I’d like to start with a story. Not one about myself, one told by David Snellgrove about his 1956 travels in Dolpo, Nepal, in his book Himalayan Pilgrimage. Bear in mind, this was back when Nepal as a whole was just opening up to foreign visitors, but even then very few were able to travel to areas this remote.

I’d recommend reading the whole chapter, right now I will restrict myself to his description of a day at the Bön monastery of Samling. At the time the monastery only had a dozen houses and two permanent residents, one of them being the abbot’s.

When rituals were held laypeople would come to join in, not just as audience, but as active participants. Snellgrove had already offered the abbot some eyedrops for his sore eyes, and meanwhile they had gotten better, so the abbot was at least trusting and appreciative. To be sure, the abbot was impressed when Snellgrove demonstrated an ability to read Tibetan letters. He even called him a “Bon Tulku.” Perhaps it was an extraordinary compliment, perhaps a little tongue-in-cheek, we’ll never know.

Here are some portions of his narrative. I have skipped through it to underline particular parts.

Himalayan Pilgrimage, p. 119:

“We started with the ‘Mother’ (yum) in sixteen massive volumes. The pages with their gilt and silver letters on a black ground measured about 2 & a half feet long by 6 inches wide. There were three hundred or more pages in each volume, all wrapped in cloths and bound between carved half-inch boards. There was dust everywhere. This work is properly known as the ‘Great Sphere’ (khams chen) and corresponds to ‘Perfection of Wisdom’ section of the Tibetan Buddhist Canon, which is also nick-named ‘Mother’.”

... ... …

“Revered as the formal expression of absolute wisdom, they are read as a rite to give immediacy to wisdom’s innate power. Certainly the reading on this occasion was a perfunctory affair. Everyone present opened one of the volumes, flicked the dust out of the pages and began to read sonorously.”

... “The ‘Mother’ revealed itself as a complete imitation of its Buddhist equivalent.”

The next pages have many more statements like this, about how this and that scripture is ‘obviously’ just an imitation of Buddhist scriptures.

At pp. 122-23:

“The day’s performance had fully served its purpose, for I now had a general idea of the contents of the collection and knew which books were worth looking at again.”

Saying so isn’t very helpful to the ideas I’m searching for, but I think today we naturally object to the rhetoric of “fully served its purpose,” since it’s so clearly not the purpose of the text reading to satisfy the research aims of foreigners, a kind of spywork. We’re likely to think of the controversies surrounding Fritz Staal’s Agni (he revived an extremely elaborate and costly Vedic ritual entirely in order to study it), but anyway... all this leads off into a different direction than I intended.

However that may be, I say: Give him a break. He did mention “Wisdom’s innate power,” and that couldn’t be more on the mark. Recall how L. Austin Waddell once purchased a small monastery and made sure it was filled by monks just so he could study what they would do there. Was anyone harmed by this arrangement? It’s good to ask questions, but my questions lead off in a different direction.

This ritual observance — the same one Snellgrove made into his ethnographic object only to make light of it (we have to wonder, Was he consciously pandering to an imagined audience?) — is arguably a practice going back to the beginnings of Buddhism two and half millennia before present. And I suggest it may prove worthwhile to refocus our attention on this practice before passing judgements about how the Bön similarities and distinctions may have come about.

I’d like to mention an article by Franz-Karl Ehrhard on “reading authorizations” (ལུང་) because, on its page 209, there are examples of some intriguing ways of shortening lengthy readings, methods bearing names like “cutting off the wave.” Some apparently read only the beginning, middle and end of each page. I just want to say that such shortcuts are well enough known to get names of their own.

Inviting nuns and monks into your home for ritual readings has been a continuous practice in Tibetan Buddhism for at least the last millennium. Some famous early figures were known practitioners: such as Machik Labdron who as a young woman served as scripture reader/reciter in laypeople’s homes. And it continues today, as one might gather from jokes I heard in Bodhanath in Nepal in the late 1980’s.

Here are two examples where a householder asks a question of one of the monk reciters:

Q: In the past whenever we invited the monks to our house to read the Perfection of Wisdom, we always heard the name of Rabjor repeated many, many times. Why haven’t we heard it today?

A: Wait! Here they are coming up right now, "Rabjor, Rabjor, Rabjor, Rabjor."

Another example:

Q: Why is it I see you move your head to the right only three times when you are reading!

A: We don’t go back empty!

So, we can see that not only Snellgrove, but Tibetans themselves could make light of the practice, but in a way that might actually serve to tell us how significant it is. To understand the jokes and find them funny, at least, requires familiarity with the practice. And, more to the point: These ritual readers have a long line of predecessors that plunges us far back into the history of Buddhist scriptures, back to the first centuries before they were even written down.

One book that impressed me so much in my early days that I still remember it well is a certain science fiction book. It moves in a different direction, but still I think it helps us think seriously about changing strategies in text preservation that might take place when the ‘text’ transitions into manuscript form.

Ray Bradbury’s famous novel is exactly as old as I am, but it is set in the distant future, in the 24th century. The main character Guy Montag works as a fireman, but this future kind of fireman doesn’t put out fires, since all houses had been built with foolproof fireproofing. Instead he is called to incinerate books wherever they may be found.

I would like to insert a little commentary: Bradbury wrote at exactly the time when televisions were first being installed in a large number of homes, and people voiced fears that the audio-visual media would be used for information control placed in the service of social control, but also that silly and pointless entertainment would take the place of moral edification and learning.

So, going back to the novel: In the 24th century people have large flatscreen televisions that are oddly interactive, drawing the viewers into the narrative. I recommend reading the book if you haven’t, especially for the way it ends, which I must spoil for you: Guy Montag, pursued as a criminal book owner, crosses over the river away from his familiar dystopian society, and joins a band of outcastes in the woods. Each of them embodies a particular book in their memory. In order to ensure its preservation, each one recites it to themselves, but also into the ears of an apprentice who memorizes it in order to pass it on to the next generation.

I’ve long thought that Bradbury was influenced by the Dharma Bhāṇaka who played such a leading role in Buddhism’s lengthy orality phase. I can’t tell you where he might have read or heard about it, but I believe he did.

Buddhism’s original orality has been nicely explored and explained in an essay by Peter Skilling I recommend as a short and pithy summary with up-to-date information and plenty of bibliography.

The latest manuscriptology tells us that the earliest written examples of Buddha Word date from not too long — maybe a century, maybe two? two and a half? — before the time of King Kanishka. His dates have long been a problem, but it seems he reigned in the first half of the 2nd century CE.

Kanishka is credited with sponsoring the “third rehearsal.” Before I go ahead and read a passage about it from the long Deyu history dating to around 1261, I’d like to say a few things. The usual translation of saṅgīti is not “rehearsal” but “council.” This word council creates the false expectation that the reasons for holding them are the same as the councils of early Christianity, to decide which written books will be canonical and/or to confront unsettled doctrinal questions. It has to be emphasized that the more accurate translation of saṅgīti would be “communal recitation,” or even “chorus,” since the main aim of this meeting was not really to discuss differences even if that did occur in some infamous instances, so much as to ensure communal harmony in the monastic Community as well as to see if they were on the same page, so to speak. On these important points, see Bhikkhu Anālayo’s essay “First Saṅgīti and Theravāda Monasticism” and his book published last year. (The book details are listed below.)

The following is from A History of Buddhism in India and Tibet: An Expanded Version of the Dharma’s Origins Made by the Learned Scholar Deyu, p. 317, in its account of the Third Council:

[King Kaniṣka] was not only intelligent and wise but he was also one with great faith who believed in the Dharma teachings. He investigated to find out if the Dharma teachings of the Buddha, the Word, had suffered interpolations or not. What he found was that they had decayed compared with their previous condition. Even after the compilation was done, there were some ordinary unenlightened people — people not favored with the dhāraṇi of never forgetting — who recited scripture with gaps and additions. That is why, at that time, they did what was necessary for making the Teachings of the Buddha remain for a long time and benefit sentient beings of the future. They committed the Baskets of the Word to texts with words written in letters. They inscribed them in palm-leaf bundles and sacred Volumes. There turned out to be five hundred incense-elephant loads worth of them, and after consecration, they were placed in the temple.

I want to emphasize, these meetings were supposed to ensure the continuity of the teachings through recitation and memorization. Communal recitations were an opportunity to check for accuracy. They served purposes that might in book culture be filled by editors or editorial boards.

I made myself a very long reading list at the beginning of the year, but unfortunately there was so much to read in English, not to mention Tibetan, that I didn’t get nearly as far as I had hoped. High in the list were works by Mark Allon and Eviatar Shulman, but I most recommend the recent book by Bhikkhu Anālayo, which I found quite interesting for its way of dealing with textual change during the era of orality. Still, my own area for exploration is first of all in the Mahāyāna, not the Theravāda, and secondly, mostly long post-dating the orality-only era.

I most recommend some recent Oxford Zoominars, all available for free viewing on the web:

Natalie Gummer, “The Dharmabhāṇaka’s Body and the Ontologization of Authority,” February 21, 2022, 6:00 pm.

Robert Mayer, “Dharmabhāṇakas, Siddhas, Avatārakasiddhas, and gTer stons,” May 23, 2022, 6:00 pm.

Ryan Overbey, “Theorizing Buddhist Revelation in the Great Lamp of the Dharma Dhāraṇī Scripture,” February 6, 2023, 5:00 pm.

I’d like to especially draw attention to the third one by Ryan Overbey, concerning The Great Lamp of the Dharma Dhāraṇī Scripture, a lengthy text available only in an end-of-sixth-century Chinese translation. It purports to transform the wielder of its dhāraṇī into a perfect Buddhist reciter / preacher: a Dharmabhāṇaka. Becoming a perfect Reciter entails entering “the Treasury of Tathāgatas,” a state in which the Reciter accesses the awakening of Buddhas. Ritually re-presencing the Buddha in the body of the Reciter, the Reciter’s sermons are authorized as the Word of the Buddha. Overbey says the Dharmabhāṇaka is the key figure in representing the Buddha in this text. And the text describes a kind of secret letter-code in 40 or 42 letters divided into three classes, the classes of vowels, consonants and nasals. The number of 42 letters suggests it would be identical to the Arapacana alphabet, the alphabet of Kharoṣṭhī script, and this shouldn’t be surprising in the least, since the translation of this text into Chinese is attributed to a Gandhāran monk.*

(*If this sentence made no sense, read the introductory chapters to Salomon’s book. Thanks to Jonathan Silk for recommending a more cautious way to phrase this, with reference to the database of Michael Radich. There’s a whole chapter in Overbey's dissertation I’ll have to read before deciding for myself if the caution is justifiable or not.)

Similar ideas about envisioning the Dharmabhāṇaka as ritual stand-in for the Buddha himself may be encountered in the Zoominar of Natalie Gummer as well as in some of her recently published articles. Gummer’s studies are based in a few of the better-known Mahāyāna Sūtras, the Suvarṇaprabhāsottama and Saddharmapuṇḍarīka.

I should also mention here a 2011 article by David Drewes. Drewes surveys a large number of Mahāyāna Sūtras, and in doing so helps us visualize the social scene involved in the ritual in early centuries. Recitations were likely to take place on monthly fast days when laypeople were anyway most likely to visit the temples and monasteries. The Dharma Reciter, who could be a woman as we find made explicit here and there, would sit in an elevated place or even a throne, and the recitation itself could continue all through the night.

I find this colophon page very charming and illustrative at the same time. See how the frame with the devoted patron figures — their names are given — flows almost seamlessly (the horse artlessly steps out of one frame into another, as if it were unconscious of crossing over a huge time gap) from the narrative of Sadāprarudita’s quest for the perfect Dharmabhāṇaka to the sacred Volume of the Perfection of Wisdom, here depicted on a stand in front of the patron couple, the same patrons who sponsored the scribing of it. The more I look at it the more meaning it seems to emanate. But on a critical note we should observe that the final chapters of the scriptures with the story of Sadāprarudita (རྟག་ཏུ་ངུ་) are absent in earlier Chinese translations. These same chapters might even be lacking in the earliest Tibetan translation, a matter that will need to be sorted out over time when close study of those translations will be taken up in earnest.

In my dissertation of 1991 I looked into matters relevant to the Bön and Chö (བོན་ & ཆོས་) Wisdom Scriptures as one of several significant side issues in my pursuit of Shenchen Luga’s place in history. These issues included comparison of the 32 bodily signs of an Enlightened One, along with an initial exploration of stories about the earliest Prajñāpāramitā translations into Tibetan (look here).

I went into those earliest translations once more in a blog of 2012, “1,200-Year-Old Perfection of Wisdom Uncovered in Drepung” after learning of an amazing new find. It had by then become known that two volumes from a 9th-century scribed set containing a late 8th-century version of the Hundred Thousand had surfaced in Lhasa. An inscription added to the first page tells us it had earlier been rescued from a fire in the now-destroyed temple of Karchung [where there was once a pillar inscription of Emperor Senaleg — སད་ན་ལེགས་], across the Kyichu from Lhasa. Kawa Sherab Zangpo reported on these Volumes at Königswinter in 2006, with the article appearing in 2009. He had found the third volume in June of 2003, and the second volume in October of the same year. In May of 2011, Sam van Schaik reported in his blog that the persons named as scribes of those two surviving Volumes were in fact scribes of Chinese and Tibetan ethnicities known from Dunhuang scribal colophons. That clearly shows that the Lhasa Volumes had actually been scribed in a workshop in Dunhuang.

I just want to remind you of a set of Volume-related practices, normally ten of them, found in a number of Pāli and Mahāyāna sources. As these lists always includes ‘writing’ they are surely post-dating the oral-written watershed, somewhere in the centuries close to the beginning of the Common Era. Here we see that the Khams-brgyad (Eight Elements) of Bön has similar ideas. It may be obvious, but the first three would only be relevant to a literate book culture, while the last three would be just as relevant to oral as to literate recitation practices. I have to emphasize the recitation practices continued. Book culture didn’t stop it, just added elements to it, most obviously paper, pens/brushes and ink. Even memorization practices continued more-or-less as before. And I would argue that contemporary practices such as Wisdom Scripture readings and reading authorizations (lung) as well can only exist because of the orality phase that preceded written scriptures.

Khamgyé — Eight Elements — ཁམས་བརྒྱད།

1. The Element of Coming to Be — སྲིད་པའི་ཁམས།

2. The Element of Continual Flow — རྒྱུན་གྱི་ཁམས།

3. The Element of Appearance — སྣང་བའི་ཁམས།

4. Element of Empti[ness] — སྟོང་པའི་ཁམས།

5. The Element of Clarifying Particulars — སོ་སོ་གསལ་བའི་ཁམས།

6. The Element of Awareness — རིག་པའི་ཁམས།

7. The Element of the Full Sphere — དབྱིངས་ཀྱི་ཁམས།

8. The Element of Evenness [Full Knowledge] — མཉམ་པ་ཉིད་ཀྱི་ཁམས།

Here you see the Eight Elements that broadly characterize the ’Bum section of Bön scriptures as a whole. More specifically, it serves as the most general outline of the 16-volume version of the scripture that likely derived its own title from the list, the Khamgyé, or Eight Elements. Each of the Eight Elements is covered by two of the 16 volumes, in the order given here. Not so obvious is the fact that the Eight Elements occur in conceptually joined pairs, with the first of each pair tending toward the objective spheres and the second tending toward the inward or subjective spheres. There is a strong streak of rationality in it. And at the same time I’m convinced after a little database-searching that these Eight Elements, whether individually and as a group, are not shared with the Chos Wisdom Scriptures found in our modern Kanjurs. They are unique to the Bön Wisdom Scriptures. Yes, there is something special about this Bön transmission of Buddhist text and text-related practice. I’m convinced the more we look the more we will find. Starting as we too often do from the commonplace sectarian polemical positions on the subject — nefariously motivated text alteration — we would never think it worth our while to look further. Since, assuming we are not the type of person who would build castles on the hot air of sectarian arguments, the historical circumstances are entirely dark for us, our best method is to pursue lines of enquiry that could possibly shed some light. These small works listed below are a good place to start searching for those cracks in the wall that could conceivably let in a little light.

The three Khamgyé texts by Lhari Nyenpo are these:

A. Khams-brgyad-kyi Zhun-thig Rnam-dbye Grangs-su Bkod-pa. Thirteen topics.

B. Khams-brgyad-kyi Phyi-mo Gsum-la Btug-pa’i Dag-yig. On the three ‘grandmother’ texts or Vorlagen.

C. Khams-brgyad Gtan-la Phabs-pa’i Rnam-dbye Spyi-don Dgu-yis Bstan-pa. Nine topics.

That was just a list the titles of the three very brief extracanonical texts by Lhari Nyenpo (ལྷ་རི་གཉེན་པོ་) that often accompany the Eight Elements scripture in 16 vols., the one found by Shenchen Luga in 1017 CE.* We’ll look at the initially confusing set of author names in the colophons in a moment and then say something about their content. First I want to go into the identity and the biography of the author a little. I have to thank Jean-Luc Achard for locating the biography for me when I was unable to do it myself.

(*All three texts have been transcribed in an Appendix at the end of this blog. Among the several versions of the three texts I could find, there is even an eBook version placed on Scribd website that can be downloaded if you or a friend has a subscription. I have to thank Gendun Rabsal for providing the texts as found in the 1975 Indian publication as preserved in Indiana University Library, which is the one I prefer.)

The biography of Lhari Nyenpo is by one Dmyal-ston Lha-rtse, a direct disciple of his. It tells us Lhari Nyenpo was born in a Mouse year with no further specifications. His birth was predicted ahead of time by the famous Khro-tshang ’Brug-lha, known to Bönpos for his divination methods and for revealing the Chamma (བྱམས་མ་), or “Outer Mother Tantra” literature. His mother died when he was ten and his father sent him to study with the three main disciples of Shenchen Luga, the main representatives of the Southern Treasures (ལྷོ་གཏེར་), despite the fact that his ancestors had followed the Northern Treasures (བྱང་གཏེར་), not the Southern. He broke off his studies at one point to go to Tingri Langkhor, where he circumambulated the shrine for Padampa Sangyé. That he did so is less surprising when we remember that Khro-tshang ’Brug-lha was well known for his association with Padampa. But Lhari Nyenpo’s visit to his shrine must mean Padampa had died already when the former was a young man. This suggests a later date for Lhari Nyenpo, perhaps 60 years later, but then it appears Padampa’s own death date may need moving back by at least twelve years or so from the usual Blue Annals date of 1117 to 1105, so the chronological situation is muddier than we would like. This isn’t at all unusual for pre-Mongol-era figures who usually only made use of the twelve-year animal cycle for datings.

After several years of travel and study he returned to his home valley of Shang (ཤངས་) and to his father. At 23 years of age he married, but had no child before age 40. He became a teacher in his own right and much of the remainder of the 48-page biography is related to his students and teaching activities. All three of his teachers, belonging to the Spa, ’Bru and Zhu clans, attended his father’s funeral. This would have taken place when he was in his 30’s but before he turned 40, when his first son, the first of two, Khorlo Gyelpo (འཁོར་ལོ་རྒྱལ་པོ་) was born. Now the Spa teacher was born in 1014, the Zhu in 1002, and the ’Bru lived from 996-1054. In the case of ’Bru, the Horse year of his death as given in our biography does fit the year 1054, for what it’s worth.

Despite our hopes, no specific mention of the three small texts that interest us right now could be found in the biography. The only thing I could find is at p. 40, line 6: a mention of the Hundred Thousand as one of the many subjects about which he made commentaries and outlines. Unfortunately, I know of only one further work by him that survives today, a Bardo Prayer (try this link).

On the way to Ü, the central province, he stopped in Nyemo (སྙེ་མོ་) Valley where the local Bönpos awarded him a place called Zangri (བཟང་རི་). In effect he founded this significant monastery as we know from many other sources. He died in a Sheep year, in his 72nd year.

This information about the earliest manuscripts of the Eight Elements is from the second brief text by Lhari Nyenpo. As it says already in the title, it intends to compare the three direct copies from Shenchen’s treasure manuscript. I believe this would be the first Tibetan-authored text-critical study of any Wisdom Scripture manuscript. The treasure manuscript was copied by Chogla Yungdrungkyi (ཅོག་ལ་གཡུང་དྲུང་སྐྱིད་) who, after copying it offered a copy to Shenchen Luga that was called Hardened Leather Cover. The same person made a further copy for himself called Red Hundred Thousand. The Great Eight Elements in Tiny Black [Letters], scribed only with black ink was a ‘son copy’ on basis of the treasure manuscript that is preserved even today in Zhu Rizhing (ཞུ་རི་ཞིང་) Monastery. It makes use of this Tibetan word,

and this is the very word I want to concentrate on for the rest of the time: drekang (འགྲེས་རྐང་).* After many years of pondering I still don’t have a satisfying English translation for it. I’ve sometimes felt the urge to throw away all my dictionaries, useless things that they are when you need them the most. You may know the feeling. All the same, I do have ideas about what it means. It means the repeated statements you find in the Wisdom Scriptures, with each repetition inserting a different element from a long list of dharmas or böns both sangsaric and nirvanic. The list is, keeping its original order, collated one-at-a-time into empty slots in repeated portions of prose or verse. For convenience, until I find a more appropriate term, I’ll just call them ‘repetition statements.’ Conze recognized this phenomenon and described it long ago in his 1978 book entitled Prajnaparamita Sutras, p. 10:

“These three texts [the 18,000, 25,000 and 100,000 Prajnaparamita Sutras] are really one and the same book. They only differ in the extent to which the "repetitions" are copied out. A great deal of traditional Buddhist meditation is a kind of repetitive drill, which applies certain laws or principles to a certain number of fixed categories. If, for instance, you take the statement that "X is emptiness and the very emptiness is X", then the version in 100,000 lines laboriously applies this principle to about 200 items, beginning with form, and ending with the dharmas, or attributes, which are characteristic of a Buddha. Four-fifths of the Satasahasrika, or at least 85,000 of its 100,000 lines, are made up by the repetition of formulas, which sometimes (as in ch. 13 and 26) fill hundreds of consecutive leaves. An English translation of the Large Prajñaparamita, minus the repetitions, forms a handy volume of about 600 printed pages (see p. 37). The reader of the Sanskrit or Tibetan version must, however, struggle through masses and masses of monotonous repetitions which interrupt and obscure the trend of the argument.”

(*I recommend this blog entry by Dorji Wangchuk posted at Philologia Tibetica in February of 2020. It is by far the most useful discussion of the term drekang I know about.)

As for those “monotonous repetitions” — Moving over quickly to the Bön Hundred Thousand, in its first volume, at the point where it first introduces the concept “sangsaric and nirvanic böns,” it lists them all. What you see just above is its list of the sangsaric böns, all fitted on the same page. These are the terms that are slotted into the repeated statements. I’ve made a compilation of lists of sangsaric and nirvanic böns and dharmas from many different sources, but I leave those aside for now thinking I have already provided you with too much opportunity to practice the Perfection of Patience.

Now I’m moving back to the first of the three Eight Elements commentarial texts by Lhari Nyenpo. This is the very passage that initiated my bewilderment and fascination with the word drekang, although it appears a few other times in the three texts. I’ll try to translate this brief passage. The mchan-notes, because they are rubrics, I put in red letters and in square brackets. These originally appeared in smaller letters on a different line of the text connected by dots that may or may not be very visible. For all I know the rubrics are by the original author:

“When they are all added up, there are 126 [the list of both sangsaric and nirvanic böns], while the (Nine) Yungdrung Limbs are neither listed nor put in repetition statements [missing in the lists and the repetition statements, they were added.]”

Here in this pre-Mongol era Tibetan text we find the basic vocabulary for the two things involved in the text-generation process for making those lengthy repetition passages found in all the longer versions of the Wisdom Scriptures: first the enumeration or just the ‘list,’ and secondly the ‘repetition statements.’

I don’t want to say that Lhari Nyenpo was the first to use the term drekang without qualifying the statement. It’s easy to check this by doing first an exact and then a fuzzy search in the Kanjur and Tanjur database from Vienna. Doing so establishes that the term appears only once as such in the Kanjur and Tanjur, and this is in a work by the Kashmir Buddhist master Dharmaśrī. We don’t know much about him, just that he came to Tibet as a student accompanying the Indian Buddhist master Vajrapāṇi, b. 1017 (Blue Annals, p. 859), which does help verify the 11th-century date for him and his Tibetan co-translator Ba-reg Lotsāwa. Dharmaśrī wrote nothing other than these two interesting Prajñāpāramitā commentarial works, the one in question here (the second one listed just below) being on the Hundred Thousand. It’s quite a significant passage that deserves more attention, just not right now.

— Prajñāpāramitākośatāla (Shes-rab-kyi Pha-rol-tu Phyin-pa’i Mdzod-kyi Lde-mig). Tôhoku no. 3806. Dergé Tanjur, vol. DA, folios 228r.4-235r.7. Translated by Ba-rig (i.e. Ba-reg).

— Śatasāhasrikāvyākhyā (Stong-phrag Brgya-pa’i Rnam-par Bshad-pa). Tôhoku no. 3802. Dergé Tanjur, vol. TA, folios 204r.3-270r.7. Authorship given with a question mark.

An exact search finds nothing else in the Tanjur. Still, if we do a fuzzy search for the phrase grangs ’gres (a contraction of the longer phrase grangs dang ’gres rkang) as we find in Lhari Nyenpo’s text, we do find significant passages that are in the same semantic ballpark. Enough of that.

I’ve finished giving my conclusions, as far as I’m going to give any today, but I do want to end with a quick tour of the Chos literature on drekang. That way I hope you will be able to take away with you a memory of the word drekang and the idea that it is one mechanical memory tool among still others in the toolboxes of ritual reciters intending to generate a consciousness of the unstable, ineffable, insubstantial, relative, interdependent, interconnected, unreifiable, unquantifiable, insubstantial and indeed empty nature of all dharmas both sangsaric and nirvanic. This tool went right on working from somewhere during the half millennium of orality through two millennia of book culture until today. And today we don’t know where we are unless (because?) we’re in front of a screen, almost as if Fahrenheit 451 has come true a few centuries earlier than its author predicted.

§ § §

Appendix on the Most Relevant Tibetan Literature

Continue only if you are interested in [1] later literature relevant to the earliest Tibetan translations of Perfection of Wisdom in One Hundred Thousand Lines and [2] the Gelugpa literature about drekang. I’ll ask whoever doesn’t find the subject compelling to go find something better to read.

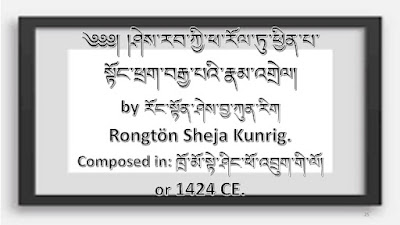

I may have been first to introduce this Rongtön text to the academic world when I spoke of it in my 1991 dissertation (on basis of a 1985 Indian reprint), and since then nobody mentions it. That is not only odd but a pity since it has to be crucial for anyone interested in the Wisdom Scriptures in their Tibetan forms, but also for the history of textual criticism or ‘philology’ as a Tibetan practice and, needless to say Manuscriptology.

Even if I won’t make much hay out of it, Rongtön was educated as a Bönpo in the far eastern end of the high plateau until age 18 when he was sent to study in Central Tibet. He would in his later years become one of the most prominent Tibetan intellectuals, as a member of the Sakya School, basing himself in a monastery in Penpo (འཕན་པོ་) Valley north of Lhasa. Modern-day Bönpos regard him with much respect.

In his text Rongtön identified five different text-historical levels in the translations of the Hundred Thousand, some of them preserved in manuscripts kept in specific places. He names no less than 65 locations where named and/or described manuscripts could be found. And he distinguishes them for us by identifying their different numbers of chapters, among other things.

The next text I stumbled upon, quite recently, in one of those enormous sets of early Kadampa works compiled and reprinted in recent years by the Peltsek group in Lhasa. It was written at an unknown date by a person I haven’t positively identified yet, but I think it may be as old as Rongtön’s text, or even a century or two older. It was, if you can read the small cursive letters on the slide, specifically written because of the need to edit the Tibetan text of the Hundred Thousand. For most of it the author goes chapter by chapter reporting to us about specific additions and omissions that characterize particular existing manuscripts. Believe it or not, he says he consulted with no fewer than 184 old examples of the Hundred Thousand. What comes next is still more amazing to hear if you are a Tibetan manuscriptologist: He says that the birchbark manuscript lists 160 Samādhis, while the others have no more than 119, and some as few as 12 or 21. Who imagined there might have been birchbark manuscripts of the Hundred Thousand in Tibetan? We do know of birchbarks with Tibetan on them, but only short dhāraṇīs enclosed in imperial era images as part of their consecration rites. Well, there is that seemingly exceptional bound codice made of birchbark that was displayed (and may still be displayed) in the modern Tibet Museum in Lhasa, but it's in Sanskrit written in an Indic script.

Anyway... It shares similar aims with Rongtön’s, uses similar editorial vocabulary including drekang and related terms. And perhaps most intriguing for us, this text, too, mentions the Hundred Thousand manuscript once kept at the Imperial period Karchung Temple. This is the one I mentioned before, the one that survived a fire to be rediscovered in the 21st century. Just look at p. 382, where it is discussing a section of a repetition statement in the bam-po section no. 10 that is missing in some examples. It then says we can know this because "it is actually to be found in other examples such as the Hundred Thousand manuscript that was not burned in the fire at Karchung."*

(*Kawa, in his article, says this should be the one known elsewhere as Sbug-’bum, that would have had four volumes only. But Rongtön calls this Karchung set the Yugs-’bum, and says it has six parts (dum-bu), listing it among 17 then-existing examples of medium-lengthed imperial translations, all of them in either four or six parts.)

Gelugpa literature about drekang:

This one is written by the famous regent ruler of Tibet at the end of the 17th century. This may be the earliest in the series of Gelukpa authored drekang texts, but unfortunately it hasn’t come down to us. It may have been 71 folios in length, which would make it by far the longest one I’ve known about. I don’t know why Gelukpas took over discussions on this topic, but the fact is they did, so to cap things off, I will run through the list of them attempting to put them in chronological order. All five of them are available, and for most part extremely short.

This one by a very famous incarnate Lama of Amdo tells us at the end that it is extracted from Rongtön’s work (and only a very small part of it, too, since about all we have here is the list of sangsaric and nirvanic dharmas).

I still haven’t studied this one closely, but I hope to. It is relatively long and written in a clear style.

Here you see the one by Longdol Lama. Back before the 1970s people locked in universities throughout most of the world used to quote Longdol Lama a lot, since his Collected Works was likely to be the only such set available to them. Now we have thousands of them.

These last two belong to the 20th century:

Some, not all, of the works mentioned or not mentioned

Note: For an overview of Wisdom Scriptures of the non-Bön kinds and studies based on them, you could read Conze’s 1978 monograph on the subject, or even better, start with Apple’s essay and then move on to Zacchetti’s, at least its first parts.

Mark Allon, Style and Function: A Study of the Dominant Stylistic Features of the Prose Portions of Pali Canonical Sutta Texts and their Mnemonic Function, International Institute for Buddhist Studies (Tokyo 1997).

Mark Allon, The Composition and Transmission of Early Buddhist Texts with Specific Reference to Sutras, Hamburg Buddhist Studies no. 17, Projekt Verlag (Bochum 2021).

Bhikkhu Anālayo, Early Buddhist Oral Tradition: Textual Formation and Transmission, Wisdom Publications (Somerville 2022).

Bhikkhu Anālayo, “Early Buddhist Orality and Challenges of Memory,” an oral presentation for the International Association of Buddhist Studies (Seoul, August 2022). Look here.

James B. Apple, “Prajñāpāramitā,” a 20-page entry in Arvind Sharma’s Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, a pre-published draft from a book that was supposed to appear in the spring of 2015. The book did appear in print in 2019, but the price of purchase plus mailing is beyond the budgets of 99% of us humans. With BookDepository (long bought out by Amazon) with its free mailing shutting down later this month, book lovers of the whole world will be tightly squeezed in the vices of Amazon/DHL until their nefarious plan to shut down book culture altogether is achieved (I’m guessing sometime next year if not already).

Ray Bradbury, “Ray Bradbury Reveals the True Meaning of Fahrenheit 451: It’s Not about Censorship, but People Being Turned into Morons by TV,” an entry at the website Open Culture (August 10th, 2017). The book bannings by the Florida governor deSantis in recent weeks can be brought into this discussion. Perhaps Bradbury is right in saying that teachers and librarians, if they tacitly resist by just putting those books back on the shelves, will win over tyranny in the end.

Edward Conze, The Prajñāpāramitā Literature, The Reiyukai (Tokyo 1978). I recall that Conze once mentioned the title of the Eight Elements scripture of Bön, but with nothing further to say about it. I suppose it may have been in this book. Anyway, it isn’t all that important.

Ding Yi, “‘By the Power of the Perfection of Wisdom’: The ‘Sūtra-Rotation’ Liturgy of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā at Dunhuang,’ Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 139, no. 3 (July 2019), pp. 661-679. There are interesting passages in Chinese that can be used to draw a picture of Dunhuang Buddhist recitation rituals. Incidentally, on p. 663 are some important references to Tibetan-language Imperial Hundred Thousand (Bla-’bum) manuscripts

Brandon Dotson, “Failed Prototypes: Foliation and Numbering in Ninth-Century Tibetan Śatasāhasrikā-Prajñāpāramitā-Sūtras,” Journal Asiatique, vol. 303, no. 1 (2015), pp. 153-164.

David Drewes, “Dharmabhāṇakas in Early Mahāyāna,” Indo-Iranian Journal, vol. 54 (2011), pp. 331-372.

David Drewes, Mahāyāna Sūtras and Their Preachers: Rethinking the Nature of a Religious Tradition, doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia (2006). Not seen.

Franz-Karl Ehrhard, “In Search of the bKa' 'gyur lung: The Accounts of the Fifth Dalai Lama and His Teachers,” contained in: Volker Caumanns et al., eds., Gateways to Tibetan Studies: A Collection of Essays in Honour of David P. Jackson on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday, Indian and Tibetan Studies no. 12.1, Department of Indian and Tibetan Studies, Universität Hamburg (2021), vol. 1, pp. 205-232.

Charlotte Eubanks, “Voice as Talisman: Theorising Sound in Medieval Japanese Treatises on the Musical Art of Sutra Chanting,” Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies, online journal (2023), in 27 pages.

Furusaka Koichi, “Adhimukti and Sūtra-Recitation of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā-prajñāpāramitā,” contained in: ICEBS editorial board, ed., Esoteric Buddhist Studies: Identity in Diversity, Koyasan University (Koyasan 2008), pp. 267-271.

Natalie D. Gummer, “Listening to the Dharmabhāṇaka: The Buddhist Preacher in and of the Sūtra of Utmost Golden Radiance,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 80, no. 1 (March 2012), pp. 137-160.

———, “The Senses of Performance and the Performance of the Senses: The Case of the Dharmabhāṇaka’s Body,” Journal of Indian Philosophy (2022). Not yet seen.

Kazushi Iwao, “On the Roll-Type Tibetan Śatasāhasrikā-prajñāpāramitā Sūtra from Dunhuang,” contained in: B. Dotson et al., eds., Scribes, Texts and Rituals in Early Tibet and Dunhuang, Ludwig Reichert (Wiesbaden 2013), pp 111-119. Among other matters, this shows that very early Tibetan versions of the Hundred Thousand could be brought to the Dunhuang area from Central Tibet for copying purposes.

Kawa Sherab Zangpo (སྐ་བ་ཤེས་རབ་བཟང་པོ་), “Comments on Emperor Khri lde srong btsan’s Bla ’bum” (བཙན་པོ་ཁྲི་ལྡེ་སྲོང་བཙན་གྱི་ཐུགས་དམ་བླ་འབུམ་སྐོར་ངོ་སྤྲོད་ཞུ་བ་), contained in: Hildegard Diemberger and Karma Phuntsho, Ancient Treasures, New Discoveries, International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies (Halle 2009), pp. 55-72. This Tibetan-language essay is supplied with a relatively long resumé in English.

Jinah Kim, “Iconography and Text: The Visual Narrative of the Buddhist Book-Cult in the Manuscript of the Ashṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra,” contained in: Arundhati Banerji & Devangana Desai, eds., Kalādarpaṇa: The Mirror of Indian Art, Aryan International (New Delhi 2008), pp. 250-268. Find it here.

Marcelle Lalou, “La version tibétaine des Prajñāpāramitā,” Journal Asiatique, (July-September 1929), pp. 87-102.

———, “Les manuscrits tibétaines des Grandes Prajñāpāramitā trouvés à Touen-Houang,” contained in: Silver Jubilee Volume of the Zinbun-Kagaku-Kenkusyo, Kyoto University (Kyoto 1954), pp. 257-261.

———, “Les plus anciens rouleaux tibétains trouvés à Touen-houang,” Rocznik Orientalistyczny, vol. 21 (1957), pp. 149-152.

———, “Manuscrits tibétains de la Śatasāhasrikā-prajñāpāramitā cachés à Touen-houang,” Journal Asiatique, vol. 252, fasc. 4 (1964), pp. 479-486.

Lewis Lancaster, “The Oldest Mahāyāna Sūtra: Its Significance for the Study of Buddhist Development,” Eastern Buddhist, n.s. vol. 8, no. 1 (May 1975), pp. 30-41. Here the author summarizes in an accessible way his doctoral research drawing on the evidence of early Chinese translations.

Sylvain Lévi, “Sur la récitation primitive des textes bouddhiques,” Journal Asiatique (May-June 1915), pp. 401-447.

Sodo Mori, “The Origin and the History of the Bhānaka Tradition,” contained in: Ananda: Papers on Buddhism and Indology a Felicitation Volume Presented to Ananda Weihena Palliya Guruge on his Sixtieth Birthday (Colombo 1990), pp. 108-111.

Richard F. Nance, “Indian Buddhist Preachers Inside and Outside the Sūtras,” Religion Compass, vol. 2 (2008), pp. 1-26.

Ryan Richard Overbey, Memory, Rhetoric, and Education in the Great Lamp of the Dharma Dhāraṇī Scripture, PhD dissertation, Harvard University (Cambridge 2010). I’ve just found out I could access this, so I’ll have to let you know what I find in it another time. It’s unbearably rich, and ought to be a book already.

Gemma Perry, Vince Polito, Narayan Sankaran, & William Forde Thompson, “How Chanting Relates to Cognitive Function, Altered States, and Quality of Life,” Brain Sciences, vol. 12 (2022), in 22 pages. “Chanting has been found to decrease stress and depressive symptoms, increase focused attention, increase social cohesion, and induce mystical experiences.” Excited scientists think they have discovered something the humanists regard as very old news. Nothing new in that.

Gemma Perry, Vince Polito, & William Forde Thompson, “Rhythmic Chanting and Mystical States across Traditions,” Brain Sciences, vol. 11 (2021), in 17 pages. Both articles are offered as an alternative view for all those who dismiss recitation and chanting as simply boring and to no good effect. I have no idea if early Buddhist scripture recitations were ‘monotonous’ or not. I prefer the idea that they were in some degree melodious, delivered by persons with mellifluous voices, who would tend to draw out syllables for emphasis, perhaps with still other performative techniques. Sylvain Lévi long ago showed how Buddha distanced the chanting of his monks from Vedic chanting by making it different. I think more recent chanting traditions such as Shingon’s shômyô are worth looking into, since a more recent chanting tradition could awaken us to a larger realm of possibilities (see the essay by Eubanks). We might miss out by over-presuming primeval monotones.

Richard Salomon, Indian Epigraphy, Oxford University Press (Oxford 1998).

Eviatar Shulman, “The Play of Formulas in the Early Buddhist Discourses,” Journal of Indian Philosophy, vol. 50 (2022), pp. 557-580. For an oral presentation with a nearly identical title, delivered at Center for Buddhist Studies (Berkeley, June 2021), go here.

———, “Orality and Creativity in Early Buddhist Discourses: Stock Formulas as an Aspect of the Oral Textual Culture of Early Buddhism,” contained in: Natalie Gummer, ed., The Language of the Sutras, Mangalam Press (Berkeley 2021), pp. 187-230.

Peter Skilling, “Redaction, Recitation, and Writing: Transmission of the Buddha’s Teaching in India in the Early Period,” contained in: Stephen C. Berkwitz, Juliane Schober and Claudia Brown, eds., Buddhist Manuscript Cultures: Knowledge, Ritual, and Art, Routledge (London 2009), pp. 53-75.

David Snellgrove, Himalayan Pilgrimage: A Study of Tibetan Religion by a Traveller through Western Nepal, Prajñâ Press (Boulder 1981).

Stefano Zacchetti, “Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras,” an entry in Jonathan Silk, ed., Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhist Online, about 65 pages in length, available through a subscribing institution. The author’s treatment of intertextual relations and chronology is more up to date than Conze’s, often emphasizing the ”fluid nature” of these scriptures. In the section entitled “The Larger Prajñāpāramitā Subfamily” is an attempt to account for the “endless repetitions” of the Larger Prajñāpāramitās, but also the dynamism of the texts as “breathing living entities.” And he finally spares some words on their “performative nature.” Even more intriguingly for myself, he speaks of a “textual generative principle.” Indeed, we can imagine that to some degree the texts are forming and evolving as part of the recitation practice. Not so much in evidence is the often assumed opposite: the practice being commanded, authorized or sanctified by the text. But of course that’s there, too.

— — —

Note: This is a revised version of a presentation given in Hamburg in March 2023. It might be regarded as a preliminary draft of a forthcoming paper, nothing can be certain.

Another note: If news of early birchbark manuscripts preserved in Tibet leaves you in shock or disbelief, two different ones are illustrated in the five-volume set Precious Deposits, Morning Glory Publishers (Beijing 2000), vol. 1, pp. 113-116, 144-145. Both are Sanskrit language and written in an Indic script. A birchbark version of one of the Larger Prajñāpāramitās was found in Gilgit and dated to the 6th or 7th centuries (also in Sanskrit), but it was preserved in what is now Pakistan, not in Tibet. More examples could be given with a little more research.

Still another note: Practically all the Prajñāpāramitā scriptures were translated long ago by Edward Conze. At the moment the 84000 Project is pushing to place in our hands a complete translation of the entire set of them over the next six years. Unlike Conze, they will translate every last word without abridging. 84000 has already put up one work that absolutely bedazzles me — Gareth Sparham’s translation of the gigantic Daṃṣṭrasena (Mche-ba'i-sde) commentary. It covers the Large Prajñāpāramitās, the 100,00, the 25,000, and the 18,000. The reference to the Tibetan version of it is:

All Three of Lhari Nyenpo’s Eight Elements Compositions Transcribed

Source: Khams-brgyad Stong-phrag Brgya-pa: Bonpo Prajñāpāramitā Text revealed by Gshen-chen Klu-dga’, “from a rare manuscript collection from Klu-brag Monastery in Mustang (Nepal),” Tibetan Bonpo Monastic Centre (Dolanji 1975), in 16 vols., at vol. 1:

[1] gshen rgyal 'bro ba'i bla mar phyag 'tshal lo //

'dir g.yung drung bon gyi bstan pa'i snying po / bde bar gshegs pa'i gsung / theg pa chen po yum gyi don zab mo stong pa nyid dang mngon par rtogs pa lam gyi rim pa bcas brjod byar ston pa'i 'bum 'di nyid rdzogs pa'i sangs rgyas gshen rab mi bo kun las rnam par rgyal ba de nyid kyis phun sum tshogs pa'i gnas brgyad du bzhugs te gsungs pa'i tshul ni zhu 'khor gshen brgyad kyis mchod pa'i rdzas brgyad phul nas / khams chen po brgyad gsungs par gsol ba btab / bka' yi bsdu ba rim pa gnyis su [2] mdzad pa'i dang po gsas khang dkar nag bkra gsal du ston pa sangs rgyas kyis thabs kyi sangs po 'bum khri dang shes rab kyi phul ston pa gshen rab zung du sbrel nas gsung rab rnams rin po che sna lnga'i glegs bam du sbams te rjes bzhag mdzad /

gnyis pa ni ston pa mya ngan 'das 'og tu bsdu 'khor g.yung drung sems dpa' bcu gsum gyis bsdus te mdzad / de rjes gdung 'tshob ston pa mu cho ldem drug phebs te gsung rab thams cad mdo 'bum rgyud mdzod sde bzhi ru phyes / lha klu mi gsum gyi slob ma bsam gyis mi khyab pa bskyangs / de dag las mchog tu gyur pa 'dzam bu gling gi rgyan du gyur pa drug byung / de rnams [3] kyis skad gnyis shan sbyar nas rang rang gi yul du bsgyur te g.yung drung bon gyi 'khor lo bskor nas sems can bsam gyis mi khyab pa smin grol la bkod do /

gzhan yang gdung 'tshob chen po dang rgyan drug bcas pa'i slob mar gyur pa grub pa'i rig 'dzin lha gshen yongs su dag pa / rgyal gshen mi lus bsam legs / klu grub ye shes snying po dang bcas pas 'bum sde 'di rnams kyi tshig don la rab dbang thob par mdzad cing bzhugs pa de rnams kyi zhabs la gtugs pa'i slob ma rgyal gshen gyi gdung brgyud 'dzin pa'i skyes mchog nam mkha' snang ba mdog can gyis gzhung 'di dag la sgro 'dogs chod par mdzad / bla ma 'di bod [4] rgyal gnya' khri btsan po dang / mu khri btsad po yab sras gnyis kyi mchod gnas su bzhugs / mu khris zhang zhung gi yul nas mkhas la brgya rtsa gdan drangs te bod du bon sde bzhi bcu rtsa lnga btsug / khyad par du bla na med pa'i bon sde rnams bod du dar te / lta ba bla med / theg pa bla med / spyod pa bla med / 'bras bu bla med / don dam bla med rnams so //

de rnams kyi sngon du rgyal po gnya' khri'i dus su bod du dar ba'i rgyu yi bon shes pa can bcu gnyis dang 'di rnams bod rgyal gnam gyi khri rabs bdun pa gri gum gyi bar du dar rgyas su yod cing / rgyal po de'i blo la gdon zhugs nas ru bzhi bod kyi sa skor du rgyu yi bon kha shas ma gtogs [5] pa phal cher bsnubs / de'i dus su rgyal po bka' btsan nas bon gshen rnams bod yul ru bzhi la bzhugs pa'i dbang ma byung ste rang thob kyi bon sde dang bcas bod kyi phyi mthar gshegs dgos pa byung bas / de'i skabs slob dpon stong rgyung mthu chen sogs mkhas pa mi bzhi lho dam sgro nag po zhes lho 'brug gi sa char bstan pa spel bar dgongs te gshegs pas bod kyi mgur lha dang brtan ma sogs ma dgyes te kha bas lam bgags nas gnas su gshegs ma grub pas bon rnams lam bar gyi mtsho rnga'i brag ka ru na sbas so //

phyi nas gshen bstan rin po che dar ba'i dus la babs tshe pan grub [6] gong mas byin gyis brlabs pa'i skyes mchog sprul pa'i sku gshen chen klu dga' de nyid kyis 'brig mtshams mtha' dkar nas gter zhal phyes pa'i bon sde du ma byung zhing / khyad par du khams brgyad gtan la phab pa'i 'bum dum pa bcu drug gi bdag nyid can 'di byung / gter shog las cog la g.yung drung skyid kyis bshus nas gshen chen klu dga' la tshar gcig phul de la BSE GLEG CAN zer / g.yung drung skyid khong rang gi ched du yang tshar gcig bzhengs par 'BUM DMAR grags / khams chen NAG PHRAN MA zhes snag tsha kho nas bris pa gter shog gi bu dpe de da lta'i bar du zhu ri zhing dgon du bzhugs /

[7] gshen gyi gter dpe dngos ni bla ma gshen zhing khams gzhan du gshegs skabs gshen sras rnam gnyis na lon tshe phyir 'bul bar byas te zhu g.yas legs po la bcol bas zhu yi gsung rab rnams dag pa'i khungs kyang byed pa'i srol yod / gter dpe las bshus pa'i dpe gsum tsam 'phel ba rnams rme'u lha ri gnyan pos bsdur nas dag bshar mdzad pa'i bar khyad rnams zin bris su bkod pa zur du yod pa bzhin no //

gzhung 'di yis dngos bstan stong nyid kyi rim pa bstan pa dang sbas don mngon rtogs kyi rim pa bstan par mkhas pa rnams zhal mthun yang / stong nyid ni kha cig gis dbu ma rang [8] rgyud pa'i lta ba bstan pa yin par bzhed / kha cig gis dbu ma thal 'gyur gyi lta ba bstan par bzhed do //

gzhan sde yum don 'chad pa po rnams kyis rdzogs chen yongs rtse'i lta ba la blo ma phyog pas phar phyin gzhung gis rdzogs chen gyi lta ba bstan par mi 'dod mod / rang sde'i yum don 'grel mdzad rnams kyang gzhan gyi zer sgros la ches zhen nas rang gi thun mong ma yin pa'i yum don dang / khyad par du rig pa'i khams nas bstan pa'i rang rig pa'i ye shes 'di ni ma bgos spyi la bzhag pa'i nor bu rin po che'o // zhes pa'i tshig rnams kyis bla med rdzogs pa chen po'i lta ba bstan [9] par ma 'grel bas gzhung don la thag 'gyangs su song ngam snyams //

khams re re'i ched du bya ba'i gdul bya la ltos te khams re res lam gyi rim pa cha tshang du ston pa dang / khams brgyad kyis ched du bya ba'i gdul bya la ltos te khams brgyad kas lam rim cha tshang gcig tu ston pa sogs gdul bya la ltos nas bzhag pa yin par gsungs /

kho na re 'di phar phyin gyi theg pa'i gzhung gi gtso bo yin pas sngags kyi lta ba ston par 'dod pa mi 'thad do zer na / rang lugs kyi mdo 'bum rgyud mdzod rnams kyis gzhi gtan la 'bebs skabs gzhi'i gnas lugs rang [10] byung ye shes tsam gtan la 'beb pa 'dra zhing de'i thabs kyi cha dang lta ba gtan la 'beb tshul lta ba rtogs tshul de nyams su len tshul sogs sgo gzhan mi 'dra ba du ma yod par bzhed /

dper na za 'og gi gzhi sngo shas che zhing de la tshon dang ri mo mi 'dra ba'i rnam 'gyur ji snyed so so na bkra ba bzhin no zhes gsungs /

gzhung 'dis rdzogs chen gyi lta ba gtan la phab na theg rim 'chol ba'i skyon med de / rdzogs chen gyi lta ba gzhung 'di'i brjod bya'i gtso bo byas nas ma bstan pa'i phyir dang / gong ma'i lta ba g.yar nas bstan pa'i phyir / zhes gsungs // dge'o //

* * *

[11] khams brgyad kyi phyi mo gtug pa'i dag yig bzhugs /

sgo bzhi mdzod lnga'i bon la phyag 'tshal lo / bla 'bum dpe gsum la gtug pa'i ti ka / BSE KLAG CAN la skye mched kyi gzungs yongs yul du 'dug BLA 'BUM na med / g.yung drung sems dpa'i spyod pa la sogs srid pa'i 'brel la phal cher drug po chad / nag phran ma nas bam po le'u 'ong pa yo na mtshal gyi g.yung drung re yod / rten 'brel regs tshor gnyis chad pa bsab 'dug / BYA BRA MA la snang / srid pa de nas srid len 'byung ba bcos 'dug / yod ces bya ba la spyod na mtshan ma la spyod pa'i 'gres la NAG PHRAN na thar pa'i lam bzhi rnam grangs brkyang nas 'dug / BLA 'BUM na bon thams cad g.yi zhing rtsol spyod pa'i 'gres na stobs kyi bla med chad / NAG PHRAN MA nas snying rjer [12] song / 'khor 'gres tha ma rga shir thal / rga shi mnyam pa thugs rjes byin gyis brlabs / ye ma byung ma skyes skye ba med pa'i 'gres la mya ngan las 'das pa ma / NAG PHRAN la skye med gdod de bzhin nyid bya ba'i rkyang pa re yod / BLA 'BUM dang BSE KLAG CAN la med / khams brgyad kyi don mya ngan las 'das pa'i don 'dres tshar brgyad skyel ba dang / BSE KLAG CAN la dbyings sngon la 'ong / rig pa'i phyi na 'dug / BLA 'BUM na ma 'khrug skye ba med na rgyun khams kyi 'gres na mya ngan las 'das pa lnga lnga las med / BLA 'BUM la 'du byed dang lus kyi 'dus te regs pa BYA BRA MA la med / ma srid pa'i srid pa'i 'gres la / BLA 'BUM la thar pa'i lam brgyad kyang med BYA BRA MA la yod / [13] snang ba rin po che gshen gyi smon lam mi mgon rgyal po man chad med / sems dpa' gnyis brtsegs su yod / mtha' las 'das pa'i 'dres kyi mya ngan las 'das pa gnyis la chad / chen po stong pa'i 'gres la sogs pa'i lnga lnga chad do //

dngos po med pa'i ngo bo nyid stong pa'i 'gres la BYA BRA MA la lce yi rnam par shes pa'ang chad / BLA 'BUM na yod rin po che yi 'gres la rgyun bzhugs yod / tshul khrims kyi le'u la ma rtog pa'i dbang gi zer / BLA 'BUM la ri rab kyi rtse nas kun 'debs pa la song pa'i dgu po chad / BYA BRA MA la yod / BYA BRA MA la gsad pa'i nang nas thu ba sems gsad pa tshar nas bzod par song / tshul khrims kyi 'gres bu thung chad / snang khams yo la rgyun bzhugs yod / [14] rnam dag 'gres la spyan gyi 'dabs par bya na 'dug / rnam par mi rtog pa'i khrus la chen po stong pa dang dam pa stong pa gnyis chad / BYA BRA MA la yod /

stong pa'i 'gres la chad med yod / de bzhin nyid kyi snying po sgom pa la BLA 'BUM las dris tshigs med / ma 'ong mi 'gro 'gres la rang bzhin med pa stong pa nyid chad / BLA BRA MA la yod /nga rgyal gyi 'gres la mtshan ma med pa la 'jug la chad / BLA 'BUM la yod / rig pa'i khams la yang dag par rig pa'i khams la yod / dbyings khams kyi mu med pa sangs rgyas kyi 'gres la rnam par shes pa'i khams gcig yod / de yi thams cad BLA 'BUM la dngos po yod pa bsad gda' / de nas yang bsos nas 'dug / mnyam pa'i 'gres la 'khor ba dang mya ngan bya ba'i 'gres la thams cad phyed [15] zhes bya ba med pa'i 'gres la bla na med par phyin pa drug las med / BYA BRA MA la stong nyid bco brgyad tshar gcig la phyi mnyam pa nyid dang / nang mnyam pa nyid la sogs zer ro // phyi nang stong pa nyid la khyab pa chen po'i mnyam pa nyid dang zer ro // BLA 'BUM la stong pa rang du 'dug / stong pa nyid stong pa nyid khyab pa chen po'i mnyam pa nyid zer ro // mnyam pa nyid la phal cher du bla med drug 'dug / 'gres pa med / 'gres yo tshang / mnyam pa'i khams la 'du shes 'du byed gral nor yod / tha ma bcos pa'i le'u la bon nyid mi 'gyur ba'i le'u zer /

bon thams cad phyi nang gnyis su med par don la lhun gyis grub pa yan chad {KA} pa / [bam po bcu dgu pa'o /]

srid pa rdzogs pa {KHA} pa [bam po nyi shu rtsa gcig] [16]

nor bu rin po che mchod par byed pa yongs su mchod par byed pa yan chad {GA} pa / [bam po nyi shu /]

rin chen rdzogs pa {NGA} pa / [bam po nyi shu rtsa drug]

snang ba shes rab rdzogs pa / {CA} pa / [bam po nyi shu rtsa bzhi /]

snang ba rdzogs po {CHA} pa / [bam po nyi shu rtsa drug /]

stong pa'i dbang po rdzogs pa / {JA} pa / [bam po nyi rtsa bzhi]

stong pa rdzogs pa / {NYA} pa / [bam po nyi shu rtsa gnyis /]

so so zhe sdang gi ngo bo / {TA} pa / [bam po nyi shu rtsa gcig /]

so so rdzogs pa / {THA} pa / [bam po bcu dgu pa'o //]

rig pa'i zhus pa / bla na med pa yang dag par rdzogs pa / ci yang 'gyur ba yan lag / {DA} [bam po nyi shu rtsa gnyis /]

'byams yas pa'i mdor rdzogs pa / {NA} [bam po nyi shu pa'o]

ye shes kyi 'bras bu thob pa la sogs pa / {LA} [bam po nyi shu rtsa gsum pa'o /}

dbyings rdzogs pa / {PHA} [bam po nyi shu rtsa gsum pa'o /]

ngang dang rang bzhin gsum gyi [17] stong pa nyid las bcad pa / {BA} [bam po nyi shu rtsa drug]

mnyam pa rdzogs pa / {MA} [bam po nyi shu rtsa lnga pa'o /]

khams chen po brgyad la / le'u brgyad cu gya gnyis / bam po sum brgya drug cu / glegs bam bcu drug du brdeb pa'i spyi don mdor bsdus pa'o / sprul sku lha ri gnyen pos phyi rabs don du mdzad pa 'dis kyang / rgyal ba'i bstan pa phyogs thams cad 'phel zhing rgyas par 'gro don dpag med 'grub par shog / bkra shis zhal dro byin che'o // //

* * *

[19] khams brgyad kyi zhu thig rnam dbye grangs su bkod pa bzhug //

gshen rgyal zhabs la phyag 'tshal lo //

sprul sku lha la skyabs su mchi //

[mchan: 'khor ba mtha' yas pas phyag tu phul lo / ring ba'i rgyu ni sngon gyi sprul sku ste nye ba'i rgyu ni khro tshangs pa'i sprul sku'o //]

khams brgyad gtan la phabs pa'i 'bum / spyi dang khams gnas yul / zhu ba zhu don gzhi rtse gling / le'u bam po la 'dris rgya / ming tshig shad sdom stong phrag grangs / ston pa yon tan ma lus rdzogs / sku yi che ba nyer gcig dang /

[mchan: bya ba byed pa byas pa sogs 'gro ba sems can gyi don mthar phyin par mdzad pa'i slad du spyi bo'i gtsug nas zhabs kyi mthil du ma yan chad du'o / khyab pa chen po ston pa'i rang bzhin du mkhyen pa'i sogs / zer stong phrag grangs med pa ye shes sems dpa' rigs dur 'khor /]

'od zer 'bum phrag grangs med spros / mkhyen pa'i ye shes drug bcur lan / srid pa rin chen rgyun snang ba stong pa so sor rig pa dang / dbyings nyid

[mchan: srid skal snang stong pa rig dbyings mnyams khams ces so /]

[20] mnyam pa'i khams brgyad do //

yul ni ri rgyal lhun po'i gnas /

[mchan: phyi ltar shel gyi rdo ring gi rtse nang ltar ston pa'i sku la thug /]

rin chen grangs ma spungs pa'i gling /

[mchan: phyi ltar klu yi pho brang nang ltar ston pa'i thugs dgongs 'dod kun 'byung ba'o /]

g.yung drung gsal ba 'od kyi gling /

[mchan: phyi ltar chu mig brgyad cu rtsa gnyis 'go bo nang ltar thugs nyid gsal ba'o /]

bar ti mun pa g.yung drung gling /

[mchan: phyi ltar mun pa'i gling nang ltar 'gro ba'i ma rig blo /]

mun ming khyud mtsho mu yang gling /

[mchan: phyi ltar rol mtsho nang ltar thugs nyid rgya mtsho'i klong lta bu'o /]

dar dkar gur 'og rgya mtsho'i gling /

[mchan: phyi ltar klu yul nang ltar thugs nyid rnam par dag pa /]

'phel 'grib med pa g.yung khyim bdun /

[mchan: phyi ltar mu khyud 'dzin gyi rtse ltag nang ltar dgongs pa 'phel 'grib med pa /]

rin chen 'phrul snang gzhal yas brgyad /

[mchan: phyi ltar nam mkha' snang srid tha mi dad pa'i gzhal yas nang ltar thugs nyid mnyam pa'i ngang /]

[21] zhu ba drang don du zhu ba po brgyad la bon mi 'dra ba brgyad gsungs kyang don gcig go /

YID KYI KHYE'U CHUNG dang / [mchan: ser po bzhi bkur hos ru bsnams pa /]

GTO BU 'BUM SANGS / [mchan: dkar po chag shing bum pa 'dzin pa /]

GSAL BA 'OD LDAN / med khams stong pa [mchan: mthing ga me tog bsnams pa /]

rje TSHANGS PA GTSUG PHUD / [mchan: dkar ljang u dum 'bar ba'i me tog 'dzin pa /]

KLU MO MA MA [mchan: dkar ljang sbrul gdeng chu skyes /]

GTSUG GSHEN RGYAL / [mchan: dkar ser g.yung drung skos shing /]

'PHRUL BON GSANG BA DANG RING gis / [mchan: sngo dmar rgyal mtshan nor bu /]

zhu don [mchan: dkar po 'khor lo sa le sgron me dang 'phrul gyi {{Note: The following text seems misplaced, and is enclosed in brackets in the original: KA dum KHA dum gnyis srid khams gtan la phab /}} yi ge yang zer bsnams pa /] skyes med gdos dag pa /

rin chen rgyun 'byung 'gag pa med / {{GA dum NGA dum rgyun khams}}

tshad med stong mthar lhung ba med / [CA dum CHA dum gnyis stong khams /]

mtshan med dngos por 'byung ba med / [22] [JA dum NYA dum gnyis med khams /]

yongs su bkag med sgrib pa med / [TA dum THA dum gnyis so so yi khams /]

cir yang ma grub dmigs pa med / [Da dum NA dum gnyis pa'i khams /]

kha gting dpag med g.yo rtsol med / [BA dum PHA dum gnyis dbyings kyi khams /]

ma bcos mnyam bzhag thig le gcig / [BA dum MA dum gnyis mnyam pa'i khams /]

gzhi rtsa 'khor 'das bdag nyid do / ['khor 'das kyi bon thams cad bdag nyid la 'dus par bstan /]

'khor 'gres bzhi bcu zhe drug nges / [mchan: rnam par shes pa'i khams dang zhe bdun mngon /]

myang 'das 'bres la grangs med 'gres / [res mang res nyung du byung /] nga bcu nga bzhi drug cu'i bar / lan gcig phyir 'ong 'bras bu nas / g.yung khams yan lag rim gyi bsnon / [rim gyis snon te bsnon lugs ni /] lan gcig phyir 'ong rgyun zhugs khams / [ma 'gag pa'i rgyun de rin po che rgyun gyi khams dang mthun /]

[23] rgyun zhugs 'bras bu snang ba'i khams / [rgyun khams du snang yod pas snang ba'i khams dang mthun /] tshad med bzhi ni stong pa'i khams / [tshad med bzhi las 'das pas stong pa'i khams dang mthun /] g.yung drung bon phye ba ma 'dres dgu / [ma 'dres pa so so'i khams dang mthun /] so sor gsal rig pa'i khams / yang dag rig pa'i khams / [yang dag rig pa rig pa'i khams dang mthun /] g.yung drung yan lag dgu dbyings khams / [g.yung drung gi yan lag dbyings khams dang mthun /] spyir sdom brgya dang rtsa drug la / ['khor 'das gnyis ka'i grangs /] g.yung drung yan lag grangs 'gres med / [grangs dang 'gres rkang la med bsnan pa'o /] gleng bslang zhus dang / [zhu ba so so'i so /] bgol ba dang / [klu mo sogs kyi bkol /] lan gnyis bka' rtsal lung bstan to / [zhus pa'i lan dang ma zhus pa ltar bshad kyi nyon cig gsungs so /]

I.

[24] le'u srid pa'i khams la brgyad / [dkyus kyi tshig 'bum rtsar shes te grangs nges so /] [srid pa'i lo rgyus dang po 'o /]

gling bzhi sems spyod zab mo dang / [mo la 'jug pa'i le'u ste gnyis pa'o / 'jug pa'i le'u ste /]

mtshan ma [gsum nas lnga bar chad 'di med do /] 'khrul rtog so so'i rjes ma rtogs / gnyis su med pa'i don lhun [bar bstan pa'i le'u ste lnga pa'o /] grub /

khams brgyad kyi rgyu bstan pa dang / [drug pa'o /]

'khor ba'i rgyu dang / [bdun pa /]

myang 'das rgyu / [brgyad pa /]

ci la 'byung bar bstan pa'o / ['di rnams mthun par krig gi yod /]

II.

rin chen rgyun khams le'u brgyad ni /

srid pa'i [dgu pa]

skal pa [bcu pa]

snang ba [bcu gcig]

stong [bcu gnyis] /

so sor [bcu gsum]

rig pa [bcu bzhi]

g.yung drung dbyings /

mnyam pa rin po che [bco lnga] nyid do //

III.

snang ba'i khams la le'u bcu bzhi /

yod med mya ngan las 'das pa dang / mi dmigs ngang la mi 'gyur gnas / sbyin pa btang [25] yod tshul khrims srung / bzod pa brtson 'grus stobs bskyed dang / snying rje smon lam thabs bsgrub pa / shes rab sems nyid rnam dag sil / don drug 'brel ba rnam dag go /

IV.

stong pa'i khams la le'u bcu ste /

rgyu ma lta bu byar med dang / g.yo ba med dang bla med dang / zag med shes rab phung po dang / thams cad mkhyen pa'i ye shes 'bras / stong pa'i dran la phyir 'ong dang / rtogs med mi dmigs stong nyid dang / de bzhin nyid bsgom stong nyid dang / rnam grangs nges don gsal ba dang / rang bzhin med par bstan pa'o //

V.

so so'i khams la le'u bdun ste /

bden pa so sor bstan pa dang / 'khor 'das so so'i dge sdig dang / dug dang ye shes so so dang / tshul khrims srung nyams so so dang / dge ba bsngos pa'i 'bras bu'o //

VI.

rig pa'i khams le'u brgyad do /

rig pa kun sbyangs kyi ngo mtshar dang / ting 'dzin zab mo'i rigs ye shes / klu mos zhus dang rig spyod 'das / rig pa sa non le'u brgyad do //

VII.

dbyings khams le'u bcu gsum ste /

ye shes 'bras bu thob par bstan / mu med 'byams yas rgya ma chad / kha gting dpag med dgos pa med / gdal pa chen po zad med dang / 'gyur med ngang nyid mtshan dpe bstan /

VIII.

mnyam pa'i khams la le'u bcu bzhi /

mnyam pa nyid kyi don bstan dang / gsal la rang bzhin med 'bras bu / dmigs med pa la bskyed dang / rtogs dkar thun mong min pa dang / rgyu 'bras mnyam pa'i don 'dus dang / mnyam pa'i don rdzogs bcos med dang / ba ga'i klong du ye shes rdzogs / stong nyid ye shes me long dang / bya ba nan tan [27] sor rtogs mnyam / ma bcos thig le gcig la bzhag //

sdom pas le'u brgya bcu gnyis (i.e., brgyad cu gnyis) / bam po srid khams zhe gcig ste / rin chen rgyun khams zhe brgyad de / yod pa'i khams la bzi bcu bdun / med pa'i khams la zhe gsum mo / so so'i khams la so dgu dang / rig pa'i khams la bzhi bcu gcig / dbyings kyi khams la lnga bcu tham / mnyam khams lnga bcu rtsa gcig ste /

de ltar sum brgya drug cu'o //

ma 'dres yan lag stong rtsa brgyad / bka' rtags phyag rgya stong rtsa'o // yi ge 'dus pa la ming byung / ming 'dus pa la tshig byung / tshig 'dus pa la shad byung / tshig bar bcu gcig shad bar gcig / shad bar bzhi la sdom tshig gcig / sdom tshig sum brgya bam po ste / sdom tshig stong phrag brgya 'bum mo // [28] khams brgyad zhun thig rnam dbye'i grangs / sprul sku lha [gur zhog pa] yis bkod pa tshar / slig tso / bkra shis //

* * *

Following are a few especially relevant sections of the Khams-brgyad text proper, including its lists of sangsaric and nirvanic böns, with added numbers that allow us to give their sum total as 108, a very auspicious number:

[1] khams brgyad gtan la phab pa stong phrag brgya pa las / dum bu dang po bzhugs //

[2] zhang zhung skad du /

[3] gu ge 'phyo smi sad wer rangs / mu ye zhi la prong tse nan // // 'phyo sang sang ste e ma ho // // bod skad du 'phrul gyi yi ge sum cus man ngag gi don bstan [4] [5] pa'i khams brgyad gtan la phab pa stong phrag brgya pa las srid pa'i gleng gzhi / tshig gi rtse mo don gyis gcod / dum bu thog ma // bam po dang po // le'u gong ma'o /

[6] 'di skad bdag gis thos pa'i dus gcig na / ston pa gshen rab mi bo ni / ri rgyal lhun po'i pho brang 'od kyi lha ri spos mthon gyi rtse mo na 'khor gshen 'phran lnga stong lnga brgya yis bskor nas / thabs gcig tu bzhugs te / 'dab chags rgyal po / bya ba byed pa byed pa byas pa / gsung lhang lhang snyan par sgrogs [7] pa / rig pa gsal ba / stobs dang ldan pa / rmad du byung ba don dang mi snyel ba'i gzungs dang ldan pa / so so'i sgo gang las ma sgribs / zag pa zad pa / nyon mongs pa med pa / ting nge 'dzin rab tu gsal ba / sems shin tu rnam par grol ba / thugs rje che ba thabs mkhas pa / gto che ba dpyad ring ba / mtshan dang [8] ldan pa dpe' yongs su 'tshogs pa / bka' rgya che ba / lung grangs mang ba / man ngag mdo sdus pa rnam pa thams cad cir kyang mkhyen pa bla na med pa yang dag pa'i don gtan la phebs pa'i / gshen rab chen po des / 'gro ba sems can gyi don mthar phyin par mdzad pa'i slad du / thugs las 'od zer 'bum phrag grangs med pa yongs su spros shing bkye'o / sku dbu'i gtsug rum nas kyang 'od zer bye ba stong phrag drug cu drug cu byung ngo / sku dpral ba'i dbyings rum nas kyang / 'od zer bye ba stong phrag drug cu drug cu byung ngo /

sku ltag pa'i rgyas rum nas kyang 'od [9] zer bye ba stong phrag drug cu drug cu byung ngo /

sku spyan mig g.yas g.yon las kyang 'od zer bye ba stong phrag drug ...

[16] zhi ba'i bdag nyid can zhes bya ba mkhyen pa'i ye shes drug bcu rtsa gcig dang ldan pa ...

[41.2] bam po dang po.

[83.7] de nas yid kyi khye'u chung gis gsol ba / ston pa lags / bon thams cad yongs su bdag nyid la ji ltar 'dus lags / gshen rab kyi bka' btsal ba / bon thams cad yongs su bdag nyid la 'dus pa ni / 'khor ba'i bon kun nas nyon mongs pa dang / mya ngan las [84] 'das pa'i bon rnam par byang ba dang gnyis so //

de gang zhe na /

[phung po lnga]

1. gzugs dang /

2. tshor ba dang /

3. 'du shes ba dang /

4. 'du byed ba dang /

5. rnam par shes pa ba dang /

[khams bco brgyad]

6. mig dang ba dang /

7. gzugs dang /

8. rna ba dang /

9. sgra dang /

10. sna dang /

11. dri dang /

12. lce dang /

13. ro dang /

14. lus dang /

15. reg dang /

16. yid dang /

17. bon dang /

[here Tre-ston has skye mched bcu gnyis]

18. mig gi rnam par shes pa dang /

19. rna ba'i rnam par shes pa dang /

20. sna'i rnam par shes pa dang /

21. lce'i rnam par shes pa dang /

22. lus kyi rnam par shes pa dang /

23. yid kyi rnam par shes pa dang /

[rkyen tshor drug]

24. mig gi 'dus te reg par shes pa rkyen gyi tshor ba dang /

25. rna'i 'dus te reg par shes pa rkyen gyi tshor ba dang /

26. sna'i 'dus te reg par shes pa rkyen gyi tshor ba dang /

27. lce'i 'dus te reg par shes pa rkyen gyi tshor ba dang /

28. lus kyis 'dus te reg par shes pa rkyen gyi tshor ba dang /

29. yid kyi 'dus te reg par shes pa rkyen gyi tshor ba dang /

['byung khams lnga]

30. rlung gis khams dang /

31. me'i khams dang /

32. chu'i khams dang /

33. sa'i khams dang /

34. nam mkha'i khams dang /

35. rnam par shes pa'i khams dang /

[rten 'brel bcu gnyis]

36. ma rig pa dang /

37. 'du byed dang /

38. rnam par shes pa dang /

39. ming dang /

40. gzugs dang /

41. skye mched drug dang /

42. reg pa dang /

43. tshor ba dang /

44. sred pa dang /

45. len pa dang /

46. srid pa dang /

47. skye ba dang /

48. rga shi dang /

la sogs pa ni 'khor ba'i bon te / kun nas nyon mongs pa'o //

1. sbyin pa'i bla na med par phyin pa dang /

2. tshul khrims kyis bla na med par phyin pa dang /

3. bzod pa'i bla na med par phyin pa dang /

4. brtson 'grus kyis bla na med par phyin pa dang /

5. bsam gtan gyi bla na med par phyin pa dang /

6. stobs kyis bla na med par phyin pa dang /

7. snying rje'i bla na med par phyin pa dang /

8. smon lam gyis bla na med par phyin pa dang /

9. thabs kyis bla na med par phyin pa dang /

10. [85] shes rab kyi bla na med par phyin pa dang /

11. phyi stong pa nyid dang /

12. nang stong pa nyid dang /

13. phyi nang stong pa nyid dang /

14. 'dus byas stong pa nyid dang /

15. 'dus ma bhas stong pa nyid dang /

16. mtha' las 'das pa stong pa nyid dang /

17. mi dmigs pa stong pa nyid dang /

18. chen po stong pa nyid dang /

19. don dam pa stong pa nyid dang /

20. rang bzhin stong pa nyid dang /

21. rang bzhin med pa stong pa nyid dang /

22. rang gi mtshan nyid stong pa nyid dang /

23. thog ma dang tha ma med pa stong pa nyid dang /

24. dor ba med pa stong pa nyid dang /

25. dngos po med pa stong pa nyid dang /

26. dngos po med pa'i ngo bo nyid stong pa nyid dang /

27. bon thams cad stong pa nyid dang /

28. stong pa nyid stong pa nyid dang /

29. dran pa nye bar bzhag pa bzhi dang /

30. yang dag par spongs pa bzhi dang /

31. rdzu 'phrul gyi rkang pa bzhi dang /

32. dbang po rnams dang /

33. xxx xxx rnams dang /

34. gshen rab kyi lam bzhi dang /

35. mi 'jigs pa'i stobs rnams dang /

36. thar pa'i lam brgyad dang /

['bras bu gsum]

37. phyir mi ldog pa'i 'bras bu dang /

38. lan cig phyir 'ong pa'i 'bras bu dang /

39. rgyun du zhugs pa'i 'bras bu dang /

40. tshad med pa bzhi dang /

41. g.yung drung gis bon phye ba med pa las ma 'dres pa dgu dang /

42. yang dag par rig pa nyid dang /

43. g.yung drung shes pa'i yan lag dgu dang /

44. gshen rab kyi bden pa dang /

45. so so yang dag pa'i rig pa bzhi dang /

46. mi bsnyel ba'i gzungs dang /

47. mthar gyis snyoms par 'dzug pa dgu dang /

48. mtshan ma med pa la snyoms par 'jug pa bzhi dang /

49. rgyun du bzhugs pa'i thugs rje bzhi dang /

['bras bu'i rtags bcu gcig]

50. rtogs pa chen po'i lta ba dang /

51. bsrungs du med pa'i dam tshig dang /

52. lhun gyis grub pa'i phrin las dang /

53. rnam par dag pa'i spyod pa dang /

54. legs par 'byung ba'i yon tan dang / [86]

55. snyoms par gnas pa'i ngang nyid dang /

56. 'gyur ba med pa'i sku dang /

57. rang bzhin med pa'i gsung dang /

58. mnyam nyid 'khrul ba med pa'i thugs dang /

59. rnam pa thams cad mkhyen pa'i ye shes dang /

60. bla na med par yang dag par rdzogs pa'i 'bras bu.

la sogs pa ni mya ngan las 'das pa'i bon te / rnam par byang ba'o // //