|

| Zhang Yudragpa: Detail of a tapestry portrait |

Today’s

small blog effort, I feel it is fair to warn you, is likely to be of limited

interest to all but the most dyed-in-the-wool Tibeto-logical specialists. Even then, I don’t have a whole lot of

time to sit and chat. There are so many things on my plate, I hope you’ll

excuse me if I excuse myself so I can dig in, or should I say bite the bullet, in the hope of completing one or another of my

several assignments, at least. Don’t even say the word ‘deadline’ within

earshot if you know what’s good for you. I’m not in the mood to hear it. I

suppose you might even get a particularly nasty reaction if you’re not careful.

Be forewarned.

Enough

of these idle threats with nothing to back them up. If you find yourself

curious to find out a little bit about the man this fuss is all about, look at

Lama Zhang's biography in Treasury of Lives. For now I’m just going to list some outstanding new works about Zhang

Rinpoche* and his Works that have

appeared since the turn of the millennium. Then I will announce the first

public release of a bibliographical survey of his Works that I’ve been working on for quite some time now.

I’m thinking a couple of you will find it of interest, and among those, one or

two will find it useful for some good purpose or another. Those numbers sound

more than adequate to me.

(*The full and usual form of the name of the initiator of the lineage of the Tselpa Kagyü [Tshal-pa Bka'-brgyud] is properly spelled using the Wylie system as Zhang G.yu-brag-pa Brtson-’grus-grags-pa [1123-1193 CE], and as far as I’m concerned that’s the name that he ought to be remembered by in history, although you may prefer a phoneticized version, like Zhang Yudragpa Tsondrüdragpa or the like. There are hundreds of variations on his name, many of them of his own making. Still, if we want to keep things short and simple, I see no reason why we shouldn’t speak of him as either Lama Zhang or Zhang Rinpoche, do you?)

Here is the list —

1. Karl-Heinz Everding, Der Gung thang dkar

chag: Die Geschichte des tibetischen Herrschergeschlechtes von Tshal Gung thang

und der Tshal pa bKa’ brgyud pa-Schule, VGH Wissenschaftsverlag (Bonn 2000). This publication

contains Romanization and German translation of a Tibetan Guidebook on the history and holy objects

contained in the monastery of Tsel Gungtang that was composed by the

Dge-lugs-pa author ’Jog-ri-ba Ngag-dbang-bstan-’dzin-’phrin-las-rnam-rgyal (b.

1748) in the year 1782 at a time when Gung-thang was under the administration

of Sera Monastery. To read a little more about this publication, press here.

2. Per K. Sørensen & Guntram Hazod, in cooperation

with Tsering Gyalpo, Rulers on the Celestial Plain: Ecclesiastic and Secular

Hegemony in Medieval Tibet, a Study of Tshal Gung-thang, Verlag der Österreichischen

Akademie der Wissenschaften (Vienna 2007), in 2 volumes with 1011 pages! This

contains an English translation of the same Guidebook by ’Jog-ri, but in addition to

that it contains such a wealth of information in its introduction and multiple

appendices — not to mention the many maps and great color photographs — that it

may take Tibetology many decades to begin to absorb it all, let alone catch up. For a review by Bryan Cuevas, look here.

3. Carl S. Yamamoto, Vision and Violence: Lama

Zhang and the Dialectics of Political Authority and Religious Charisma in

Twelfth-Century Central Tibet, doctoral dissertation, Department of Religious Studies,

University of Virginia (May 2009). Although a work of high academic standards,

it will certainly be published as a book very soon, and when it is I imagine

many will find it to be the most accessible book yet on the subject of Zhang

Rinpoche. For an abstract, look here.

|

| The newest book on Lama Zhang |

4. Gra-bzhi Mig-dmar-tshe-ring (b. 1983), Tshal

Gung-thang Gtsug-lag-khang-gi Dkar-chag Skyid-chu'i Rang-mdangs, Bod-ljongs Mi-dmangs Dpe-skrun-khang (Lhasa 2011), in

383 pages. I suppose the title could be translated “The Kyichu River's Inherent Glow: Guide to the Temple of Tsel

Gungtang,” although it is much much more than a guidebook, with so much

information about the temple and monastery during more than eight centuries of

its existence. It pleases me very much to know that someone in Tibet is interested in doing

this work. It has some small color illustrations and among these perhaps the

most worthy of notice are the before-and-after photos of Zhang Rinpoche's

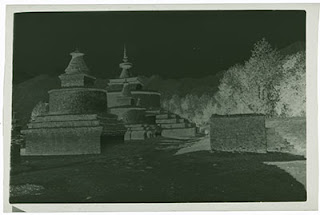

funerary chorten, now reduced to a pile of rubble. You can see it in the following old photo; it's the larger chorten on your right. Lama Zhang had just finished building its lower steps when he died in 1193.

|

| Tsel Gungtang, negative of photo by Hugh Richardson |

So,

I would like to suggest that those who want to go to the web version of the

catalog of Zhang Rinpoche’s works, try going here. Or if you are

impatient and want to immediately download the complete catalog in a Word file, all you need to do is click the link just given, which ought to transport you to Dropbox (I hope someone will

let me know if this works OK, since it’s my first experiment with this mode of

file distribution; the file is supposed to truly exist there, even now, in

something that takes the form of a cloud, ready to be precipitated down onto

your personal machinery). The download should be quick. It's only about 265 pages long. I wanted to put up the Gung-thang Dkar-chag, but haven’t succeeded yet.* For now, I’ll just say:

Good luck and gods’ speed, until we find the time to blog again.

(*Oh, wait a minute. Try here.)

|

| A modern (or restored?) representation of Lama Zhang, Tsel Gungtang Monastery |

~ ~ ~

The frontispiece is from a very old fabric artwork that was preserved in the Potala Palace and is apparently now in the museum near the Norbu Lingka in Lhasa. It has an inscription on the back that has been and will be the subject of much discussion, but it does identify the main subject (“Dpal-ldan G.yu-brag-pa”), leaving no doubt that it is meant to represent Lama Zhang. This artwork may date from around the 15th century, but at the same time it may be a very faithful copy of an earlier artwork (perhaps a painting) dating much closer to the time of Lama Zhang. The details remain to be worked out. It has by now been published a number of times, but perhaps best is Bod-kyi Thang-ga at p. 62 (the catalog entry in this book says it was woven in the time of the late Sung).

Yes, there is a heaven. If you are the sort of person who derives enjoyment from looking at listings of Wylie-transcribed Tibetan titles in Gsung-'bum-s and Bka'-'bum-s, you can find quite a few of them here. If you are that sort of person, you are my sort of person.

And one more thing. If you’d like to read an English translation of what may very well be Zhang Rinpoche’s most famous literary work, try to get to the download HERE. I've also put up a never-before published Tibetan script edition of the original work. If the link isn’t working, you can complain. Please do.

Yes, there is a heaven. If you are the sort of person who derives enjoyment from looking at listings of Wylie-transcribed Tibetan titles in Gsung-'bum-s and Bka'-'bum-s, you can find quite a few of them here. If you are that sort of person, you are my sort of person.

- - -

And one more thing. If you’d like to read an English translation of what may very well be Zhang Rinpoche’s most famous literary work, try to get to the download HERE. I've also put up a never-before published Tibetan script edition of the original work. If the link isn’t working, you can complain. Please do.

- - -

Postscript (February 11, 2013): If you would like to hear Carl Yamamoto talk about his book that was meanwhile published, there is an hour-long interview in the form of a Podcast (available through iTunes) in the series “New Books in Buddhist Studies.” I haven’t found a way to make a direct link, but you ought to be able to locate it with an internet search. (Perhaps you will have to sign up with iTunes, but before going to that extreme try this link.)

PPS (February 13, 2025): I just noticed this title on Lama Zhang in a book catalog, Ye-shes-zla-ba, Tshal-pa Bka'-brgyud Srol-gtod-mkhan Zhang Brtson-'grus-grags-pa dang 'Brel-ba'i Lo-rgyus Zhib-'jug, Bod-ljongs Bod-yig Dpe-rnying Dpe-skrun-khang (Beijing 2024).

NOTE to myself: Links updated February 2025.