Let’s not make this about me, but I’d like to lead into the subject lightly by telling a story that does involve myself. I believe it may help explain my enthusiasm for the subject.

When it came time to make a formal proposal for my doctoral dissertation back in the mid-80’s, I couldn’t make up my mind whether to be a modernist or a medievalist. One idea I had was to study Kongtrul and the Nonpartisan or Non-sectarian Rimé movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After a lot of thought, I decided to leave the modern world behind, and concentrate on a Bonpo teacher by the name of Shenchen Luga, who revealed Treasure texts in 1017 CE. It was a few years later on that I decided I ought to take a step back and look at the world surrounding him, to learn more about the period of Tibetan history prior to the advent of the Mongols on the world’s stage. Although I have often stepped outside the boundaries, the fact is I still largely occupy myself with this time in Tibetan history.

I believe it was in 1987, passing through Paris on our way to Kathmandu, that we stopped by Rue d’President Wilson to visit two illustrious professors, Samten Karmay and Anne-Marie Blondeau. Madame Blondeau gave me a small lecture about medieval manuscripts being like organisms that grow and change over time, and how those of us who study 11th-12th century Tibet need our own equivalent of the Dunhuang cave cache in order to better know those times without seeing through later filters.

It was only in recent months that it occurred to me that we have not only one, but four and possibly even more caches that may more or less perfectly fill the need Madame Blondeau expressed so nicely.

|

|

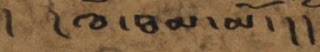

Let me show you one of the several stages in my thinking about the subject of the four caches. The Matho fragments became available only October of last year, but the Gatang texts have been known since 2006. I knew of the Gatang cache thanks to their facsimile publication along with several important studies. If you read Tibetan look at line 4 beneath the arrow and you’ll see that the author Pematashi mentions a cache of 11th- to 12th-century texts found in 2011 in Tholing. He notes that, in both the Gathang and the Tholing caches, quite a few of the texts are in the form of side-sewn booklets he calls “Ltebs-zur-ma.” As this was written well before the Matho fragments became known, it is all the more remarkable that the same is true of them. A large percentage of the Matho are in fact side-sewn booklets.

But there was one more small step in the slow progress of my enlightenment when I realized that a book with facsimiles that I already had (thanks to a scan given to me by one of the editors), was a set of Khyunglung manuscripts. I had written a blog about one of the texts, but hadn’t paid the others much attention. Although as I guess I’ll discuss soon, the Khyunglung manuscripts may have been closed later in the 13th century — as much as a century after the others — it occurred to me that it could make a great deal of sense to think of all four caches at once. So, even though I will concentrate in the end primarily on the Matho, we will briefly but slowly work our way through the others one at a time.

You could say that I want to promote three basic ideas or theses, and if one or another is only partially proven we’ll consider the effort repaid.

1. The 21st century availability of these manuscript caches is a significant transformative event. It’s comparable to the Dunhuang caches, only with a cutoff date two centuries later than the Dunhuang.

2. We don’t understand the post-imperial but pre-Mongol era of Tibetan religious history as well as we think we do. Views are going to change.

3. More specifically the subject of my next blog: The religious movements, schools of sects of that time emerged in an interactive and interconnected way, much more than assumed.

We may not always be aware of it, but the field of Tibetan Studies in our still-new century is facing a number of dangers and transformations. Among them: Even while prospects open ahead of us we face the danger of lost opportunities. During my times I have witnessed quite a few attempts, some successful, in pushing us in different directions. But regardless of the direction the crowd decides to take it always involves some significant questions and approaches being abandoned, approaches that could have yielded interesting results on their own.

I would be happy if only I could finally succeed in nearly convincing you that these 21st century discoveries will be recognized as a significantly transformative event for Tibetan studies, almost if not quite on the level of the Dunhuang cave cache with their closure date two centuries later. Slowly but surely these texts are going to persuade us that we do not know the post-imperial pre-Mongol period as well as we think we do. And along those lines but more narrowly, I’d like to supply enough evidence so you will agree with me that the religious movements, schools or sects coming into life, or coming back into life, in those times when they had their new beginnings were a lot more interactive and connected to each other than we have been thinking.

To the best of my present knowledge three of the caches were closed within their chortens in around 1200 CE, while the fourth was deposited late in the 12th century. Still, nearly all the texts date before 1200. Some of them may have been scribed as early as two centuries before that time, in some few cases quite possibly earlier still.

I will go on and introduce them one at a time, in order, starting from the east and proceeding west, following the course of the sun across the sky. There’s

- The Gtam-shul Dga'-thang chorten cache published in 2007,

- The Khyunglung/Sutlej chorten texts found in 2008,

- The Tholing find of 2011, and

- The Matho chorten fragments found in 2014 now posted at BDRC.

So, as you can see by moving in space from east to west, they are also chronologically arranged according to find dates. We might consider the possibility of adding Tabo manuscripts as a fifth item, although these were preserved in the temple, and not in a chorten, and the dating of each individual manuscript is more of a problem as the collection remained opened for one whole millennium. At the very least some Tabo texts can be made a part of our arguments. I’m entirely open to other ideas about what might be added.*

(*A fantastic book that only now reached publication constrains us to consider two more caches of early texts, those in ’On Ke-ru in south-central and Phu-ri in Gnya’-lam southwestern Tibet. See Matthew T. Kapstein, ed., Tibetan Manuscripts and Early Printed Books, Cornell University Press [Ithaca 2024], vol. 1, p. 22, note 6, noting also in the same volume p. 122, notes 22 and 30.)

There are lots of codicological and paleographical aspects we might touch on here and there, but there are good scholars among you prepared to do a lot better work on this than I can. So I would encourage them to go to work. My aims today are different, not being much concerned with the physical volume and so-called materiality. I want to know what these fragments can tell us about the world they inhabited, and particularly the spiritual worlds they inhabited, the religio-spiritual traditions both exoteric and esoteric.

But first, I need to consider objections that may have already occurred to you involving contemporary issues of cultural property and unprovenanced artifacts. We should set these issues aside for the time being, because they could really take over and leave time for nothing else. But, well, we have to say a little at least.

Put simply, chorten desecration does happen and it’s a real problem. However, in the case of the Gatang, the texts were found during the course of very necessary repairs.

The Matho texts were found during the de-construction of the chorten or chortens, but this was done under the orders of the locally most highly regarded religious leader, a Rinpoche, specifically Luding Khan Rinpoche.

The other two caches are not so clear to me, but even if the chortens may have been damaged by looters (this is never clarified), the texts were found onsite after the fact by people with motives of preserving and protecting the monuments.

None of the four caches I will discuss are supplied to us by the looters (the looters thought they might find items of more value than bits of paper and bark). I think that fairly resolves one ethical qualm even if not entirely, and leave the rest for future discussion.

This map is supplied to give general idea of the site location of Gatang, just to the north of the eastern part of the northern border that divides Bhutan from Tibet.

Here you see the premier publication that reproduces all four texts found in Gatang Chorten.

Looking at Samten Karmay’s essay (I’ll give the reference in a moment), he tells us how books were found inside a large and quite old chorten during its restoration in 2007. The person in charge of the restoration and the one who actually found the manuscripts was Langru Norbu Tsering (Glang-ru Nor-bu-tshe-ring). He co-authored the book you see here with the wellknown scholar Patsab Pasang Wangdü (Pa-tshab Pa-sangs-dbang-’dus).

If this chorten was indeed built as a kind of tomb memorial for the Nyingma Tertön Nyangral Nyima Özer, its closing ought to date from somewhere around 1200.*

(*His death date is sometimes placed before, and sometimes after, that year. For more on him see this book: Daniel A. Hirschberg, Remembering the Lotus-Born: Padmasambhava in the History of Tibet’s Golden Age, Wisdom [Somerville 2016].)

This is just to provide a visual example of a page from one of the Gatang texts. Look where the arrow is pointing to see one of the real oddities of these early texts. They could actually split syllables between lines, something unimaginable in later texts. When I first saw it I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Now I’d like to place before your eyes some of the most significant writings about the Gatang texts so you can study them for yourself if you find the interest. John Bellezza has studied all the texts with the exception of the medical text.

|

|

There is one monographic study (see just above), along with a shorter article, by a woman scholar Chagmo Tso (Lcags-mo-mtsho). She says the cache, found in 2006 during reconstruction, included not only the four texts, but also divine images and thangka paintings. She thinks the texts date between mid-eighth to end of ninth centuries. She says (p. 254, point no. 3) the Bon texts were found within the Vessel (Bum-pa), demonstrating that the Bum-pa-che was originally a Bon monument. The words “Rgya-gar Chos-kyi Skad” were added at the beginning marking them as texts originally in an Indian Buddhist language, in order to protect these in fact Bon texts from destruction in the time of Trisongdetsen. Orthography and commonalities of place names (with names of regional lords) convince her the Gathang cache is contemporary to and just as good as Dunhuang.

I can’t follow some of these reasonings, which could be my problem. If you ask me she is a little too confident about the documents themselves dating back to imperial times, as in every way equivalent to Dunhuang documents. But she does add much to the discussion, and there is a lot to learn from this book, especially on matters of codicology. It deserves a closer reading than I’ve been able to give it.

|

|

Here you see a few more publications on the Gatang.

To continue with information from Samten Karmay’s essay... This bundle of manuscripts contains three ritual texts and one medical. Evidently the chorten is associated with the death of Nyangral Nyima Özer and dates from that time. That means the texts were likely closed inside at the very beginning of the 13th century. Karmay believes the mss. themselves are pre-11th century. Toni Huber says 11th-12th century. My opinion? I think late 10th-11th c. is a safe enough guess.*

(*They were scribed for ritual use, and enclosed in the chorten only after the practices they advocated were no longer in use locally; that’s just my opinion, likely they were at least a century old already when they were placed inside.)

Toni Huber’s article is on the Rnel-dri text (the same one illustrated in slide 5), and the same text features in his book Source of Life (2020), vol. 2, pp. 40-49. The rite is primarily concerned with “the post-mortem status of deceased foetuses or miscarried infants and in some cases their mothers, and how this impacts upon the living.”

So, to reiterate: The book by Chagmo Tso tells us and shows in a photograph precisely where inside the chorten these Bon texts were found. This single bundle of manuscripts contained three ritual texts and one medical. Evidently the chorten is associated with the death of Nyangrel Nyima Özer and this gives us a date for the sealing of the texts within it. That means all the texts would have to be twelfth century or earlier, and this is generally confirmed by their actual content.

|

|

Now for Khyunglung in the upper Sutlej River valley. At this moment I will not dwell on the interesting questions that have grown up around this place called Khyung-Bird Valley and its Silver Castle, just to say that it has a pivotal importance in numerous arguments being made in our day about the importance of Bon and Zhangzhung in Tibetan history. And archeologists have played a significant part in these discussions. But this is too unconnected to the matters of concern at the moment to go through all of that here.

(*It is true that the first reproduction in the facsimile edition is surely Bon. It is the only self-evidently Bon text in any of the four caches, with its mentions of Lord Shenrab. The three Gatang texts are not so self-evidently Bon, and could be described as ‘village rites.’)

Here you see the 2021 publication with facsimiles of the Khyunglung texts.

Here is the link to a blog that I wrote over four years ago: “Stone Inscription from the 8th-Century Rule of Trisongdetsen Suddenly Shows Up.” The title is slightly off according to my present understanding, as it leads you to expect an inscription carved in stone, while what we have is at best a paper copy of a stone inscription. The earliest reports about it were very confused and confusing and the main studies have yet to appear in print. It is still supposed by many to be a paper copy of a long stone (rdo-ring) inscription, and more specifically the long stone that once stood at the imperial period temple Tradumtsé (Pra-dum-tse). I won’t discuss this complex matter, although it is significant that an official edict type of document from imperial times was preserved with the other mostly Buddhist texts (the first item in the facsimile edition is in fact a Bon text). One modern writer has judged the edict to be a forgery, even if a forgery made during imperial times. All very interesting but not on topic. I will send you to the blog if you want to find out more. It is appended with numerous updates and possible leads for further study.

|

|

Apart from the imperial edict, another most interesting thing I noticed in the Khyunglung cache is germane to our subject, so I’d like to delve into it a little with the idea to do more on it in the future if I can. I had at first thought it might be a Zhijé text containing words of Padampa. From what I can see, the ordering of elements is not the same as the translated version, which could have relevance for the history of the text. Even before knowing about the Khyunglung fragments, I had noticed text parallels and similar metaphoric usages in the Zhijé Collection, indicating common sources or cross-fertilization. Perhaps the metaphor of the turtle in the bronze basin would provide a sufficient example for the present. As I was planning a blog on this very subject, I’ll put my evidence in an appendix down below for the entertainment of the diehard Tibetologists among you.

|

|

This is just to show an icon of Zurchungpa and his dates. He was significant for the Mahayoga lineages of the Nyingma school, and a celebrity in his time and place.

Here is a sample page.

Note: That word kha-rje on line 5 might be calqued with honor or merit. It is hardly used after the Mongol advent. It’s spelled variously (in one spelling it might seem to mean something like “king in the castle”). A cultural concept that is difficult to translate exactly, although I suggest honor as one good option. It seems to carry with it the senses of strength and integrity, but also having what is one's due, social standing, merit etc. Notice, too, on line 6: Dam pa’i zhal nas. This is what made me think it might be a Padampa text.

Now for the Toling cache. I won’t say much about it because, to the best of my knowledge, with one unique exception its texts have not been made public.

We already noticed in Pema Tashi’s one-volume book on codicology (Bod-yig Gna’-dpe'i Rnam-bshad [2013], p. 15), he says booklet format Tibetan texts were found in a chorten near the Golden Temple of Tholing, dating to 11th-12th centuries. Other sources inform us the finding happened in the year 2011.

Unfortunately, the content of the Tholing Chorten cache is not sufficiently known to allow it to figure into our research aims of the moment, as I can say nothing about which Tibetan schools are represented in it.

I know of one and only one publication of the Tholing Chorten texts. In 2017, David Pritzker completed his D.Phil. at Oxford with a dissertation on a very old top-bound booklet from Tholing containing a mid-to-late 12th-century Tibetan history that was otherwise unknown. The same author has published several brief essays on this same subject, and I also noticed this rather recent publication listed somewhere in case you would like to try and locate it where I couldn’t:

Khyungdak Dhartsa’s (’Dar-tsha Khyung-bdag) research article “Mtho-lding Dgon-par Bzhugs-pa’i Rgyal-rabs Zla-rigs-ma Ngos-sbyor Mdor-bsdus,” Tibetology of China, issue no. 4 for the year 2013.

This illustrates a sample page from the history text booklet, top-bound rather than side-bound. To see the entire text, go to BUDA and type this number into its search box: W4CN12077.

Now at long last we’ve arrived at the Matho cache where we will remain for what remains of this blog. It would be a journey of nearly 900 miles if you could travel directly between Number 1, Tamshul near Bhutan, and Number 4, Matho in Ladakh. Rest assured no such direct route exists. Your trip will be much, much longer.

The old Matho chortens, including the King’s Chorten said to be source of the texts (or at least most of them), were disassembled following the wishes of the widely respected religious leader Luding Khan Rinpoche in the spring of 2014.

Why were the texts originally placed there? Helmut Tauscher believes it likely they were brought from nearby Nyar-ma Monastery. This makes sense and there is nothing to argue against it.

It was a library regarded as sacred, but it had over the centuries suffered from accident, neglect or partial destruction. There are indications of presumably accidental fire, but other natural or human causes could explain it. Water and mold damage are sometimes evident. It is difficult to know how much of the deterioration of the text occurred before, and how much after, their enclosure in the chorten[s].

An often asked question, Is it like a geniza? In Judaism, a geniza is created because the very letters of the script need to be disposed of in a respectful way. But in Tibet fragments of texts are placed inside chortens so that the chorten can benefit from the added holiness. The distinction is not so subtle, and might be taken as a difference in motive. The genizah texts are respectfully disposed of when they are no longer of practical use, while the Tibetan texts are, in addition, made part of the shrine where they remain as a contributing cause for its holiness. Although I won’t pursue this here, I believe in both cases it may be understood that, in a sense, a funeral is taking place.

Just about everything you need to study Matho fragments is freely available on the worldwide web. Just go the links seen above. The one with the star is most highly recommended.

I’ve put together in one list some interesting writings about Matho Monastery in general, although for our purposes the article by Helmut Tauscher with the star next to it is the only one that really requires attention. You see that others are mainly concerned with local protective spirits and possession rituals.

Here is an interesting photo I found in an Instagram post online. The fragments we find reproduced for us in BDRC are not that small, and it seems that the tiniest paper or birchbark fragments have not been included. In BDRC there are only larger pieces.

A Google search led me to this Facebook page for the Matho Museum, where I saw the remarkable statement you see in slide 22 with an arrow I’ve added to call attention to it. Just imagine storing old manuscripts in a bag. Think how that may in itself be productive of small fragments. I’ve stopped thinking.

•To be continued•

Just click on this: Continued here.

Appendix: The Turtle in the Bronze Basin

Do you ever even imagine that effort itself could in some circumstances prove to be an insurmountable impediment to progress? Counterintuitive insight at its best! I am now convinced the metaphor of the turtle in the bronze basin will be subject of a forthcoming blog. At least I will try and try again. Wait for the future, as I suppose we have all been doing without complete success.