|

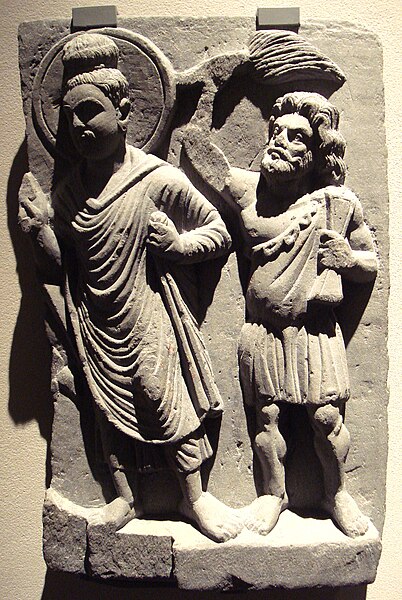

| Sakya Jebtsun Dragpa Gyeltsen, holding Vajra and Bell

© Trustees of the British Museum

|

Today’s post is a continuation of this one.

There is a very interesting twelfth-century Tibetan work by Dragpa Gyeltsen (Grags-pa-rgyal-mtshan) that we will summarize here, emphasizing his explanations of the symbolism of the parts of the Vajra. He lists four types of Vajras, but of these he only discusses the Symbolizing Vajra, the physical Vajra that can be held in the hand. He then names four types of Symbolizing Vajras:

[a] The nine-pointed Vajra called the Commitment Vajra.[b] The five-pointed Vajra called the Full Knowledge Vajra.[c] The three-pointed Vajra which is the Vajra used for exorcising inimical forces.[d] The Vajra with open ‘horns’ (prongs) called the Wrathful Vajra.[1]

Dragpa Gyeltsen suggests that the proportions should be (as they seem to be in actual practice) in three equal parts — the two pronged ends and the central part being of equal length. He also recommends, supporting himself with a quote from a tantra, that there should be a bulging part (a ‘globe’) at the center where the Vajra is held (generally between the thumb and fingers of the right hand). One scriptural source, the Sampuṭa Tantra, in fact calls this, “The egg of the three times, at the center, into which the Full Knowledge deity is to dissolve.”[2]

A verse, of Indian origins, but cited by a recent Tibetan author, says that it has a lion’s claws, an elephant’s trunk, a makara’s (crocodile’s?) tusks, a monkey’s eyes, a wild boar’s ears and a fish’s body.[5] It lurks beneath the water among the lotus stems, and a lotus stem (or rhizome) is sometimes depicted coming out of its mouth. It is the ruler of the depths of the ocean, that vast and dangerous realm that seems so chaotic to us, or at least subject to totally different norms, an almost entirely ‘other’ world. It may nevertheless be a source of great riches, so much so that one common epithet of the ocean is ‘jewel source.’ The Makara, as a composite creature, embodies all the danger and strangeness, as well as the potentialities, of that separate world beneath the water’s surface.[6] As a crocodile-like monster capable of swallowing whole creatures, including people lost at sea, it represents not only all-consuming passions, but also radical transformation (by way of a process of ‘digestion’), a symbolism that is evident also in the Face of Glory, but becomes especially clear in the case of the Purpa symbolism, a subject we may come to later on. The Makara is responsible for stopping up the flow of waters, but also for releasing them. Its use as a symbol of fertility has often been noted, and it is probably of some significance that Kāma, the divinity of sensual desires, is supposed to hold a Makara banner.[7] Dragpa Gyeltsen says, “Those ‘horns’ [i.e. the prongs, which the Tibetan texts also call ‘points’] emerging out of the mouth of the Makaras are a symbol of being drawn out of the suffering at the root of life. The lunar circle that forms the seat of those ‘horns’ is a symbol of relieving the heat of the vicious circle of saṃsāra of its affliction [with its cooling lunar rays].”

|

| Lalitpur, Nepal 2011 |

|

| Lalitpur, Nepal 2011 |

|

| Alchi (Ladakh) mural. Notice the black ‘spidery’ look of these Vajras, a characteristic of western Tibetan art a thousand years ago |

A later writer of the Tibetan Gelugpa school by the name of A-kyā Rinpoche classifies Vajras (following the Highest Yoga Tantras) into two types: [1] the Meaning Vajra which is the thing symbolized and [2] the Sign Vajra which acts as a symbol. The Meaning Vajra is identified as the Full Knowledge identical to the mind of the Buddha. It is also called the Secret Vajra. The Sign Vajra is symbolic of Full Knowledge. He further distinguishes Sign Vajras on the basis of the number of prongs, on whether or not the outer prongs touch the central prongs, and on whether the prongs are blunt or sharp at the end. Ones with sharp prongs that do not touch the central prongs are wrathful Vajras, while the ones with blunt prongs that do touch the central prongs belong to the peaceful type. He cites one tantra to the effect that Vajras may have as many as one thousand prongs, but he notices only five main types based on the number of prongs, the one-, three-, five-, nine-pronged, and finally the Everything Vajra — sometimes called the Crossed Vajra since it has four sets of prongs arrayed in the four compass directions — which might be 12- or 20-pronged depending on whether there are three or five prongs in each of the four sets.[10]

One Indian text by Advayavajra describes the Vajra in terms similar to those of the Tibetan-authored texts, identifying the bulge at the nave as a symbol of Dharma Proper (chos-nyid, essentially equivalent to the Dharma Realm, chos-dbyings, of Dragpa Gyeltsen), and the five prongs he identifies as symbols of the five Buddha families. This text at least can demonstrate for us that the most important elements of Dragpa Gyeltsen’s symbolic analysis already existed in India.[11]

To reiterate, the Vajra — in both its name and symbolic, mythological associations — originated in India where in very ancient times it was the weapon of Indra. Still, it is most likely that the form of the Vajra known to Tibetans (and other Buddhist countries) came to India, perhaps somewhere in the second to fifth centuries, in a form known to the Greeks as the Keraunos, weapon of Zeus. In the earlier Buddhist art of Gandhāra the Vajra was portrayed, but in a quite different form. The Vajra as a whole may be described as a symbol of indestructibility, stability and firmness. By extension it became for Buddhists a symbol of particular things characterized as adamantine: the resolution to obtain Enlightenment (usually called the ‘Thought of Enlightenment,’ Bodhicitta), Full Knowledge, and the Buddha’s body, speech and especially His mind. Those particular meanings known and employed in the Buddhist tantras all seem to have found direct inspiration in Mahāyāna sūtras.

Although we have noticed no specific textual source for the idea, it is entirely possible to view the parts of the Vajra as symbolic of the Three Bodies of the Buddha. The two ends appear to be growing outward from the central undifferentiated globe, stated to be a symbol of the the nature of things, that is equivalent to Dharma Body. The circlets of pearls on either side of it would then be a symbol of the Dharma Body ‘with ornamentation’ (in other words, the minimal degree of manifestation and incipient multiplicity), perhaps symbolic of the Perfect Assets Body that displays, to highest level Bodhisattvas only, the richness of the Dharma Body. Then, proceeding still further outward, there are two Lotuses, symbols of the unfolding of Enlightenment, likewise symbols of pure and miraculous conception and birth, which provide the support for the five Buddha Families of the five prongs that may become visible, in the form of Manifestation Bodies, to ordinary human beings. This picture is at least in keeping with the role of the Vajra, in the form of the four-ended Everything Vajra, in Buddhist accounts of cosmogony, underlined by the fact that the Everything Vajra is visible as the ‘ground’ for the manifestation of the Maṇḍala.[12]

Although we have noticed no specific textual source for the idea, it is entirely possible to view the parts of the Vajra as symbolic of the Three Bodies of the Buddha. The two ends appear to be growing outward from the central undifferentiated globe, stated to be a symbol of the the nature of things, that is equivalent to Dharma Body. The circlets of pearls on either side of it would then be a symbol of the Dharma Body ‘with ornamentation’ (in other words, the minimal degree of manifestation and incipient multiplicity), perhaps symbolic of the Perfect Assets Body that displays, to highest level Bodhisattvas only, the richness of the Dharma Body. Then, proceeding still further outward, there are two Lotuses, symbols of the unfolding of Enlightenment, likewise symbols of pure and miraculous conception and birth, which provide the support for the five Buddha Families of the five prongs that may become visible, in the form of Manifestation Bodies, to ordinary human beings. This picture is at least in keeping with the role of the Vajra, in the form of the four-ended Everything Vajra, in Buddhist accounts of cosmogony, underlined by the fact that the Everything Vajra is visible as the ‘ground’ for the manifestation of the Maṇḍala.[12]

The use of the Vajra for protection, especially associated with the early protective role of Vajra Wielder, is quite pronounced in ritual contexts, without in the least excluding or replacing any of the usages we have discussed so far. The contemplative visualization of a Vajra Wall is essential to the inner work of the tantric practitioner, since this Wall (in effect an encompassing three-dimensional sphere), entirely made up of Vajras, protects the mind (as does the mantra repetition known as Vajra Recitation) from distracting or delusive invasions that might otherwise disturb the meditative practice.[13] Other ritual and visualizational uses of Vajras are too numerous to mention. They appear at every turn. During most monastic rituals, the Vajra and Bell are held in the right and left hands while making various ritual gestures, symbolic of the interplay and union of method and insight, the two parents who give birth to Buddhas, as well as the yogic process of dissolving the energies of the right and left psychic channels into the central channel. Some ritual sequences are directly devoted to the Vajra and Bell, such as the ‘Vajra and Bell Blessing’ that often forms a part of the preliminaries of a number of rituals such as the sādhana and the Fire Ritual (Homa). Another such ritual is Vajra Master Initiation, in which initiates are presented with a Vajra and a Bell as signs of their capability to preside at such tantric rituals as Homa, consecrations and empowerments.

Still other specific usages may be seen in consecrations and in the blessing of sacramental medicines. In these last-mentioned contexts, a relatively small, approximately hand-width sized Vajra is kept tied to one end of a Dhāraṇī Thread that acts as a kind of ritual ‘power line’ to conduct the meditation-generated force from the ritual master to the item/s being consecrated.[14] But not all of the symbolic usages took place on such sublime spiritual and ritual levels. Sitting on my desk as I write are two Tibetan government-issued bank notes of twenty-five and one hundred srang denominations, dating to the last half of the 1940’s. The black seal of the Tibetan government bank (or, after 1937, the seal of the official mint) stamped on the front side of each note is framed by four Vajras, that might also be understood to symbolize the inviolability of the state bank and/or its currency.[15] Well, to wrap up this discussion for the time being, the Vajra and Bell, presented to the tantric practitioner through a ritual initiation, remain for them the most essential implements, and will be kept on the altar of all who are engaged in Buddhist tantra. Next we turn to the Bell. Until then...

_____________________

|

| Detail from an 100 Srang Note of the Tibetan Government. Note the four Vajras surrounding the ’Phags-pa inscription that reads: Srid Zhi Dpal ’Bar, or “Blazing Glory of Both Worldly Life and the Quiescence of Nirvana” (I know, 4 syllables shouldn’t need 18 in the translation) |

_____________________

[1] This four-fold classification of

Vajras evidently comes from the chapter on Vajras and Bells in the Vajra

Skygoer Tantra (Vajraḍākanāma

Mahātantra Rāja),

on which, see Helffer (1985: 55). It is interesting that this classification

doesn’t leave room for a one-pronged Vajra, since this type is known to

Japanese Shingon art, and a number of later Tibetan writers do mention its possibility.

Later on, in our discussion of the Phur-pa, we will see how the Phur-pa might

be conceived as a single-pronged Vajra.

[2] Toh. no. 381. Derge Kanjur, vol.

79 (ga), fol. 144 recto: dbus-su skabs gsum sgo-nga-la

// ye-shes lha ni thim-par bya. The Sanskrit text of the Sampuṭa Tantra exists in the manuscript form,

and a published edition is said to be forthcoming. Three Indian commentaries

are available in Tibetan translation (Skorupski 1996). Obviously, a further

study of these sources, overcoming the inherent difficulties in dealing with

texts of this nature, would reveal important information on Vajras and Bells.

[3] However, we have not noticed that

Tibetan sources actually use a word for ‘tongue,’ and in Indian representations

of the Makara, it is rather the Lotus rhizome that is depicted coming out of

the Makara’s mouth.

[4] See Vogel (1957: 561-564). Note

also the early Buddhist examples of Makara portrayals from Bharhut, Amaravati

and Sarnath in Vogel (1924 and 1930). Smith (1988) observes how various types

and shapes of Makaras occur in different times and places.

[5] Dge-’dun-chos-’phel (1990: I 69).

[6] On the Makara, see especially

Coomaraswamy (1971, pt. 2: 47-56) and Darian (1978: 114-125), where it appears

in iconography as the ‘mount’ or ‘vehicle’ of the Goddess of the Ganges. Many

early Indian examples are given in Viennot (1954, 1958). On a visit to Yamdok

Lake on the south side of the Brahmaputra River in Central Tibet, we asked our

Tibetan driver if anything lived beneath those deep turquoise waters, the

product of millenia of internal drainage (now deplorably slated to be drained

and muddied in order to supply a few years of electricity to the city of

Lhasa). He told us with considerable conviction that nothing lived there except

the Chu-glang. The Chu-glang, or ‘Water Ox’ (perhaps a derivative of the

Jalebha, or ‘Water Elephant’ of Indian lore closely related to the Makara), is

another hybrid aquatic creature that Tibetan folklore sometimes confounds with

the Makara (in Tibetan folklore the Makara, which they call Chu-srin, is the

nearly undisputed leader of the underwater kingdom, whose only significant

danger comes from the conch). It seems to be something like a lion-faced fish

with walrus-like tusks. It doesn’t really resemble descriptions of the Loch

Ness monster, but still the analogy might come to mind. It may be of interest

to notice here that L. Austine Waddell (1854-1938), while accompanying the

Younghusband Expedition invasion of 1903-4 as a ranking officer with an army

consisting primarily of Indian sepoys, credited himself with discovering a new

kind of carp living in Yamdok Lake, that he was no doubt proud to have named

after himself (see Waddell 1905/1988: 304-306, with illustration of the fish

opposite p. 306, as well as p. 489, where the Yamdok carp is given the

scientific name Gymnocypris waddelli).

[7] See especially Stein (1977: 59,

et passim). Stein argues that the ‘prongs,’ which the Tibetan texts usually

call ‘points’ (rtse) or ‘horns’ (rwa), ought to be understood to be ‘tongues’ (in Tibetan lce or ljags) of the Makara, and goes on to

find something ‘phallic’ in these tongues. He doesn’t supply very much Tibetan

evidence for this interpretation (and the unfalsifiability of Freudian

interpretations and their cultural embeddedness are well known problems among anthropological thinkers).

“Makara Banner” (Makara-dhvaja) is also the name of a long-popular Indian

aphrodisiac (Coomaraswamy 1971, pt. 2: 54; Mahdihassan 1991: 88). The use of

the term ‘horns’ in some Tibetan texts might recommend comparison with horns of

protection in other cultures, especially given the protective role of the Vajra

in several of its contexts. The horns on Michelangelo’s famous statue of Moses

go back to some early synagogue prayers which interpret the horns of Moses at

the time of the revelation of the Torah (based on the ambivalence of the Hebrew

word keren,

meaning both ‘[light]beam’ or ‘horn’) as being meant to protect him from the

Angels zealous of their exclusive rights to close proximity to the deity (see

Flusser 1992: xvi, and references given there; with thanks to M. O., Jerusalem,

for suggesting the analogy).

[8] For numerous examples, both drawn

and photographed, of Makara waterspouts from all periods and regions of south

Asian history, see Dhaky (1982). While rich in illustrations, this article is not

very strong on symbolc understanding, but note at least the statement on p.

134, “The choice of the makara as the animal for decorating the drain-front could have

been actuated by the watery association of the animal.”

[9] Mkhas-grub-rje (199x: 230) observes

that the string of pearls that one often sees intervening between the lunar

disks and the lotusses is meaningless, since what should be there, according to

his Indian authorities, is a design representing the railing or outermost wall

of the maṇḍala. This element is often referred to as a sash or girdle (in

Tibetan ske-rags).

[10] A-kyā (n.d.) is largely based

(and this is so stated in A-kyā’s own colophon) on the much more detailed,

early 15th-century work by Mkhas-grub-rje (199x), which has not been directly

cited here. For his explanations of the Vajra and Bell, Mkhas-grub-rje relied

largely on works written by the Bengali Ānandagarbha, an important figure in

the history of the Yoga Tantras. All these Indian works cited by Mkhas-grub-rje

and others ought to be studied in some detail in order to know more about the

Indian background of Tibetan observances.

[11] For an English translation of the

portion of Advayavajra’s (his name itself means ‘Nondual Vajra’) text on

Vajras, see Snellgrove (1987: 133-134). It is also interesting that Advayavajra

cites (without specifying the source) the tantra passage on Vajra which we have

translated above. This Advayavajra was evidently the teacher by that name

active in India in the eleventh century.

[12] On some Maṇḍala representations,

it may be difficult to make out the tips of the prongs of the Everything Vajra,

since the four gateways are flattened outward as a strategy for representing a

three-dimensional object in two-dimensional form (see the following note). The

gateways usually cover all but the tips of the prongs of the Vajra, and

sometimes the outer prongs appear in such a way that they might be mistaken for

elephant tusks.

[13] One may also look at a picture of

almost any Maṇḍala, and find among the outermost circles (generally just inside

the ring of purified elements represented by rainbow colors) a Vajra Wall

marked by vertically oriented Vajras. The Vajra Wall in Maṇḍala representations

(depicted in two dimensions, but intended to represent three dimensions;

although relatively rare, three-dimensional models of Maṇḍalas do exist in some

Tibetan temples, but even then the Vajra Wall is left in two-dimensional form,

since otherwise it would completely envelop the Divine Palace within its

sphere) maintains the inviolability of the enclosed sacred space inhabited by

male and female Buddhas. One tantric work explicitly identifies the garlands

(rosaries) and barriers (walls) of Vajras in the design of the Bell with the

Divine Palace (i.e., the Maṇḍala); see Helffer 1982: 261.

[14] Very often, the Dhāraṇī Thread is

held by all the persons participating in the ritual in question, sometimes even

including laypersons in the audience, and not just the Vajra Master. I have

witnessed this in both Newari and Tibetan ritual practice. For a discussion of

its use in the context of consecration rituals, see Bentor (1996: 111 ff.). On

the Vajra Master Initiation just mentioned, see the latter work (p. 252,

especially).

[15] For illustrations, even if not

very clear ones, see Panish (1968).

° ~ ° ~ °

Literary sources:

A-KYA RINPOCHE

n.d. A-kyā

Blo-bzang-bstan-pa’i-rgyal-mtshan (b. 1708), Sngags-kyi Brtul-zhugs-kyi

Yan-lag ’Ga’-zhig Ji-ltar Bya-ba’i Tshul Bstan-pa Don Gsal Sgron-me [‘Meaning Clarifying Lamp Showing How to Perform

Some Ancillary Tantric Activities’].

Contained in his Collected Works (Gsung-’bum), vol. 7

(key-letter ja), in 24

folios. I used a transcript of the

version in the Chicago Field Museum’s Berthold Laufer collection, no. 131.08.

BENTOR, YAEL

1996 Consecration

of Images and Stūpas in Indo-Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, E.J. Brill (Leiden 1996).

COOMARASWAMY, ANANDA K.

1971 Yakṣas, Part I and Part II, Munshiram Manoharlal (New Delhi

1971).

DARIAN, STEVEN G.

1978 The Ganges in Myth and History, University Press of Hawaii (Honolulu 1978).

DGE-’DUN-CHOS-’PHEL

1990 Dge-’dun-chos-’phel-gyi

Gsung-rtsom [‘Works of Gendun Chomphel’],

Bod-ljongs Bod-yig Dpe-rnying Dpe-skrun-khang (Lhasa 1990), in 3 vols.

DHAKY, M.A.

1982 The Praṇāla in Indian, South-Asian and

South-East Asian Sacred Architecture, contained in: Bettina Bäumer, ed., Rūpa

Pratirūpa: Alice Boner Commemoration Volume,

Biblia Impex (New Delhi 1982), pp. 119-166.

DRAGPA GYELTSEN

See

Grags-pa-rgyal-mtshan.

FLUSSER, DAVID

1992 General

Introduction, contained in: H.

Schreckenberg & K. Schubert, eds., Jewish Historiography and Iconography

in Early and Medieval Christianity, Van

Gorcum (Assen 1992), pp. ix-xviii.

GRAGS-PA-RGYAL-MTSHAN (1147‑1216)

1968 Rdo-rje Dril-bu dang Bgrang-phreng-gi De-kho-na-nyid [‘The True Reality of Vajra, Bell and Rosary’], contained in: Sa-skya-pa’i Bka’-’bum, Toyo Bunko (Tokyo 1968), vol. 3, pp. 271-2-4 through 272-3-6.

1968 Rdo-rje Dril-bu dang Bgrang-phreng-gi De-kho-na-nyid [‘The True Reality of Vajra, Bell and Rosary’], contained in: Sa-skya-pa’i Bka’-’bum, Toyo Bunko (Tokyo 1968), vol. 3, pp. 271-2-4 through 272-3-6.

HELFFER, MIREILLE

1982 Du

texte à la muséographie: données concernant la clochette tibétaine dril-bu, Revue de musicologie, vol. 68, no. 1/2 (1982), pp. 248-269.

1985b Essai

pour une typologie de la cloche tibétaine dril-bu, Arts Asiatiques, vol.

40 (1985b), pp. 53-67.

MAHDIHASSAN, S.

1991 Indian

Alchemy or Rasayana in the Light of Asceticism and Geriatrics, Motilal Banarsidass (Delhi 1991).

MKHAS-GRUB-RJE DGE-LEGS-DPAL-BZANG (1385-1438)

199x Rdo-rje Theg-pa’i Lam-gyi Yan-lag

Mi-’bral-ba dang Bsten-par Bya-ba’i Dam-tshig-gi Rdzas Med-du-mi-rung-ba-dag-gi

Mtshan-nyid dang / Ji-ltar Bcad-pa’i Tshul la sogs-pa Rnam-par Bshad-pa

Rnal-’byor Rol-pa’i Dga’-ston [‘Yogis’

Acting Festival: A Detailed Explanation of Such Matters as the Characteristics

and Methods for the Holding of the Indispensible Commitment Substances which

are, in the Branch Vows of the Vajra Vehicle’s Path, Never to be Parted from,

and Are to be Put to Use’], as contained in: Collected Works of

Mkhas-grub-rje, as contained in: Rje Yab-sras Gsum-gyi

Gsung-’bum [impressions from the 19th

century Sku-’bum Byams-pa-gling woodblocks] (Kumbum Monastery 199x), vol. 15 (ba), pp. 205-344. CD digital reproductions supplied by

Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (New York).

PANISH, CHARLES K.

1968 Tibetan Paper

Money, Whitman Numismatic Journal, vol.

5, no. 8 (1968), pp. 467-471; vol. 5, no. 9 (1968), pp. 501-508.

SKORUPSKI, TADEUSZ

1996 The

Saṃpuṭa-tantra: Sanskrit and Tibetan Versions of Chapter One, contained in: T.

Skorupski, ed., The Buddhist Forum, Volume IV: Seminar Papers 1994-1996, School of Oriental and African Studies (London

1996), pp. 191-244.

SMITH, R. MORTON

1988 Using

Makaras, contained in: S.K. Maity, Upendra Thakur and A.K. Narain, eds., Studies

in Orientology: Essays in Memory of Prof. A.L. Basham, Y.K. Publishers (Agra 1988), pp. 150-155.

SNELLGROVE, DAVID

1987 Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Shambhala Publications (Boston

1987).

STEIN, ROLF ALFRED

1977 La gueule du Makara: un trait inexpliqué de

certains objets rituels, contained in:

A. Macdonald and Y. Imaeda, ed., Essais sur l’art du Tibet, Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient

(Paris 1977), pp. 52-62.

VIENNOT, ODETTE

1954 Typologie du makara et essai de chronologie, Arts

Asiatiques, vol.

1, no. 3 (1954), pp. 189-208.

1958 Le

makara dans la décoration des monuments

de l’Inde ancienne: positions et fonctions, Arts Asiatiques, vol. 5, no. 3-4 (1958), pp. 183-206, 272-292.

VOGEL, J.P.

1924 De

Makara in de Voor-Indische Beeldhouwkunst, Nederlandsch-Indië, Oud en Nieuw, vol. 8, no. 9 (January 1924), pp. 262-276.

1930 Le

Makara dans la sculpture de l’Inde,

“extrait de la Revue des Arts Asiatiques,” Les Éditions G. van Oest (Paris

1930).

1957 Errors

in Sanskrit Dictionaries, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African

Studies, vol. 20, nos. 1-3 (1957), pp.

561-567.

WADDELL, L. AUSTINE

1988 Lhasa and Its

Mysteries, with a Record of the British Tibetan Expedition of 1903-1904, Dover Publications (New York

1988), originally published in 1905. Download it here for free if you like.