mi Tshe-ring) and to others as Rgyal-po Hwa-shang, suggesting he was both a king and a Chinese monk. In my experience he is always identified as being in some way Chinese, although within the context of the monastic dances he always pays his respects to Guru Rinpoche.

Luther G. Jerstad, Mani-Rimdu: Sherpa Dance-Drama, University of Washington Press (Seattle 1969), pp. 129-135:

Here we have a significant description of the Long-Life Man 0r “Mi-tshe-ring,” with photos of the same in the illustrations between pages 128 and 129. The figures of the Long-Life Man and the Hoshang are combined together, something that happens with some frequency elsewhere, but here in the land of the Sherpas in Nepal, the comic figure takes precedence. He makes valiant attempts to perform simple acts of worship and offering, but fails hilariously each time. Interestingly enough, it is suggested that he was imported by the 13th Dalai Lama from Peking, with not the least mention of Mongolia.

Richard J. Kohn, Lord of the Dance: The Mani Rimdu Festival in Tibet and Nepal, State University of New York Press (Albany 2001), in particular “Dance Five: The Long-Life Man,” at pp. 199-204.

Among the Sherpas of Solu-Kumbu of Nepal, the Long Life Man performance is made up of lay religious practices badly performed by him and his acolytes including offerings of ritual scarves or khatags, prostrations, and, most significantly for our currency iconography.the water torma offering (chu-gtor).

Stephen Little with Shawn Eichman, Taoism and the Arts of China, The Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago 2000). At pp. 268-271 are some marvelous painted scrolls of the Shouxing and at pp. 276-277 a very nice one of Xiwangmu; her assistant holds up a bowl of peaches with the leaves attached, a thing we see sitting on the ground in our Tibetan banknote.

S. Mahdihassan, “The Patron-Gods of Health and of Longevity: Chinese, Greek and Indian,” Bulletin of the Indian Institute for the History of Medicine, vol. 19, no. 1 (January 1989), pp. 111-127. The pharmacology/alchemy of revitalization and longevity hasn’t been my main theme, but I do think this article can instigate important comparative reflections.

Jim R.

McClanahan, “

Journey to the West and Islamic Lore,” a webpage posted back in 2017, but updated earlier this year. Especially pertinent for the parts about the speaking peaches and the Waqwaq tree. Thanks to S.V.V. for suggesting the link.

Rene de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, Tibetan Religious Dances: Tibetan Text and Annotated Translation of the 'Chams Yig, Paljor Publications (New Delhi 1997), pp. 82-84.

As a figure in monastic masked dances, the Hashang is sometimes highly honored and in other cases ridiculed, depending on the audience and what they perceive him to be. It may be that his role in these dances in Tibetan regions is not very old, but introduced by the 13th Dalai Lama after his visit to Mongolia. At p. 83:

“Originally cagan öbö seems to have been a divinity of the pre-Buddhist Mongolian folk religion. He was apparently a clan deity and moreover a benevolent earth spirit protecting the household, the herds, and the pastures and granting rich harvests.”

Jeremy Roberts, Chinese Mythology A to Z [Second Edition], Chelsea House Publishers (New York 2010), p. 114:

“Shouxing (Shou Hsing, Shou-hsing Lao T’ou-tzu) The Chinese god of longevity, connected with a star located in the constellation of Argo. The star is known to many in the West as Canopus, the second-brightest star in the sky.”

Edward H. Schafer, “Empyreal Powers and Chthonian Edens: Two Notes on T’ang Taoist Literature,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 106, no. 4 (October 1986), pp. 667-677. On the Peach Blossom Grotto and so on.

Karma Lekshe Tsomo, “Prayers of Resistance,” Nova Religio, vol. 20, no. 1 (August 2016), pp. 86-98. At p. 92:

“On the second and sixteenth days of the lunar calendar, they go to the field to pray to the White Old Man, a practice of nature worship that predates Buddhism in Central Asian cultures. In this ritual, the women worship the master of nature and make prayers for peace, rain, and abundant crops, and to stave off natural disasters. They make a fire using butter and sheep fat, and present their requests for the welfare of both people and animals.”

Franciscus Verellen, “The Beyond Within: Grotto-Heavens (Dongtian) in Taoist Ritual and Cosmology,” Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, vol. 8 (1995), pp. 265-290.

+ + +

Some Tibetan-language Manuscripts on the White Old Man

Rgan-po Dkar-po Bsangs, ‘Incense Offerings for the White Old Man.’ A 3-folio text, author given as Blo-bzang-bstan-'dzin ming-can. TBRC no. W1NLM61.

Rgan-po Dkar-po-la Mchod-gtor Bsangs G.yang. An 11-folio ms. It seems to bear the title Rgan-po Dkar-po Mdo [see the final line of fol. 11 verso], and it is immediately followed by interesting text we list next. TBRC no. W1NLM2000.

Sa [dang] Chu'i 'Dul-bar Gnon-par Nus Mdo, ‘Sūtra of Power to Subjugate, to Tame, Earth and Water.’ It supplies titles in Chinese and Mongolian as well as Tibetan, and on its 2nd folio it supplies an iconography of the White Old Man. It has all the marks of being a scriptural sūtra, although it is surely not of Indian origins, but locally produced, and for that reason of extraordinary interest. TBRC no. W1NLM2000. I found another version of it with a variant title in TBRC no. W1NLM1842: Sa dang Chu’i Bdal-bar Gnon-par Nus-pa’i Mdo, which I am tempted to translate, very tentatively, as Sūtra on the Power to Prevent Earth and Water from Exceeding their Bounds (there is a lot of variance in the Mongolian language titles and in the ways they have been Englished in the literature).

Rgan-pa [D]kar-po [G]sol-mchod [note the subscribed Dkris, perhaps abbreviation for Bkra-shis]. A 7-folio ms. The colophon says it was written by Tho-go-rtse Tho-tho [clarified in a note as meaning Tho-go-co Khu-thug-tho] at the urging of the layperson (U-pa-shi) Sangs-rgyas-shes-rab. TBRC no. W1NLM1590.

Rgan-po Dkar-po’i Gsol-mchod. The folios are unnumbered, but you can see near the end that its composition is attributed to Padma-’byung-gnas, or Padmasambhava. Contained in TBRC no. W1NLM3102.

Rgan-po Dkar-po’i Gsol-mchod Byas-tshul [=Bya-tshul]. A 9-folio ms. Its colophon simply attributes it to Padma-’byung-gnas, or Padmasambhava. Contained in TBRC no. W1NLM2308.

To this list we ought to add

Srid-pa’i Pha-wang Lha-’bod Lha-’bod Lha Mi Bar-gyi Phrin Gyer, “A Divine Invocation for the Bat of Existence (Life/Evolution): A Chant Message between the Divine and Human,” contained in the scanned volume with the cover title Bsang-brngan Yid-bzhin-nor-bu sogs, pp. 159-174. TBRC no. W4CZ332272. I do find a Pha-wang Lha-’bod, “A Divine Invocation for the Bat,” text listed in a Bon scriptural canon catalog, actually twice, once accompanied by a text called Pha-wang-gi Zhu-ba, “The Questions of the Bat.” Inspired by Toni Huber’s monumental book, I thought I would write up a tiny web-log about these texts, but now I’m thinking someone just like you might be interested in working on them.

§ § §

I’ve merely touched on the subject here, so I recommend a look back at “

Star Water,” an earlier Tibeto-logic blog posted on September 15, 2017, where the Sage Agastya and connections to the Canopus star may become brighter than they are at the moment. Canopus is even entangled with Tibetan swimming festivals, as you’ll see. For more in-depth on the Agastya connection, see Baumann’s 2019 & 2020; Roberts’ 2010.

This blog and the one that came before it represents a blog-ified version of a paper with powerpoint given recently at a small conference entitled “Tibet & the Oirats — Oirat Cultural Legacy and the Earliest History of Tibetan and Mongolian Studies,” held on 14–15 November 2022.

One last thing

Did Tibetans of early times know anything at all about a Peach Blossom Grotto that was supposed to lie at the northernmost edge of their plateau according to Chinese literature? I had my strong doubts, but no definite idea how to answer this question, so I did some creative searching in BDRC’s database. Unfortunately, all I could come up with is

a 2006 publication from the PRC that gives to it a Tibetan name: “Thar-ldan Kham-bu ’Byung Tshal.”* I suppose what is interesting about this source is that it makes a direct comparison with Sems-kyi Nyi-zla (‘Mental Sun-Moon’?). I know that may not ring a bell, but that’s the fake back-translation (or rather phonetic transcription!?) into Tibetan of Shangri-la (as it is pronounced in modern Chinese) that was then used to justify choosing where Shangri-la

as tourist destination would from then on be found. For that exceedingly weird story, see that 2016 Tibeto-logic blog entitled “

Signs of Shangri-la.” Are we even surprised that Wikipedia-wallahs were totally suckered into the rabbit hole? They may never find their way out, and meanwhile human history may never recover from the altered time line unless... Look

here.

(*I thought to unpack this translation: Clearly Kham-bu is the Tibetan word for “peach,” and 'Byung indicates “origin,” so “peach origin.” But Tshal means “Grove.” Did the translator choose a Tibetan word meaning “grove” for the Chinese term we translate into English as “grotto”? A grove is not a grotto... Oh, and Thar-ldan means “Having Freedom,” right?)