The white beard always gives me away, so no need to confess my age. But I will tell you it was back in 1989 that I first knew of the history book connected with the name Khepa Deyu (མཁས་པ་ལྡེའུ་). At the time I was in Nepal and got the opportunity to study some parts of the text, specific parts that interested me, indirectly with Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche.

The first part I chose to read was a challenging one, the Fable of the Owl and the Otter, meant to explain why the kheng-log, or revolts of the civilian workers, came about.

I also worked on the story of the final end of monasticism at the very end of the text. I suppose I was attracted by the apocalyptic tone of it. But with all the hype about the Y2K virus the end of the 2nd millennium did not bring the end of the world with it, and here we are, still going to conferences in Prague two decades later, under threat of a less virtual virus.

Jump ahead 20 years from initial exposure in 1989 to 2009, when I was commissioned by Thubten Jinpa to translate the entire 400-page book for the Library of Tibetan Classics. A three-year project is what I signed up for, but twelve years on I was spending the better part of my time working on it. I received a lot of excellent help even if I won’t name any names right now. You can find those names listed in the acknowledgements when the book is released on the 19th of this month.

To begin with I would like to say some words about the confusing issue of authorship. It is a question of identifying the sectarian entanglements of the three authors that best fits the theme of our panel,* so I will concentrate more on that.

(*The panel was called “Early Religious Networks: Monastic Institutions and Eclectic Traditions in the 11th–15th centuries.’’ This blog is a slightly modified version of the presentation to that panel.)

I’ll simplify by stating my conclusions about the identities of three different authors of three distinct historical works. I think some people will be surprised at this news, but in the end I believe there was only one Deyu we need to be concerned about, not two and not three. The one and only Deyu, according to me, is the author of the verse history. This verse history is quoted in both of the published histories we have, the one supposed to be by one Deyu José (ལྡེའུ་ཇོ་སྲས་) that I call “the small Deyu,” and the other longer, and I would say later, one so often attributed to a Khepa Deyu, “the long Deyu”). The two authors, whatever their real names might be, each semi-independently took the verses as their root texts, and composed or compiled their histories after the common pattern of a root text and commentary (རྩ་འགྲེལ་). The text by Deyu (ལྡེའུ་) is the root text for both works, and that is why they both have his name in their titles.

The authorship of the small Deyu is admittedly problematic. He is identified largely based on interpreting a difficult prostration verse in the long Deyu. The long Deyu's author is and probably will remain anonymous even if there are a couple of candidates that show some small promise.

|

| Various forms of the name of the root verse writer Deyu |

After a lot of detective work, I could find out the fuller name of the verse-writing Deyu as well as a disappointingly brief biography (located in Bhutan thanks to Karma Phuntsho's Endangered Archives Project grant). The fuller name and the brief biography are the two small things I could add to the sketch given by Chabpel in his preface to the 1987 publication of the long Deyu.

The fuller forms of the name of the verse writer you see here could only be uncovered by comparing a number of lineage lists.

To simplify, the verses by Deyu must date to the main period of his known activity. That means in decades surrounding 1180.

Deyu belonged to one of the several lineages that descended from Padampa Sangye. You can see Padampa here in what is probably his most famous portrait now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It in fact shows him in a form that pertains to the Zhijé school and not to the Gcod or ‘Cutting’ school although those Cutting images with their rattle drums and thigh trumpets are much more commonly seen.

The Zhijé lineages are divided among “Three Transmissions.” They are defined by Padampa’s three different sojourns in Tibet. It was one of the lineages of the Middle Transmissions that took place in Central Tibet during a more-or-less 10-year sojourn in Tibet, let’s say around 1060 or 1070 or so. And among the 6 transmissions that resulted from his teachings in those years, our verse maker belonged to the So tradition, the one with the golden star next to it. I’ve marked with a blue star the (today) much better known tradition of Kunga in the Later Transmission. Kunga’s is the one that continued to grow and form institutions during the next few centuries, and we are much better equipped with information about it.

The Middle Transmissions are not only a lot more obscure and exclusive to begin with, they were more or less absorbed in the coming 2 or 3 generations under the influence of the Nyingma-leaning Zhijé figure Tenné and three of his disciples named the Rog brothers. Because they were absorbed, they lacked the institutions that could transmit, preserve and elaborate on their historical accounts.

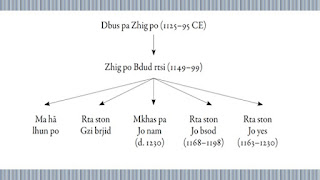

Even if it is scarcely visible in the texts themselves, as they are quite ecumenical and pan-sectarian in their scope, it is likely all three authors had lineage connections with both Nyingma and Zhijé. My hunch is they shared one and only one lineage, even if it might have been a composite lineage. The following chart

shows the relevant spiritual lineage of the Aro Dzogchen lineage that descended from that interesting figure Aro, subject of the dissertation by Serena Biondo that was much help to me in sorting this out.

There are two books that also helped me a lot:

One is José Cabezón's translation of the philosophical history by Rogban that dates to the early decades of the 13th century. It deserves a lot of attention from our panel, and it has very close affinities with the long Deyu. It shares the same Nyingma-Zhijé affiliations, so the many parallels shouldn’t surprise us.

David Pritzker’s Oxford DPhil, is on an earlier history This untitled anonymous work from the mid-to-late-12th century is more relevant for parallels with the long Deyu when it comes to Tibet’s imperial history.

To end with, and to keep things fast and sweet, as we must, I will highlight two passages from the long Deyu. Both of them can be located in Brandon Dotson’s dissertation with both text and translation. Both are describing the martial exploits of fighters conscripted in a particular region who went on to conquer yet another region. Let me tell you what I see in them, try to support it a little, and then find out if you can see it, too.

|

རྒྱའི་སོ་མཁར་བྱང་གི་བར་ལ་རྟ་པ་དགུ་སྒྲིལ་རྒྱུག་ཏུ་བཏུབ་པའི་ནང་ན། མི་སྤེ་ཐུང་ཙམ་པས་དགྲ་སྟའི་ཁ་ཁྲུ་རེ་ཙམ་ཐོགས་ནས། འཐབ་པའི་ཚེ།

The first highlight which I have lit-er-al-ly highlighted in yellow (you can see the actual page number above) evokes two things in my mind. It's northward of China and concerns border posts. This already sounds like the Great Wall of China. And the mention of how many horsemen can ride side-by-side makes us think of modern day tourist brochures that often mention how many horses or men could race side by side on top of it.

Secondly, I see in the short people with their large battle axes an image of the short fighting men known in ancient Greek culture even before Homer, the battle between the pygmies and the cranes.

|

| Nilotic scene from Sepphoris |

This image is commonplace, so well-known in Greek art and literary history that it has a one-word name: ‘Geranomachy.’ Google that.

And if we look for intersections between small humans and the great wall, there is another odd incident of it known from early Chinese sources. At least I know of one source dated 1574 about thousands of tiny corpses housed in 12 & 1/2" coffins that were found during a repair of the Great Wall.* I doubt its relevance, but today practically everyone in the Anglophone world at least believes that workers who died during the building of the Great Wall were buried inside of it. On the other hand: There are said to be plenty of other references to ‘small people’ in Chinese sources before and since, but I will leave it with this for now.

(*Qiong Zhang, Making the New World Their Own, pp. 69-74, & esp. p. 73.)

And if we need more proof, the Chinese Fort Lom-shi mentioned here might stand for Chinese Longshan, or ‘Dragon Mountain,’ and therefore likely the Panlongshan, or ‘Coiling Dragon Mountain,’ today’s name of a section of the Great Wall located 160 kms. northeast of Beijing. Well, I don’t want to get lost in geographical problems and I will defer to experts who could better deny or verify this.

The oddity of this is that I know of no other reference, in any classical Tibetan text, to the Great Wall of China. I imagine someone could enlighten us on this point.

གྲུ་གུ་གསེར་མིག་ཅན་གྱི་ཆུང་མ་ཧོར་མོ་སྤིར་མདུང་ཅན། ནུ་མ་གཡས་པ་མེ་བཙས་བསྲེགས་ནས། མདའ་སྤར་གསུམ་གྱི་མགོ་ཙམ་པ། རྡོ་ཁེབ་ལའང་ཅུར་འབྱིན་(154ན)པ་ལ་་་

The second passage I’ve highlighted is about Turkish, perhaps Uighur women who hold shields and spears. Obviously that means they are women soldiers. But we know they are not just any women soldiers, but specifically Amazons, when we read how they burned off their right nipples. It doesn’t seem to be the case that the breast, let alone a small part of it, would in fact impede the use of arrows and spears. The name “Amazon” itself probably comes from a local Scythian term with another meaning, but the Greeks found their own Greek etymology meaning ‘absent breast’ and then created the story to explain it. The breast burning detail in the Tibetan text demonstrates to us beyond doubt that the influence of the Greeks lies in its background.*

(*All these points have chapters devoted to them in Adrienne Mayer’s 2014 book, The Amazons. About use of magnets in arrowhead extraction, there is a reference to be found in the Rgyud Bzhi medical scripture [Barry Clark’s tr., p. 134] and Suśruta also mentions it as one of 15 extraction methods [Gabriel’s book, p. 132]. I haven’t learned that Amazons knew of this in sources I know of.)

|

| A Tibetan “Amazon” advancing under fire |

I suggest that the allusion to the Pygmies, if that is what it is, and the account of the Amazons, which is no doubt there, are both filling a particular task in the context we find them in.

As I said, Brandon Dotson's dissertation covers the entire catalog of law and administration, including this section on the three main military divisions where we find these accounts. If we look in the most general way into the internal structure of each of the three entries we find that each one may be sub-divided into three sub-sections: 1. The 1st sub-section defines geographical limits of the area from which the soldiers were conscripted. 2. The people they encountered in their foreign excursions. 3. A description of the soldiers and just how heroic and self-sacrificing they were.

Tibet's imperial armies are portrayed as penetrating as far off as they can imaginably go,* and there, in that far distant place, they meet the remarkably small fighting men and the women warriors. These connect to Eurasian lore about Pygmies and Amazons. It’s as if when and if one could go far enough, one might encounter such unusual humans. I’d contend if I had the time that, in the Tibetan accounts, the pygmies and Amazons are continuing the same tasks they had performed for the Greeks long before them: the Pygmies beyond the far side of Egypt, and the Amazons far north beyond the Black Sea in Scythia, or present-day Ukraine. They are the far outlying peoples with special characteristics the soldiers reported about when and if they got back home. In these instances, the incursion of very foreign ideas about Pygmy men and Amazon women is a result of military excursions, or at least appears in accounts of military excursions. The literary incursions of Greek elements, whatever route may have brought them from Greece to Tibet, were found useful in this Tibetan account of military excursions.

(*The histories sometimes say that 2/3rds of the world was conquered during the reign of Emperor Relpachan.)

Franz Kafka's short story called “The Great Wall of China”* is one of his more interesting literary works if you ask me, perhaps the only one where Tibet receives any mention (well, except for one paragraph in his letters to Milena). This story is no more about the Great Wall of China than his Metamorphosis is about waking up as a giant insect. True enough, both stories are about confinement, confinement on various scales, whether voluntary confinement or involuntary containment. Let me quote a few excerpts from it:

"Against whom was the great wall to provide protection? Against the people of the north. I come from south-east China. No northern people can threaten us there. We read about them in the books of the ancients...

“... When children are naughty, we hold up these pictures in front of them, and they immediately burst into tears and run into our arms. But we know nothing else about these northern lands. We have never seen them, and if we remain in our village, we never will see them, even if they charge straight at us and hunt us on their wild horses. The land is so huge, it would not permit them to reach us, and they would lose themselves in empty air.”

(*Tr. by Ian Johnston, Kartindo Publishing House, print on demand, p. 13.)

In a very different context, and from Kafka’s mouth, not his pen... In an interview he tells the interviewer that his school was here, his university over here, and his office over there. He adds:

“My whole life is confined to this small circle.”

As he said so he traced small circles with his finger in the air.

° ° °

Note: This is a blog version of a Powerpoint presentation at the IATS seminar held in Prague in July 2022. Each participant was limited to 15 minutes, so it was a little hurried, and if it sort of sounds like a talk, it’s because it is. In the course of the conference, Kafka’s birthday took place, but I didn't see any signs of celebration. More attention was paid to which of us had the latest positive test for Covid. So if you were thinking it may be too early to make up for missed conferences, you may very well be right. I shudder to think the press will pick up on a new strain named in honor of the event. The IATS-2022?

PS: Just today, July 14, I found a strong line below the T and understood that I myself could not escape taking up my part in the pandemic. Very few of the participants dodged this bullet, and then only because they had recently recovered. Premonitions were entirely justified, it was a superspreader event.

Most recommended readings and references

Barry Clark, tr., The Quintessence Tantras of Tibetan Medicine, Snow Lion (Ithaca 1995).

Brandon Dotson, Administration and Law in the Tibetan Empire: The Section on Law and State, and its Old Tibetan Antecedents, Doctoral dissertation, Oxford University (2006).

Richard A. Gabriel, Man and Wound in the Ancient World: A History of Military Medicine from Sumer to the Fall of Constantinople, Potomac Books (Washington D.C. 2012).

Adrienne Mayor, The Amazons: Lives & Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World, Princeton University Press (2014). If you want something reliable and reliably interesting about Amazons, this is at the top of my list, in fact the only book on the subject I found time to read all the way through.

Asher Obadiah and Sonia Mucznik, “Myth and Reality in the Battle between the Pygmies and the Cranes in the Greek and Roman Worlds,” Gerión: Revista de Historia Antigua, vol. 35, no. 1 (2017), pp. 151-166. “According to some scholars, this folktale... was conveyed to the Greeks through Egyptian Sources.” Far from battling the very short people, the foreigners/Greeks instead feel pity and advise them on how to better defeat the cranes.

Alex Scobie, “The Battle of the Pygmies and the Cranes in Chinese, Arab, and North American Indian Sources,” Folklore, vol. 86, no. 2 (Summer 1975), pp. 122-132.

Qiong Zhang, Making the New World Their Own: Chinese Encounters with Jesuit Science in the Age of Discovery, Brill (Leiden 2015).