|

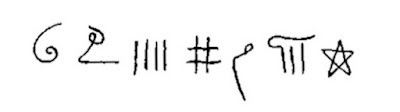

| Seven Seals (as seen in Arabic magic, read from right to left) |

(*For instance in this blog entry: To Bind a Book is to Protect It from the Elements.)

The bigger puzzle, one that may not prove solvable, is whether somehow two different sets of seven, specifically the Solomonic magic and the Perfection of Wisdom sets may have come together to help create something new in the early Zhijé understanding. I thought I should do you the courtesy of telling you what I’m now thinking right off the bat. Expecting to fall short of a defendable conclusion on that more ambitious question, I thought that today I’d start by going into how different Tibetan-language sources understood the Seven Seals to mean. One of the most prominent among them is in some sense of the word codicological, which is surprising, surprising even if we have to know that it only surfaces in contexts where scrolls or codex or pothi forms of books are implicated. To put it simply, the thing that requires extra sealing security is a book, a book regardless of the shape it takes.*

(*I’m thinking here of the sets of Revelation and the Perfection of Wisdom scriptures, as the set in Solomonic magic is usually associated with rings and amulets rather than books. For some suggestively parallel early Christian images of enthroned books and scrolls with seven seals attached, have a look at the illustrations to the article by Armin Bergmeier that ought to be downloadable HERE. In case the link stops working, schmoogle for the title “Volatile Images: The Empty Throne and its Place in the Byzantine Last Judgment Iconography.”)

Some Tibetans interpret the Seven Seals to be a set of things that in some sense bind the parts of the written composition, and not only its volume, together. How can that possibly be? you may ask.

Well, first of all you have to give up that idea so engrained in many moderns that a book binding must mean two cover boards joined together by a labeled spine with all the pages threaded together and glued on to it. Of course that disputably ‘normal’ object is included in the category, but bindings can be so much more. In Tibetan minds during recent centuries, we would have to understand first of all the binding elements like the two boards, the strap, the cloth cover and cloth label. But then we could go on to include anything that helps keep any element of the text and volume from getting out of order or damaged. And that goes all the way down to the letters and syllables, the scoring lines, the sentence punctuations and the fascicles (for want of a better word). It’s all about protection, but protection against the entire gamut of forces that might interfere with the continuing usefulness of the book. In terms of traditional physics, that would mean the four elements.* Books aren’t alone in their vulnerabilities, as both bodily ailments and natural disasters could all be assigned by traditional sciences to elemental disturbance and disruption. They still might.

(*I’m just generalizing here as I’ve written about the element protecting function of the binding elements in much greater detail in the blog entry linked above.)

So to return to our subject, the Seven Seals were variously understood by Tibetans of time past. Our task of elucidation is greatly aided by looking into the new Tibetan grammar by Sangyela of the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala. I make use of the 2012 edition, as it seems to be a lot more extensive than the 2005. The Tibetan-letter text for it can be found below if you are looking for it. Here is Sangyela’s list, with his brief explanation just before it:

“So then, if you want to know what these seven levels of seals might be, they are seven seals that are affixed in order to avoid mixups: As these concern the verbal significances of textbooks, no matter which of the sciences they belong to, that means mixups of higher and lower, earlier and later, front and behind, right and left.

- ཚེག་བར་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ཚེག་གི་རྒྱ། The seal of the syllable punctuation point, the tsheg, prevents confusion of syllables.

- གཅོད་མཚམས་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ཤད་ཀྱི་རྒྱ། The sentence and clause (etc.) punctuation mark, the shad, prevents confusion of [grammatical/syntactical] boundaries.

- དོན་ཚན་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ལེའུའི་རྒྱ། The chapter (le'u) seal prevents confusion of subject-matters.

- གཞུང་ཚད་རྟོགས་པ་བམ་པོའི་རྒྱ། The seal of the fascicle (bam-po) creates understanding of text length.

- བམ་པོ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་བམ་གྲངས་ཀྱི་རྒྱ། The seal of the fascicle number prevents confusion of fascicles (bam-po).

- མཐའ་མི་འཆོལ་བ་སྣེ་ཐིག་གི་རྒྱ། The margin scoring lines (sne-thig) prevent confusion of the ends [of the lines].

- གླེགས་བམ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་གདོང་ཡིག་གམ་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་གྱི་རྒྱ་བཅས་སོ།། The seal of the running header (spyan-khyer) or the front label (gdong-yig) prevent the Volume from getting out of order.”

(*Seal no. 7, although the running header is not quite so essential in a modern stitched codex as it is in a pothi where pages might even be returned to the wrong book thanks to ignorance or negligence, and so require some serious sorting out).

Sangyela quotes several sources on the Seven Seals, including Dungkar Rinpoche (1927-1997) in his wellknown Encyclopedic Dictionary published in 2002. Another is Padma-rgyal-mtshan’s grammar of 2000. He mentions, too, a list in one of the works by the modern author Sems-dpa'-rdo-rje (b. 1926), and quotes the famous modern Nyingma teacher 'Jigs-med-phun-tshogs (1933-2004). Not mentioned by him is Dpa’-ris Sangs-rgyas’ 1998 grammar. It is true of all of them that they do not name any source of their information (and Sangyela mentions this himself on p. 479), but I hope it is fairly clear that all of these works mentioned so far are dating from years closely surrounding 2000. And to underscore the problem, we have to say that searching for keywords in the huge database of TBRC came up with a single earlier parallel listing of the Seven Seals as we found in those two-decade-old works.

The single exception is the work of the Mongolian-born Bstan-dar Lha-rams-pa (1754-1840, for details see bibliography) brought to my attention by Gedun Rabsal. I give my complete translation of the passage that I made before realizing it had been translated into English already by Don Lopez Jr. (q.v.). I put it all in blue so you can see where it begins and ends. If you want the Tibetan text, look in the bibliography:

The expression ‘sealing with the seven layers of seals’ refers to this:

- To keep the syllables unconfused, the seal of the tsheg.

- Keeping the pādas unconfused, the seal of the shad.

- Keeping the word meanings unconfused, the seal of the chapter.

- Keeping the śloka-verses unconfused, the seal of the bam-po.

- Keeping the bam-po unconfused, the seal of the bam-po numbers.

- Keeping the edges unconfused, the seal of the scoring lines.

- Keeping the Volume unconfused, the seal of the end label or the page header.

Some put it this way:

1. The seal of all seven of the binding strings.

2. The seal of binding boards and leaves.

3. The seal of gold label and lañtsa script.

4. The seal of the head letter and numerals.

5. The seal of bam-po and chapters.

6. The seal of scoring lines and page headers.

7. The seal of red and black shad.*

(*My note: I think red shad intends the double shad that is often called kar-shad, or ‘white shad.’ Black shad means the single shad.)

This spyan-khyer means the book’s running title [my note: the front title in a much-abbreviated form]. It appears at the small end of the page of a Volume either before or after the page number.

The Ornament Light* says, “When [the Volume] is tightly bound up in seven sashes, in the seven places where the knots are, seals bearing their own names [or Dharmodgata’s own name] are attached and left there, or so some say.”

As far as I am able to tell, I think if we consider the Volumes translated in early Tibet and what appears in the Great Commentary on the Eight Thousand,* this could have been the appropriate thing to do in the case of Volumes in India. This is something scholars should look into.

(*Both Ornament Light (Rgyan-snang) and Great Commentary on the Eight Thousand I believe mean the same work by Dbyangs-can-dga’-ba’i-blo-gros (1740-1827), 'Phags-pa Brgyad-stong-ba'i 'Grel-chen Rgyan-snang-las Btus-pa’i Nyer-mkho Mdo Don Lta-ba’i Mig-’byed, although both could also mean the more famous commentary that came before it, the one by Haribhadra. The passage in rough Wylie transcribed etext is as follows: rgya rim pa bdun gyi rgyu sa btab nas bzhag ces pa la [437] 'grel chen du/_rgya rim pa bdun gyis btab nas zhes bya ba ni rnyed dka' zhing don_che ba nyid kyis/_'di 'a gus pa bskyed par bya ba'i don du sku rags bdun gyis shin tu dam par bcings nas mdud pa'i gnas bdun la rang gi mi _nga gi rgya bdun gyi rgyas btab nas bzhag pa yin no zhes kha cig gis 'dod do/_/zhes gsungs shing bshad tshul gzhan ma bkod pas na slob dpon gyis rang lugs la'ang bzhed de/_ _n+de thams cad mkhyen pa sa kyang rgyal sras rtag tu ngu'i rtogs brjod las/_chos 'phags kyi sku rags_ bdun bdun gyis shin tu dam par bcings nas mdud pa'i gnas bdun la rang ming gi rgya rim pa bdun gyis btab nas bzhag pas zhes gsungs so/_/_gnad kyi zla 'od las/_chings ma bdun gyi mdud pa bdun la rang gi ming gi rgya rnams kyis rgyas btab pa'o/_/zhes 'byung ngo /_/de ni glegs bam rnams sku rags bdun bdun gyis bcings nas/_sku rags re'i mdud mtshams la chos 'phags rang ming gi mtshan ma yod pa'i rgya re btab pas na rgya rim pa bdun gyi rgyas btab pa zhes pa yin no/_/)

Given the lack of visible antiquity, there are a number of possible ways to save the situation, the first that comes to mind is that at least one of the modern authors had an orally transmitted instruction on this point that could theoretically be as old as time itself. But I’m not necessarily willing to make that argument, so I draw the consequence that the listing came into being when it came into print. That would mean that these cannot have been in the mind of Atiśa when he listed the Seven Seals as one among the several bookbinding elements in his Consecration text. Rather Atiśa would have been thinking of the (wax) seals themselves as we know them from the Prajñāpāramitā, used to keep the Volume as a whole secure and inviolable as befits a holy object.

If we think about it, it would have been quite impossible for an Indian like Atiśa to intend the list we've given above as it includes the tsheg syllable dividing mark and the bam-po divisions of manuscripts that were not known in India, well, certainly not in the same form. And I think the same would hold true of Padampa’s idea of the Seven Seals which is quite distinct. Of course every mention of the Seven Seals in Tibetan Buddhist culture descends from the Prajñāpāramitā passage, or from writers attempting to explain or account for it. It could be, too, that Bstan-dar and the ca. 2000 CE grammarians were attempting in their own way to account for the presence of the Seven Seals in Atiśa’s list of binding elements. If some perplexity remains, I think we can leave it aside for awhile to look a little more closely at the Zhijé listing dating to ca. 1245 CE that we considered in the last blog. Here is the page in question once more:

| Zhijé Collection, vol. 1, p. 158 (click to expand or go to the link) |

The seven seals named here are: 1. zab rgya. 2. gces rgya. 3. gsang rgya. 4. gab rgya. 5. gtad rgya. 6. rtsis rgya. 7. bsna rgya.*

(*For comparison, the seals as they appear in the same volume, p. 148: zab rgya / ces rgya / gsang rgya / rtsis rgya / gtad rgya / mna' rgya / gab rgya / rgya rim pa bdun gyis btab bo. This other list suggests that no. 7 ought to be read as mna' rgya, or Oath Seal.)

Without help of commentary, here is what I think these names mean: 1. Profundity Seal. 2. Affection (Love) Seal. 3. Secret Seal. 4. Concealed Seal. 5. Entrustment Seal. 6. Calculation (Estimation) Seal. 7. Various (Everything? Oath?) Seal.

If you are thinking there may be no reason to think these Seven Seals connect to the Buddhist scriptural Seven Seals you can wipe that doubt from your head. The text is a brief one, part of a series of texts likely composed around 1200 CE and devoted to abhiṣeka rites in which we find very explicitly described the setup of the book shrine from the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras. The mental association is not in doubt.

How does all this evidence make sense historically? To keep matters simpler, I have overlooked a few eccentric interpretations of the Seven Seals that emerged in the six centuries between around 1200 and the work by Bstan-dar in around 1800. They do hold some significance for my argument because they yield no evidence of understanding them as individual binding elements (so have a look at the Appendix below if you like). This fuller version surfaces only in around 1800 as far as I can know, although the seeds of it are arguably there in the Atiśa consecration text (in the most general way, and without any of the details).

So what I’m suggesting would help explain the inspiration for the colophonic sealing expressions in that ca. 1200 text in the ca. 1245 manuscript of the Zhijé Collection are these factors: First and foremost the sacred Volume of the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras. These scriptures are quite central to the Zhijé tradition as a whole from its beginnings, so there are no grounds for wonder. But secondly and less obviously, it is likely that this Zhijé understanding was influenced or affected by some tradition of Solomonic magic’s Seven Seals. The exact hows and whys are not well explored, so we leave that for future studies to go into in some depth. The smoking gun is that Arabo-Persian word for seal (discussed in the last blog) right next to the seven-fold list. That it is there demonstrates likely awareness of the set of Seven Seals known in the Arabo-Persian world at the time. Thirdly and lastly, it is unlikely that the Zhijé author held any knowledge or understanding of the Seven Seals in the Book of Revelations, or bears any trace of connection with it, or shares one iota of its apocalyptic context. And I think that holds even if we accept Conze’s idea of a Gnostic connection in late antiquity that could link the set in Revelations with the set in the Perfection of Wisdom. And I think it holds even if we accept Graham’s idea that Revelations’ set and the Solomonic magical set are linked by their color symbolisms (or correspondences with planets or planetary spheres).

So to put it simply: What underlies or inspires the Zhijé set of Seven Seals? The Perfection of Wisdom sūtras? Absolutely yes. The set found in late Solomonic magic? Likely. The set in Revelations? Likely not, even if historically remote factors could have entered into the mix somewhere along the line.

Well, that about finishes everything I thought I was ready to say about the subject, so I’ll leave it for now. Not that I think that seals it.

- I can’t believe you have nothing to say, so if you would be so kind, leave a comment and let’s talk about it, friend-to-friend.

§ § §

Read more and reconsider what we thought we knew

Atiśa (982-1054), Consecration of Body, Speech and Mind [Icons], Kāyavākcittasupratiṣṭhā (Sku dang Gsung dang Thugs Rab-tu Gnas-pa), translated by the author and his disciple Rgya Brtson-’grus-seng-ge, Dergé Tanjur, vol. ZI, folios 254-260 (or Tôhoku catalogue no. 2496). For its inclusion of the Seven Seals in its list of binding elements, see this earlier Tibeto-logic blog, in the chart near the end.

For more on this text (but without ever mentioning its use of the Seven Seals), see D. Martin, “Atiśa’s Ritual Methods for Making Buddhist Art Holy,” contained in: Shashibala, ed., Atiśa Śrī Dīpaṅkara-jñāna and Cultural Renaissance: Proceedings of the International Conference, 16th-23rd January 2013, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (New Delhi 2018), pp. 123-138. But this article, like others in the volume, is riddled with editorial errors. So you would be well advised to download the PDF at academia.edu.

རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་གྱིས་རྒྱས་བཏབ་ཅེས་པ་ནི།1. ཡིག་འབྲུ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ཚེག་གི་རྒྱ།2. ཚིག་རྐང་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ཤད་ཀྱི་རྒྱ།3. ཚིག་དོན་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ལེའུའི་རྒྱ།4. ཤོ་ལོ་ཀ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་བམ་པོའི་རྒྱ།5. བམ་པོ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་བམ་གྲངས་ཀྱི་རྒྱ།6. མཐའ་མི་འཆོལ་བ་སྣེ་ཐིག་གི་རྒྱ།7. གླེགས་བམ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་གདོང་ཡིག་གམ་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་གྱི་རྒྱ་དང་བདུན་ནོ། །ཁ་ཅིག་གིས།1. གླེགས་ཐག་བདུན་པའི་རྒྱ།2. གླེགས་ཤིང་པ་ཊའི་རྒྱ།3. གསེར་གདོང་ལཉྩའི་རྒྱ།4. ཡིག་མགོ་གྲངས་ཀྱི་རྒྱ།5. བམ་པོ་ལེའུའི་རྒྱ།6. སྣེ་ཐིག་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་གྱི་རྒྱ།7. དམར་ཤད་ནག་ཤད་ཀྱི་རྒྱ་དང་བདུན་ཟེར་རོ། །དེའི་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་ནི་གླེགས་བམ་གྱི་སྣེ་མོའི་གྲངས་ཡིག་གི་གོང་འོག་གང་རུང་དུ་དཔེ་ཆའི་མིང་བྲིས་པ་ལ་ཟེར།རྒྱན་སྣང་ལས།སྐེ་རགས་བདུན་གྱིས་དམ་པོར་བཅིངས་ནས་མདུད་པའི་གནས་བདུན་ལ་རང་གི་མིང་གི་རྒྱ་བདུན་གྱིས་བཏབ་ནས་བཞག་པ་ཡིན་ནོ་ཞེས་ཁ་ཅིག་གིས་འདོད་དོ། །ཞེས་བྱུང་ངོ་། །ཁོ་བོའི་བསམ་ཚོད་ལ། སྔ་མ་བོད་དུ་བསྒྱུར་པའི་གླེགས་བམ་གྱི་དབང་དུ་བྱས་པ་དང་། བརྒྱད་སྟོང་འགྲེལ་ཆེན་ལས་བྱུང་བ་ནི་འཕགས་ཡུལ་གྱི་གླེགས་བམ་གྱི་དབང་དུ་བྱས་པ་ཡིན་བྱས་ན་རུང་ནམ་སྙམ་ཞིང་མཁས་པས་དཔྱད་པར་བྱའོ། །

Since this passage about the book with seven seals is absent from the earliest Chinese translations, Conze believed it was added later, as late as around 250 CE. He therefore believed the most likely source of the commonality was some mystical or gnostic tradition of Mediterranean origins, and not very likely but possibly a borrowing by the Buddhists from [the late 1st-century?] Book of Revelations composed on the island of Patmos.

གཞན་ཡང་། རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་ནི། ཚེག་ཁྱིམ་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་ཚེག་གི་རྒྱ། ཚིག་རྐང་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་ཤད་ཀྱི་རྒྱ། བརྗོད་དོན་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་ལེའུའི་རྒྱ། ཤོ་ལོ་ཀ་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་བམ་པོའི་རྒྱ། བམ་པོ་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་བམ་པོའི་གྲངས་ཀྱི་རྒྱ། མཐའ་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་སྣེ་ཐིག་གི་རྒྱ། གླེགས་བམ་མི་འཁྲུག་པ་གདོང་ཡིག་གམ་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་གྱི་རྒྱ་རྣམས་ཡིན། ཚིགས་བཅད་ཀྱི་རྐང་བ་བཞིའམ། ཚིག་ལྷུགས་ཀྱི་ཚེག་དབར་སུམ་ཅུ་སོ་གཉིས་ ༼སླ་རྩིས་སུ་ཚེག་དབར་སུམ་ཅུ་༽ ལ་ཤོ་ལོ་ཀ་གཅིག་དང་། ཤོ་ལོ་ཀ་སུམ་བརྒྱ་ལ་བམ་པོ་གཅིག་ཏུ་བརྩིས་པ་དང་། པོ་ཏི་ཆེ་བ་ལ་ཤོག་གྲངས་ལྔ་བརྒྱ་དང་། འབྲིང་བ་ལ་ཤོག་གྲངས་བཞི་བརྒྱ་ཡས་མས་དང་། ཆུང་བ་ལ་ཤོག་གྲངས་ཉིས་བརྒྱ་ནས་སུམ་བརྒྱའི་བར་ཡིན་ནོ།།

Dungkar Rinpoche’s encyclopedic dictionary — Mkhas-dbang Dung-dkar Blo-bzang-'phrin-las Mchog-gis mdzad-pa'i Bod Rig-pa'i Tshig-mdzod Chen-mo Shes-bya Rab-gsal, Krung-go'i Bod Rig-pa Dpe-skrun-khang (Beijing 2002).

On pp. 584-585 are two relevant entries, “Glegs-bam” and “Glegs-bam-gyi Rgya Rim-pa Bdun.” The first entry has a set of “Special Characteristics of [Scriptural] Volumes” that is remarkable for including not only margin marking lines etc., but also (nos. 5-7) binding boards, binding straps, and book wrapper. The second entry is the more expected version of the Seven Seals. No source is named for either list, so that we might even feel like we can take them to be the Rinpoche’s original ideas. Both lists are used, with acknowledgement, in Nor-brang's numerological dictionary, so going there isn’t necessary.

Asher Eder, The Star of David: An Ancient Symbol of Integration, Rubin Mass Ltd. (Jerusalem 1987).

It isn’t just that I happened to have this book in my home library for decades now. It is written from a perspective of a Judaism that is religiously sensitive yet quite educated and broad minded. The author has been much involved in interfaith dialog, particularly Islam-Judaism dialog. It is interesting that not even once are the Seven Seals mentioned, even though this is a very likely proximate source of the modern Zionist national symbol featured on the Israeli flag. That it wasn’t always so ought to go without saying. Although not such a problem in this book, we have to be aware and wary of nationalist approaches that dredge through the past to find presently useful bits, and doing this with an utter disregard for meanings those things held in the past.

Helmut Eimer, “Remarks on the Bam-po Numbers in the Extensive Tibetan Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra,” contained in: Facets of Indian Culture: Gustav Roth Felicitation Volume (Patna 1988), pp. 465-472.

You might see also Ernst Steinkellner, “Paralokasiddhi-Texts,” contained in: Buddhism and Its Relation to Other Religions: Essays in Honour of Dr. Shozen Kumoi on His Seventieth Birthday (Kyoto 1985), pp. 215-224. Most recently: Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp, “Some Remarks on the Meaning and Use of the Tibetan Word bam po,” Zangxue xuekan (Journal of Tibetology), vol. 5 (2009), pp. 114-132. I suppose if you study all these essays you ought to gain a good idea what a bam-po might be and why there needs to be such a thing.

Annabel Teh Gallop, “The Ring of Solomon in Southeast Asia.” Posted on the British Library website on November 27, 2019.

This not only nicely explains the relationship between Solomon’s ring and the seven seals, even more interestingly for present purposes, it illustrates and demonstrates yet another example of Buddhist-Islamic exchange in the field of magic and magical diagrams (yantras).

Edgar J. Goodspeed, “The Book with Seven Seals,” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 22, no. 1 (1903), pp. 70-74.

This says the book in Revelation is a codex, and not a scroll, with the seals on its back so that it could not be opened, its content kept secret. And even if this may also go without saying, all seven of them must be broken to gain access. If the seals were not serving some metaphoric purpose or corresponding to seven different actions, then there would be no advantage in having seven of them, since one seal would accomplish the task just as well as seven. Sometimes it is helpful to contemplate the obvious, no doubt. And it is good to know that the symbolisms, meanings and purposes of the seven seals in medieval Europe could be quite varied and speculative (see also Gumerlock).

Lloyd D. Graham, “A Comparison of the Seven Seals in Islamic Esotericism and Jewish Kabbalah.” Posted at Academia.edu.

———. “The Seven Seals of Judeo-Islamic Magic: Possible Origins of the Symbols.” Posted at academia.edu. There are more relevant essays by this same author that I haven’t listed here. You can download many or most of them by going here.

———. “The Seven Seals of Revelation and the Seven Classical Planets,” The Esoteric Quarterly (Summer 2010), pp. 45-58.

Here you can see a Jewish magical version of the Seven Seals that partly resembles the Arabic, but doesn’t even have a star, although square, circle and spiral it does have. Actually, the square stands in place of the star, which seems bizarre. Although a bit complicated and largely based on color associations, there is an argument made here about the Seven Seals of both Revelations and late Middle Eastern (Hebrew and Arabic) magic corresponding to the seven planets. In some contexts, the Seven Seals may allow passage through the planetary spheres. This doesn't seem to even remotely apply to the Seven Seals in Great Vehicle Buddhism. At least I can’t see it.

Francis X. Gumerlock, The Seven Seals of the Apocalypse: Medieval Texts in Translation, Medieval Institute Publications (Kalamazoo 2009).

Filip Holm, “Talismanic Magic in the Islamicate World.” See it at YouTube.

Michael Lockwood, “Prajñāpāramitā and Sophia: Heteropaternal Superfecundated Twins” (Sept. 5, 2019). PDF from internet. Particularly p. 12.

Lockwood reproduces not only Conze’s article, but a large section of the book by H. Ringgren that Conze was reviewing in his article, making both works more accessible. In case you’re as perplexed by the term as I was, I recommend a Schmoogle search for “Heteropaternal Superfecundated Twins.”

Donald S. Lopez Jr., “Chapter 10: Commentary on the Heart Sûtra, Jewel Light Illuminating the Meaning by bsTan-dar-lha-ram-pa,” contained in: The Heart Sûtra Explained: Indian and Tibetan Commentaries, Sri Satguru Publications (Delhi 1990), pp. 139-159. The passage of Bstan-dar Lha-rams-pa, q.v., is translated quite nicely on p. 146.

Christian Luczanits, “In Search of the Perfection of Wisdom: A Short Note on the Third Narrative Depicted in the Tabo Main Temple,” contained in: Eli Franco & Monika Zin, eds., From Turfan to Ajanta: Festschrift for Dieter Schlingloff on the Occasion of His Eigtieth Birthday, Lumbini International Research Institute (Lumbini 2010), vol. 2, pp. 567-578.

Douglas W. Lumsden, And Then the End Will Come: Early Latin Christian Interpretations of the Opening of the Seven Seals, Garland (New York 2001). Not seen, but likely to be relevant, if not now in some future blogosphere.

O-rgyan-gling-pa (b. 1323), treasure finder, Bka’-thang Sde Lnga, Mi-rigs Dpe-skrun-khang (Beijing 1990). If you have some other edition, it doesn't matter, since the sealing expressions ought to appear very near the ends of each of the five major sections. In each case there are Five Seals and not Seven. Here is a sample set of its sealing expressions:

ས་མཱ་ཡ། རྒྱ་རྒྱ་རྒྱ། གཏེར་རྒྱ། སྦས་རྒྱ། གསང་རྒྱ། གབ་རྒྱ། གཏད་རྒྱ།

In my own understanding these five were chosen out from the seven because of their resonance within the gter-ma tradition: gter [underground treasure, treasure text] seal, concealment seal, secrecy seal, hiding [covered up] seal, and entrustment seal.

Padma-rgyal-mtshan (1956-2001), Gleng-brjod Chen-mo 'Dzam-gling Rgyan-gcig. The author may be called 'Gos Padma-rgyal-mtshan or Rig-gnas-smra-ba'i-dbang-phyug. This work, completed in the year 2000, is available at TBRC no. W1KG15962, but I was unable to get inside of it to locate the passage that Sangyela (p. 504) quotes as follows:

༈ ཡང་གླེགས་བམ་བཞེངས་དུས་རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་གྱི་བཀས་བཅད་ཡོད་པ་ནི། ཚིག་འབྲུ་མཐར་མི་འཆོལ་བ་སྣེ་ཐིག་གི་རྒྱ། ཚིག་འབྲུ་མི་འཆོལ་བ་ཚེག་གི་རྒྱ། གཅོད་མཚམས་མི་འཆོལ་བ་ཤད་ཀྱི་རྒྱ། རྒྱབ་མདུན་མི་འཆོལ་བ་ཡིག་མགོའི་རྒྱ། གླེགས་བམ་མི་འཆོལ་བ་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་གྱི་རྒྱ། ཚིག་དོན་མི་འཆོལ་བ་ལེའུའི་རྒྱ། གཞུང་ཚད་རྟོགས་པ་བམ་པོའི་རྒྱ་བདུན་ནམ་ཡང་ན་ཡིག་མགོའི་རྒྱ་མེད་པར་བམ་པོ་མི་འཆོལ་བ་བམ་གྲངས་ཀྱི་རྒྱ་ཞེས་བདུན་ནོ་།། །།

Venetia Porter, Liana Saif, and Emilie Savage-Smith, “Medieval Islamic Amulets, Talismans, and Magic,” contained in: Finbarr Barry Flood and Gülru Necipoglu, eds., A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, John Wiley & Sons (London 2017), pp. 521-557.

For a remarkable example of the seven figures inscribed in reverse on a carnelian sealstone, see fig. 21.7 on p. 541. The explanation for the seven found on the following page, a translation from al-Buni, is remarkably clear, if still puzzling.

Tsepak Rigzin (Tshe-dpag-rig-’dzin), Nang-don Rig-pa'i Ming-tshig Bod Dbyin Shan-sbyar [Tibetan-English Dictionary of Buddhist Terminology], revised and enlarged edition, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (Dharamsala 1993).

Here, in the entry “རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་” on p. 53, you may find a listing of “the seven codes of translation.” The Tibetan is fine, but the English translations are entirely off. And I have to say, if the early Tibetan translators were made to follow all of these supposed rules they would have never completed a single page.

Sangyela (Na-ga Sangs-rgyas-bstan-dar, ན་ག་སངས་རྒྱས་བསྟན་དར་), Bod-kyi Brda-sprod Nag-ṭīkāḥ (བོད་ཀྱི་བརྡ་སྤྲོད་ནག་ཊིཀཿ), Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (Dharamsala 2012), section entitled “Rgya Rim-pa Bdun Rgya-cher Bshad-pa,” at pp. 477-504 (The following selection from it is copied on the basis of the BDRC digital assets, the core passage is this one):

རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་རྒྱ་ཆེར་བཤད་པ།

(I’ve omitted several initial paragraphs that lead up to the main discussion, and have left off the detailed discussion of each ‘seal’ that comes after it.)

འོ་ན། རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་ཞེས་པ་གང་དང་གང་ཡིན་ཟེར་ན། རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་ནི་རིག་པའི་གནས་གང་ཡང་རུང་བའི་གཞུང་གི་ཚིག་དོན་གོང་འོག་སྔ་ཕྱི་རྒྱབ་མདུན་གཡས་གཡོན་གྱི་སྣེ་སོགས་མི་འཆོལ་བའི་ཆེད་དུ་གདབ་པའི་རྒྱ་བདུན་ཏེ།

༡ ཚེག་བར་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ཚེག་གི་རྒྱ།

༢ གཅོད་མཚམས་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ཤད་ཀྱི་རྒྱ།

༣ དོན་ཚན་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་ལེའུའི་རྒྱ།

༤ གཞུང་ཚད་རྟོགས་པ་བམ་པོའི་རྒྱ།

༥ བམ་པོ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་བམ་གྲངས་ཀྱི་རྒྱ།

༦ མཐའ་མི་འཆོལ་བ་སྣེ་ཐིག་གི་རྒྱ། [479]

༧ གླེགས་བམ་མི་འཁྲུགས་པ་གདོང་ཡིག་གམ་སྤྱན་ཁྱེར་གྱི་རྒྱ་བཅས་སོ།།

གོང་གསལ་རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་གྱི་གྲངས་འདྲེན་ནི་བོད་རྒྱ་ཚིག་མཛོད་ཆེན་མོ་དང་། སློབ་དཔོན་ཆེན་པོ་སེམས་དཔའ་རྡོ་རྗེས་བགྲངས་པའི་རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་གྱི་གྲངས་འདྲེན། དུང་དཀར་ཚིག་མཛོད་ཆེན་མོ། བརྡ་སྤྲོད་པའི་གྲུབ་མཐའི་གླེང་བརྗོད་རྣམས་སུ་ལུང་ཁུངས་ཀྱི ས་དབེན་པའི་གྲངས་འདྲེན་རྣམས་ལ་རང་ངོས་ནས་བསམ་ཞིབ་ནན་ཏན་གྱིས་ཞལ་གསལ་དུ་བཏང་བ་དང་ཞུས་དག་བགྱིས་ཏེ་འདིར་བཀོད་པ་ལགས་སོ། །གོང་གི་ཕྱག་དཔེ་རྣམས་སུ་རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་གྱི་གྲངས་འདྲེན་ཙམ་དང་། འགའ་ཞིག་ཐད་ཚིག་སྦྱོར་ཡང་གོ་མ་བདེ་འདུག་པས་གཞུང་གི་དཀྱུས་སུ་མ་བཀོད་པས་དོན་དུ་ལྷག་ཆད་ནོར་བའི་སྐྱོན་གསུམ་དང་ལྡན་པས་ན་རང་སོར་གཞག་རྒྱུ་ལེགས་བཤད་དུ་མ་མཐོང་། འོན་ཀྱང་འབྱུང་འགྱུར་ཉམས་ཞིབ་ཀྱི་སླད་དུ་འདི་མཉམ་ལྷན་ཐབས་སུ་བཀོད་པ་དེར་གཟིགས་གནང་ཞུ།།

Go here and then scroll down to chapter 85. You will find the Seven Seals at paragraph 85.57.

Shaba (or sheba) is related to either “oath” or “seven,” where the number refers to the proverbial seven seals or seven bonds (of an oath). The letter yod in between joins the two words in construct or acts as the possessive pronoun “my,” resulting in these possible meanings of the name: “God of oathing,” “God of the seven,” or “(my) god is an oath.”

The relation between oaths or vows and seals is an interesting one to contemplate, especially given that the word samaya (in Tibetan letters, sa-ma-ya or ས་མ་ཡ་) is a frequent ‘sealing word’ quite liable to be placed at the end of a text regarded as secret. Here for example is a set of sealing expressions written in an encoded script.

Perhaps you can read it? I suggest this: sa-ma-ya :

gu-hya a (?) tham rgya : sku gsung thug[s] rgya : a tham :

The first three syllables you see here are sa-ma-ya, clearly, despite the encoded way of writing, while the remaining parts are still more sealing expressions in that same occult script. This was found at the end of a set of Nyingma magical texts found near Dergé in Eastern Tibet, and I shouldn’t tell you which one. To go ahead and say what I wanted to say here: It is possible that in some language somewhere, and very likely one of the Semitic tongues, there were two similar-sounding words that meant ‘seven’ and ‘oath.’ Well, at least it’s food for thought. Perhaps numerology wasn’t the only reason for the seven-ness of the seals. Did I mention the Seven Sleepers? The Seven Sages?

Appendix

Early discussions found via BDRC/BUDA searches:

From a work by ’Jig-rten-mgon-po (1143-1217 CE):

The group of seven levels of seals means the six sense consciousnesses with the afflicted mind (kliṣṭamanas) being seventh.

རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་པོ་དེ་ནི་རྣམ་ཤེས་ཚོགས་དྲུག་ཉོན་མོངས་པ་ཅན་གྱི་ཡིད་དང་བདུན་ཡིན་གསུངས།། །།

- About seven passages can be located in his Collected Works, his Bka’-’bum, this being only one of them. The set of consciousnesses named here suggests association with the works of Asaṅga and the Yogācara school.

_ _ _

From a work by 'Brug-chen Padma-dkar-po (1527-1596):

- This source is quite alone and distinct in associating the seven seals with [1] the pronouncer of the scripture, [2] the compiler, [3-5] the bodies, speeches and minds of the Skygoers, [6] the Lama and [7] the Dharma Protectors.

རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་ནི། གསུང་བ་པོ་སངས་རྒྱས་ཀྱི་བཀའ་རྒྱས་བཏབ་པ་དང་གཅིག །སྡུད་པ་པོས་ཕྱག་རྒྱས་གཏབ་པ་དང་གཉིས། ཌཱ་ཀི་མ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་སྐུ་གསུང་ཐུགས་གསུམ་གྱི་ཕྱག་རྒྱས་བཏབ་པ་དང་ལྔ། བླ་མ་རྣམས་ཀྱི་བཀའ་རྒྱས་བཏབ་པ་དང་དྲུག །ཆོས་སྲུང་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་བསྲུང་བའི་རྒྱས་བཏབ་པ་དང་བདུན་ཞེས་འབྱུང་སྟེ། གསུང་བ་པོའི་རྒྱ་ནི་རྡོ་རྗེར་འཆང་ཚེ་དཔལ་ཧེ་རུ་ཀ་ཉིད་ཀྱིའོ།།

_ _ _

From a work by Dbyangs-can-dga’-ba’i-blo-gros (1740-1827):

- It quotes from Abhayākaragupta's (early to mid 12th century CE) Marmakaumudī, an early-to-mid 12th century commentary on the Eight Thousand Prajñāpāramitā, and this quote may in fact be found in its Tibetan translation contained in the Tanjur.

The Moonlight of Essential Points says, “On each of the seven knots in the seven binding straps he attached a seal with his own name.” That means they bound up their Volumes with seven sashes each, and then on each of the sashes, at the edge of its knot, they attached a seal that had his, Dharmodgata’s, own name on it, and that’s what ‘sealing with the seven levels of seals’ means.

གནད་ཀྱི་ཟླ་འོད་ལས། ཆིངས་མ་བདུན་གྱི་མདུད་པ་བདུན་ལ་རང་གི་མིང་གི་རྒྱ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་རྒྱས་བཏབ་པའོ། །ཞེས་འབྱུང་ངོ་། །དེ་ནི་གླེགས་བམ་རྣམས་སྐུ་རགས་བདུན་བདུན་གྱིས་བཅིངས་ནས། སྐུ་རགས་རེའི་་་མདུད་མཚམས་ལ་ཆོས་་འཕགས་རང་མིང་གི་མཚན་མ་ཡོད་པའི་རྒྱ་རེ་བཏབ་པས་ན་རྒྱ་རིམ་པ་བདུན་གྱི་རྒྱས་བཏབ་པ་ཞེས་པ་ཡིན་ནོ། །

+ + + + + + +

In the visionary world of Revelations, God the Father holds the scroll — He is purposefully left out of depictions like the ones you see below, and it may be the square platform Solomon stood on when the Temple was consecrated that you are meant to see here, although it is indeed at the same time treated as a throne — and it is the Lamb that opens the seven seals one by one, improbable as that may seem, given that lamb's hooves are not well equipped for such tasks.

|

| “Empty throne,” marked by cross and lamb, enshrining the scroll with seven seals surrounded by seven lamp stands: Church of SS. Cosmas and Damian, Rome (526-530 CE) |

For a much more recent artistic version of the same, have a look at the altar and apse of the Augusta Victoria Church of Jerusalem:

|

| Altar and apse of the Augusta Victoria Church, Jerusalem |

|

| Detail from the altar of the Augusta Victoria Church, Jerusalem |

Addon June 15, 2022

I was just thinking that there are only two of the several sets of Seven Seals in which each individual seal has a given name. One is the set of the Tibetan Zhijé school.* The Judaeo-Islamic “Solomonic magic”** side I haven’t adequately discussed, I know, but the other is the Jewish set that sometimes has named members. It’s interesting to know, as Graham's major essay on the subject (“A Comparison of the Seven Seals in Islamic Esotericism and Jewish Kabbalah”) shows, that the Jewish set is based in an early piece of Hekhalot literature called Shīʿūr Qōmah. This very odd and quite controversial text dares to give dimensions to the macrocosmic figure of the godhead, and its description of the five fingers of a hand and the two eyes of that figure were eventually used in naming the Seven Seals. Although the Islamic versions don’t have these names, they do share with the Judaic what looks like the shape of a ladder in the middle, while the other symbols do often suggest (or are even explicitly identified with) vision/blindness or (various numbers of) fingers.

Observe that much of both the content and the context of the Islamo-Judaic seals is not findable in the Tibetan. You find no symbolic figures or ‘signs’ in the set of Seven Seals in Tibet. You find none of the symbolic correspondences with the seven then-recognized planets, or the seven days of the week. Perhaps most significantly of all, you never see the amuletic theme of personal protection in those same Tibetan accounts.

*(I know I’ve left off a bit of traditional Zhijé commentary that exists on this subject, perhaps another time. **By “Solomonic” magic I intend to use a single word for strains of ritual magic in Jewish and Islamic worlds that connect to the cultural image of Solomon as known in traditions that started with Josephus but in later centuries blossomed into an extensive body of lore. Many of the origins accounts of these texts and practices explicitly name Solomon as their source or conduit. This lore embraces the idea of King Solomon as ruler over not only the humans, but the animals and spirits as well, as if he had more than one kingdom under his royal command. Some personal items of his, but particularly his signet ring, could be used to express his sovereignty in magical contexts. I know this sketch is drastically spare and imprecise, but at the same time I realize some readers in the Tibeto-logical world may require a little background.